A Liberal “Moral Reckoning” Can’t Solve the Problems That Plague Black Americans

If we view the problems of poverty, health care, and criminal justice through a lens that filters out the political-economic underpinnings of these injustices — informed by the language of moral reckoning — we may just end up with modest reforms at best and symbolic gestures at worst, when what we need is fundamental structural change.

Liberals have divorced racial inequality from political economy and have consistently rejected redistributive class-based anti-poverty policies that might address the sources of economic inequality that have, indeed, impacted blacks disproportionately.

This has been a nightmarish year. COVID-19 has afflicted about forty-five million people and killed more than a million across the globe. A month after President Donald Trump finally acknowledged that we were in the throes of a pandemic, some eighteen million American workers lost their jobs. While that number has since fallen to thirteen million, economic uncertainty is the new normal.

Although a Joe Biden victory would mean that working people will surely lose less ground than under a second Trump term, they are unlikely to make any substantive gains, either — hobbled by the commitment of the Democrats to neoliberalism, not to mention Trump’s three US Supreme Court and more than two hundred federal court appointments.

There are many dissatisfying things about where we are today. But even as I can accept the view that the best we can hope for in the coming weeks is Biden-Harris’s promised reprieve from Trumpism’s animus-fueled chaos, I remain dismayed by the ubiquitous calls for a “reckoning” or a “collective healing” that have completely dominated discourse on racial inequality in the months since George Floyd’s murder. While I’m sure decent people derive comfort from such phrases, this brand of moralism masks a class politics that offers poor and working-class black and brown people symbolic rather than material rewards.

The Sanders Opening

Our predicament today is obviously far worse than four years ago. But the bleakness of the moment derives not simply from the human tragedies and uncertainties around us. In fact, despite Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton, 2016 offered progressives cause for hope about the future, thanks to the surprising resonance of the Bernie Sanders campaign with voters across partisan lines.

Forty-three percent of Democratic primary voters in 2016 responded to Sanders’s calls for free higher education, national health care, regulation of Wall Street, and policies intended to encourage the downward redistribution of wealth. This showed that a quarter-century of bipartisan neoliberal policies — which have widened the divide between the rich and everyone else — had not eliminated the potential for a mass egalitarian politics in the United States.

Although Sanders’s 2020 primary performance was less impressive, the Sanders campaign’s imprint on the Democratic electorate — shaped, in no small part, by the unambiguous precarity of Generation Z and millennials — was transparent. At the start of the 2020 Democratic primaries, poll after poll showed a clear majority of Democratic voters, especially those under sixty-five, supported Medicare for All, tuition-free public higher education, and increasing the US minimum wage to a living wage — Sanders’s signature platform issues.

As a result, nearly all of the 2020 Democratic hopefuls declared their support for raising the minimum wage, improving collective bargaining rights, and making college more affordable. And while unabashed centrist Democratic hopefuls like Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and Joe Biden remained ardently opposed to Medicare for All, the popularity of this issue with voters across partisan lines compelled even figures like Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren to embrace national health insurance — at least for a time.

Deflecting Class Politics

If, prior to summer 2020, the impact of Bernie Sanders on Democratic discourse was cause for optimism, the efficacy with which centrist Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden used identity politics to dispatch Sanders was cause for alarm. Attacking Sanders from the right via rhetorically left, identity politics frameworks, centrist Democrats, and even some progressives, identified his platform as an anachronistic class agenda that deflected attention from white racism and its consequences for blacks.

In 2016, for example, Hillary Clinton asserted that Sanders’s calls for stronger banking regulations would not address the “systemic racism” that hobbled so many black homeowners — a narrative that shifted attention from Bill Clinton’s complicity in the subprime mortgage crisis through deregulation of the banking industry. Falling back on a human-resources–friendly update of “the Devil made me do it” defense, Secretary Clinton likewise asserted that the “implicit bias” we all share explained her firm embrace of tough-on-crime politics and racist constructs like “super-predators” during the 1990s.

In 2020, Vice President Joe Biden — harmonizing with a narrative advanced by Representative James Clyburn and the Congressional Black Caucus — questioned the commitment of Bernie Sanders to the “black community” by, among other things, characterizing Medicare for All as an attempt to erase the legacy of the nation’s first black president.

Since the conclusion of the Democratic primaries, discourse on racial inequality has circled the drain of a maudlin anti-racist discourse centered on racial reckonings for the nation’s original sin of slavery. If Robin DiAngelo and Ibram Kendi are the most visible apostles in the moral crusade against racism, public intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates is the movement’s prophet in chief. Blending rhetorical militancy with moralistic purple pleading, Coates’s 2014 “The Case for Reparations” soft-pedaled the demand for reparations to an audience disillusioned with President Obama’s post-racial presidency and frustrated by lingering disparities in wealth and the criminal justice system.

Reparations Go Mainstream

Coates’s popularity notwithstanding, prior to 2016, the call for reparations was still confined to particular academic circles and the talk show circuit. Two developments created space for reparations to seep into policy discourse.

First, the popularity of the Sanders platform revealed mass disaffection with the complicity of the Democrats in the Reagan Revolution. Secondly, Donald Trump’s surprise victory over Hillary Clinton, likewise, revealed widening cleavages within the Democratic Party, since the win was made possible by a combination of depressed Democratic turnout and Trump flipping a sufficient number of Obama voters in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

In the wake of Clinton’s defeat, Coates’s “The Case for Reparations,” along with its many sequels, provided the Democratic Party of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama with convenient cover for the damage it inflicted on working-class Americans — white and black alike. Specifically, Coates’s insistence that the voters Trump had flipped were motivated, in no small part, by a desire to erase the legacy of the nation’s first (neoliberal) black president, complemented the DNC’s self-serving election postmortem.

Indeed, Coates and the DNC either ignored or downplayed the disaffection engendered among unionized blue-collar voters by Obama’s decision to rescind his support for the Employee Free Choice Act; Obama’s active support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership; and his means-tested, Heritage Foundation–inspired Affordable Care Act with its tax on nonprofit union health plans, which — had this provision been implemented — would have been bankrupted to subsidize private, for-profit health insurance. By attributing Trump’s victory to the “bloody heirloom” of white supremacy, then, the accounts offered by Coates and the DNC obscured the electoral consequences of the neoliberal policies pursued by Obama and the Clintons — policies that did real damage to an important segment of Democratic voters.

The Flaws of American Liberalism

Although Coates ultimately voted for Sanders in 2016, his attacks on the calls made by Sanders for universal and redistributive programs aided and abetted a rightward attack on the kind of class-based policies from which the masses of working-class and poor blacks and Hispanics would disproportionately benefit. Since African Americans are, indeed, overrepresented among the nation’s poor and working class, blacks would have benefited disproportionately from Medicare for All, living wage polices, tuition-free public higher education, and a more robust public sector.

To be clear, I doubt neither Coates’s sincerity nor his good intentions. However, his reparations advocacy rests upon a basic mischaracterization of the inadequacies of American liberalism, and that his project — steeped as it is in moralism — is an unwitting call to continue along much the same path that has failed poor and working-class blacks since the 1960s.

There is no doubt that postwar liberal orthodoxies failed to redress racial disparities. The culprit, however, is not the sway of a metaphysical racism, as Coates argues. Rather, the roots of contemporary disparities can be traced to far more comprehensible forces, including: the tensions within the New Deal between the regulatory and compensatory state models and the related mid-century tensions between industrial and commercial Keynesians; the contrasting influences of the New Deal and the Cold War on the parameters of liberal discourse about race and inequality; and neoliberalism’s rise from the ashes of the Keynesian consensus.

In other words, the failure of postwar and contemporary liberalism is not, as Coates insists, because liberals have long attempted to redress black poverty by reducing racism to class exploitation, resulting in universal policies that focus on economic sources of inequality as an alternative to addressing racism. The problem is that liberals have divorced racial inequality from political economy.

In fact, liberals have consistently rejected redistributive class-based anti-poverty policies that might address the sources of economic inequality that have, indeed, impacted blacks disproportionately.

Informed by culturalist constructs like ethnic pluralism, the culture of poverty, and underclass ideology, liberal policymakers since the 1960s have generally downplayed or even ignored the disproportionate impact on African Americans of issues such as deindustrialization, the decline of the union movement, and the retreat of the public sector. In the 1960s and ’70s, the consequences of this disposition were not so terrible, since the postwar consensus remained in place, causing liberals to pursue anti-poverty policies centered on the expansion of social services and even state-centered regulation of labor relations via affirmative action.

However, the breakdown of that consensus and the rise of neoliberalism ensured that Democratic presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama would follow the lead of their Republican counterparts, chipping away at the rights and protections that disproportionately benefitted black Americans, at the very same time as they championed (or personified) diversity.

Running to Stand Still

To say that postwar and contemporary liberalism have not served most black Americans well is not to deny the historic importance of — or the current need for — antidiscrimination policies. Antidiscrimination legislation such as the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and policies like affirmative action helped improve the lives of many black Americans — my parents and myself among them, just as my grandparents benefited from the GI Bill and New Deal programs.

Nevertheless, policies like these have failed to eliminate disparities because earning power for all but the top wage earners has been on a fifty-year decline. As I pointed out in a previous essay, between 1968 and 2016, median black household income increased from the twenty-fifth percentile to the thirty-fifth percentile. Over the same period, median white household income moved from the fifty-fourth to the fifty-seventh percentile. However, despite the relative gains that blacks have made with the aid of antidiscrimination policies, the wage and wealth gap has scarcely budged since 1968. Automation, the slow death of the union movement, and public-sector retrenchment have contributed to a decline in real income for the bottom 80 percent of American workers.

The good news is that the relative gains blacks have made since 1968 have prevented the racial income gap from worsening. In fact, had African Americans not made any relative progress over the past fifty years, the ratio of median black to white household income would have fallen from 57 percent to 44 percent. The bad news is that the black-white family income ratio would have risen from 57 percent to 70 percent if overall wages had remained constant over the past fifty years.

The call for “universal” programs such as Medicare for All and redistributive class-based reforms — like the Fight for $15, a more robust public sector, a stronger union movement, free public higher education, etc. — is not a denial of the existence of racism. Nor is it an argument for eliminating antidiscrimination policies. But if we don’t view racial disparities through the lens of American political economy, we will not only fail to redress income inequality — we will also fail to eliminate black poverty.

Healing the American Psyche

This concern is, of course, at the heart of the problem with Coates’s analysis, which mischaracterizes the root causes of the failures of liberalism. Worse yet, the author’s moralizing and frequent use of metaphor as an alternative to analysis makes it possible to sidestep solutions. Consider the following passage from “The Case for Reparations” on the utility of HR 40:

Perhaps after a serious discussion and debate — the kind that HR 40 proposes — we may find that the country can never fully repay African Americans. But we stand to discover much about ourselves in such a discussion — and that is perhaps what scares us.

Insinuating that the exercise alone has the potential to check racism’s eternal sway, he continues:

The recovering alcoholic may well have to live with his illness the rest of his life. But at least he is not living a drunken lie. . . . What is needed is an airing of family secrets, a settling with old ghosts. What is needed is a healing of the American psyche and the banishment of white guilt.

The moralistic pitch of “The Case for Reparations,” combined with Coates’s fuzziness on the difference between anything reasonably understood as reparations on the one hand and torts or charity on the other, led me to the following conclusion in March 2018:

Whereas President Obama’s soaring post-racialism licensed the continuation of liberal indifference to the plight of economically marginal people via underclass metaphors, Coates’s post-post-racial commitment to racial ontology signs off on white liberal hand-wringing and public displays of guilt as alternatives to practicable solutions to disparities. To be sure, this is not Coates’s formal intent, even if the words on the page imply that Coates might find a racial Festivus to be an acceptable alternative to material compensation. But because reparations is a political dead end, Coates is offering white liberals — and even a stratum of conservatives — who are either self-consciously or reflexively committed to neoliberal orthodoxies absolution via public testimony to their privilege and their so-called racial sins.

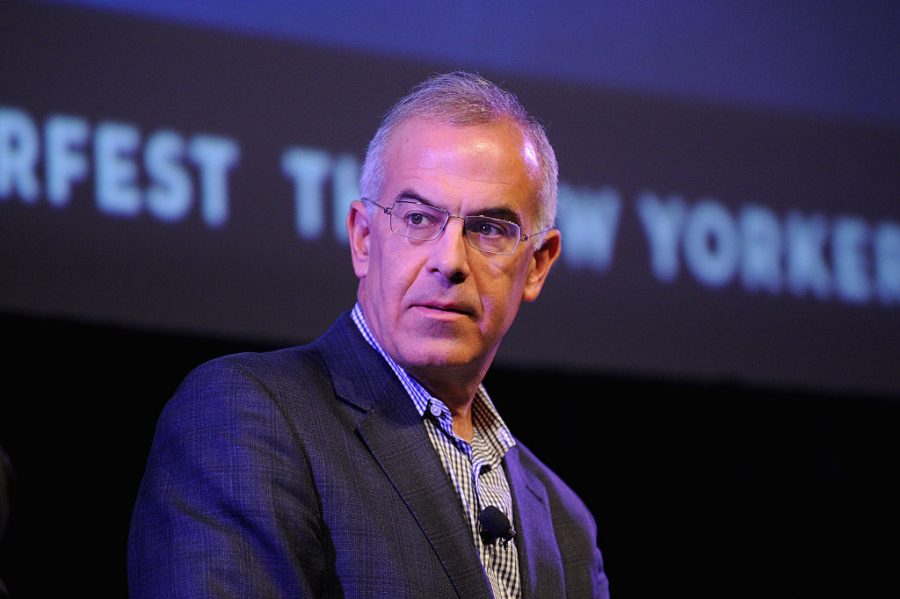

The volte-face of conservative columnist David Brooks on reparations is a good example of the issue that I pointed to. Over the past couple of years, Brooks has moved from being a Coates fan who dismissed reparations but appreciated Coates’s explorations of “black rage,” to a self-identified supporter of reparations — at least as a brand.

David Brooks Imagines a New America

In his March 2019 New York Times op-ed, “The Case for Reparations,” Brooks spoke of the necessity of reparations to mend a “racial divide born out of [the] sin” of slavery. According to Brooks, bondage did not inflict injury solely upon the slaves themselves: slavery’s corrupting influence over our “whole society” can still be felt today.

Brooks insisted that the time for a “racial reckoning” and the payment of a “collective debt” is now. Nevertheless, he still rejected the idea of reparations in the form of a direct cash payments — and did so by quoting the following passage from Coates:

And so we must imagine a new country. Reparations — by which I mean the full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences — is the price we must pay to see ourselves squarely . . . What I’m talking about is more than recompense for past injustice — more than a handout, a payoff, hush money, or a reluctant bribe. What I’m talking about is a national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal.

A year later, Brooks elaborated on his vision of reparations in another New York Times op-ed, “How to Do Reparations Right.” For Brooks, reparations “would involve an official apology for centuries of slavery and discrimination and spending to reduce their effects.” The practicable solutions Brooks advocates center on grants to community leaders — people who have the clearest window onto their communities’ needs.

The conservative columnist acknowledges that his proposal sounds quite like the failed Community Action Programs (CAP) of the War on Poverty, but asserts that CAP failed because it funded disruptive agitators who stirred up conflict between local activists and elected officials. Brooks, by contrast, envisions funding channeled to responsible community leaders only — whatever that means.

Of course, CAP was ultimately doomed to failure because the Johnson administration paid little heed to the disproportionate effects of deindustrialization on blacks and other low-skilled workers. Its anti-poverty agenda eschewed direct job creation in favor of antidiscrimination legislation, cultural tutelage for the black underclass, and tax cuts intended to stimulate economic growth — all of which Brooks has endorsed as well.

Symbols Over Substance

Since the 2016 Democratic primaries and the breakthrough of the Sanders campaign, topics that had long been dismissed as pie in the sky have become part of regular discourse. The brutal murders of men and women who are disproportionately black or brown, caught on video, have helped galvanize calls for criminal justice reform.

But if we view the problems of poverty, health care, and criminal justice through a lens that filters out the political-economic underpinnings of these injustices — informed by the language of moral reckoning — we may just end up with modest reforms at best and symbolic gestures at worst, when what we need is fundamental structural change.

Indeed, the weeks immediately following the police murder of George Floyd by Derek Chauvin opened the floodgates for public displays of racial guilt and penance. Aunt Jemima announced it was changing its brand name, finally acknowledging — as the chief marketing officer of Quaker Foods, Kristin Kroepfl, put it — that it was “based on a racial stereotype.”

Hundreds of whites in George Floyd’s hometown kneeled to ask “the black community” for their forgiveness, as efforts to remove the many monuments to treasonous defenders of slavery that mar the Southern landscape gathered pace. Chick-fil-A’s conservative Christian CEO, Dan Cathy, called on his fellow parishioners at Atlanta’s Passion City Church to repent and fight for black Americans. And about a dozen corporations — with several former American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) members among them — set aside nearly $2 billion for anti-racist initiatives.

To be sure, the moment of “racial reckoning” that lies before us has produced rhetorical interest in reparations among policymakers. Still, Democratic politicians who have insisted on both the righteousness and rightness of reparations — ranging from progressive Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren to Newark mayor Ras Baraka — have merely rebranded means-tested and trickle-down policies as “reparations.” In much the same way as David Brooks, Warren, Baraka, and Joe Biden have advocated solutions that sound like a cross between the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty and Nixon’s black capitalism.

Human tragedy abounds in this moment, from police violence to COVID-19, and it is good that people are alive to some of the many problems that plague us now. But we need to reason our way out of the misery before us, rather than simply “feel” our way through this quagmire. We need to think about the kinds of coalitions our conceptual frameworks will help us forge, and whether those frameworks and coalitions will bring us to our desired ends.

The fact that former ALEC affiliates can “embrace” constructs like “moral reckonings” and “systemic racism” tells us something vital about where this road will take us. ALEC has drafted model legislation calling for the privatization of public schools and universities, as well as bills that have sought to erode environmental regulations, worker safety, and the right to collective bargaining. ALEC also drafted the model legislation that gave us Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” laws — which contributed to the murder of Trayvon Martin and ultimately led to the acquittal of George Zimmerman — along with similar legislation in many other states.

What kind of democracy do we want to live in? Do we want to live in a democracy where 13 percent of each class layer — rich, middle class, poor — are black, while 90 percent of the population struggles to make ends meet? Or do we want to live in the kind of democracy where no one has to suffer the nagging misery of despair and vulnerability because of stark material inequities?