What Is Class-Struggle Unionism?

We really, really need unions. But not all unionism is created equal. We need unions that are willing to fight the bosses rather than cozy up to them. We need class-struggle unionism.

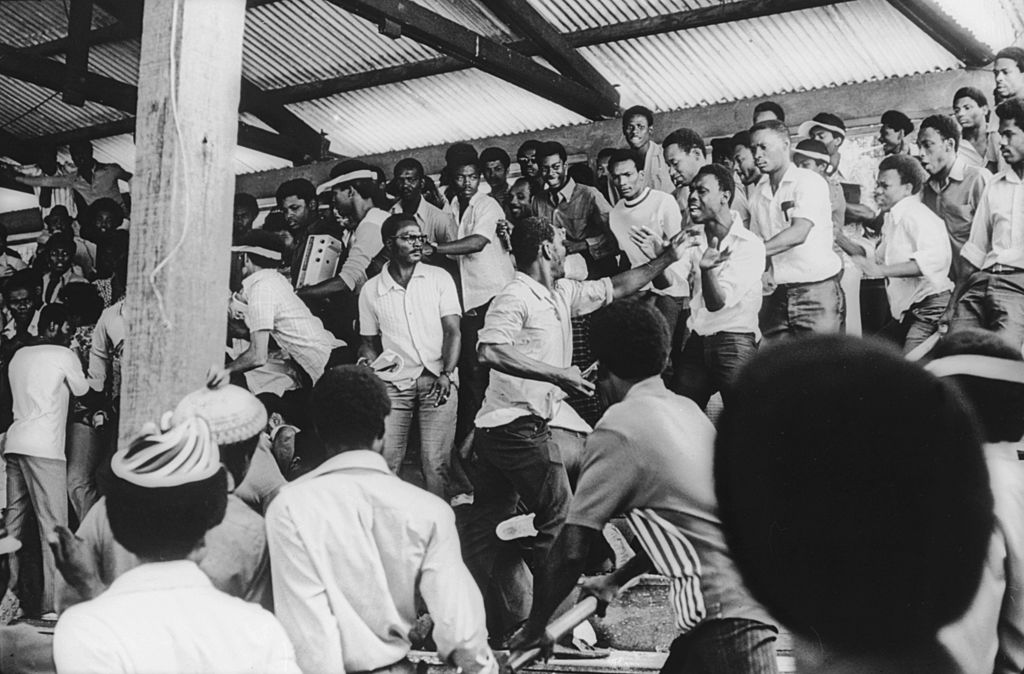

At the Electric Auto-Lite plant in Toledo, Ohio, on May 26, 1934, strikers reject a peace proposal amid scenes of violence when a National Guard and a civilian were wounded. The successful Toledo strike was one of the key labor battles of the 1930s. (New York Times Co. / Getty Images)

It can’t be said enough times: to build a better world, we must rebuild the labor movement. But it’s not enough to just organize unions; we also need unions that fight the boss rather than cozy up to them. We need class-struggle unionism.

Class-struggle unionism is based on a very simple concept: that workers create all wealth in society through their labor, but their bosses steal that wealth from workers and sock it away for their own benefit, rather than the benefit of the workers themselves. That is how and why we have billionaires in society. To take back that wealth and all the power that comes with it, we need unions that are willing to go toe-to-toe with those bosses.

In contrast to the strategy of business unionism, which seeks to represent the interests of narrow groups of workers at an employer or industry and fights for “a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work,” class-struggle unionists believe that there’s no such thing as a truly fair wage under a system in which bosses steal from workers all day long. Those workers create all wealth, and our union struggles are part of a larger fight between labor and the billionaire or owning class.

This orientation leads to a distinctive form of unionism that prioritizes demands for all workers, not just union members in one particular workplace or industry, which means fighting against racism and sexism both on the job and in the society. But it also meant a very distinctive union set of ideas and practices. One of the key elements of that is the understanding that unions and employers are locked into constant battle, which leads to class-struggle unionism.

Class struggle unionists, rather than seeing our worker-owner relationship as primarily cooperative but with occasional flare-ups, recognize that conflict is baked into an economic system that pits the interests of the working class against the employing class. This leads class-struggle unionists to create a combative form of unionism that places sharp demands on employers and promotes rank-and-file worker activism.

Them and Us

There’s a long history of class-struggle unionism in the United States.

Under its left-wing leadership, Teamsters Local 574 conducted one of the most militant general strikes in US history, the 1934 Minneapolis truckers’ strike. During this strike, truck drivers in Minneapolis fought the police, shut the entire city down, and won unionization for hundreds of workers. Local 574 went on to spur unionization of truck drivers in the upper Midwest.

On the heels of the 1934 Minneapolis truckers’ strike, the class-struggle militants wrote a new preamble to the Local 574 bylaws:

The working class whose life depends on the sale of labor and the employing class who live upon the labor of others, confront each other on the industrial field contending for the wealth created by those who toil. The drive for profit dominates the bosses’ life. Low wages, long hours, the speed-up are weapons in the hands of the employer under the wage system. It is the natural right of all labor to own and enjoy the wealth created by it.

This one short paragraph contains many of the concepts of class-struggle unionism. It reflects a core value of class struggle unionism — the idea that labor and capital are locked in a battle, confronting each other on the industrial field. But it also contends that we are fighting to retain “wealth created by those who toil.” This framework sets up an inescapable battle between those who exploit and those who produce. And the preamble ties in the direct workplace concerns of the workers with the relentless greed of employers — another distinguishing characteristic of class-struggle unionism.

Similarly, Big Bill Haywood’s speech at the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) proclaimed:

This organization will be formed, based and founded on the class struggle, having in view no compromise and no surrender, and but one object and one purpose and that is to bring the workers of this country into the possession of the full value of the product of their toil.

Whereas class-struggle unionists promote class struggle, business unionists seek to avoid it. Business unionists value their relationship with management, often identify with company concerns, and consider themselves more pragmatic than the workers. That’s not to say they won’t struggle or get into bitter strikes, but overall they tend to view these as fights against unreasonable employers.

Class-struggle unionists don’t think this way. We think more in the vein of the title of the classic labor book Them and Us: Struggles of a Rank-and-File Union by United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) activists James J. Matles and James Higgins. The book chronicles the UE’s journey as a class-struggle union, formed in the battles of the 1930s.

UE was one of the eleven left-led unions that after World War II came into conflict with the government, corporate America, and business unionism. Fiercely democratic and contesting management at every turn, UE offers a different brand of organization even today. Them and Us captures the essence of UE’s brand of class-struggle unionism. Core to UE’s belief, and indeed to all class-struggle unionists, is the idea that we are locked in relentless battle with employers.

Rejecting Collaboration With the Bosses

Understanding that our unionism is a struggle between workers and owners should be considered the cardinal principle of class-struggle unionism. It is a simple idea that provides quite practical advice to guide our labor work:

- Understand that powerful financial interests are lined up against our unions.

- Understand that agreements with employers are temporary truces rather than alignment of interests.

- Understand that we have opposing interests on every issue.

- See ours as a struggle between classes.

The concept of us versus them is at the core of class-struggle unionism.

In contrast, business unionists see workers’ interests as aligned with those of employers. Having accepted the narrow framework of the wage transaction, business unionists tie the fate of workers to the success or failure of the firms they work for. Rather than believing labor creates all wealth, they accept the general framework that the employer controls the workplace and the fruits of labor. This forces us to negotiate from a position of weakness against an employing class that is constantly amassing greater power.

Business unionists often see workers they represent as unreasonable and themselves as the realists. They seek a softening of struggle, they seek accommodation with owners, and they hate the unrestrained worker self-determination of open-ended strikes. Seeing their unionism not as class struggle but narrowly defined against particular employers, they often believe their role is merely to protect their members from rogue employers, rather than to fight for the entire class. This frequently leads to an exclusionary and often racist unionism that ignores the rest of the working class and sees immigrants and workers around the world as enemies rather than allies.

At the core of business unionism is class collaboration, which means these unionists see their interests more allied with management and owners than with other workers. Rather than seeing bosses as exploitative and our natural enemies, they see the unions as allies of management. This leads business unions to see workers at a plant they represent as being in competition with workers at other plants rather than sharing common interests; or construction unions fighting for construction jobs to build a Walmart store while ignoring the effect of such an anti-union employer on the rest of the working class.

At a broader level, they often identify workers from other countries as the problem. For example, in the early 1980s the US auto industry was under competitive pressure from Toyota and other automakers. Even though this was the same time auto management, like other industries, was launching an anti-union offensive, the United Auto Workers chose to attack foreign workers.

For unionists this idea should be simple — labor and management have opposing interests. However, powerful forces in society constantly work to undermine this key principle. Government mediators and some university labor educators like to promote what they call win-win bargaining, labor-management cooperation programs, or interest-based bargaining. These concepts all share the view that labor and management share common interests and we just need to figure out how to get to a mutual “yes.”

But we know this cannot be true. On every issue in bargaining, labor and management have opposing interests. When bargaining wages, the billionaires will get a greater share of the wealth that labor produces, or the workers will. In shop-floor struggles, workers will work harder and be more exhausted at the end of the shift, or work less. On safety, we want better equipment, and they want to pinch pennies. Labor’s gain is management’s loss.

Despite this, many union officials support various labor cooperation schemes promoted by management. Sometimes management does this when unions are powerful to lull the unions to sleep. But often they will employ this strategy during periods of relative weakness when they know business unionists will jump at the chance.

For the first couple of decades of the twentieth century, the labor movement was engaged in pitched battles with employers. While many of us have heard of the classic battles of the IWW, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions also fought for unionization. In certain industries such as streetcars and mining, labor battles looked like armed warfare. Employers relentlessly attacked unions and declared that entire industries would operate on a nonunion, open-shop basis.

Yet despite all of this, the leadership of the AFL struck up a partnership with the National Civic Federation (NCF). The NCF was led by industrialist Mark Hanna, with AFL leader Samuel Gompers as vice president. The group preached harmony among classes and labor peace, largely on capital’s terms. Although management and labor supposedly came in as equals, Hanna referred to AFL leaders such as Gompers as his lieutenants.

During the 1920s, there were two paths forward for the labor movement. As noted labor historian Philip Foner pointed out, “Convinced they could not win out against the large employers, the AFL leaders pushed the idea that union-management cooperation had to replace labor militancy as the only way to maintain the existence of unions.” William Z. Foster explained in his 1927 book Misleaders of Labor that class collaboration was deeply rooted in AFL business-unionism philosophy:

Between the working class and the capitalist class there rages an inevitable conflict over the division of the products of the workers’ labor. . . . The theory of class collaboration denies this basic class struggle. It is built around the false notion of a fundamental harmony of interests between the exploited workers and the exploiting capitalists.

This allowed employers to form alliances with the business union leaders to buy them off.

While Gompers and other AFL officials were being wined and dined, the legendary Mother Jones traveled around wherever workers were struggling. As she testified, “I live in the United States, but I do not know exactly where. My address is wherever there is a fight against oppression.” Indeed her autobiography reads of constant struggle and much sorrow. Now, we are not all going to be Mother Jones, but we can have a similar approach to building struggle.

Likewise, union militants affiliated with the Communist Party waged bitter strikes in Southern textile mills, engaged in early auto industry strikes, and built the mining wars of West Virginia and southern Illinois. Although they lost more than they won, these efforts paved the way for the 1930s upsurge.

Which Side Are You On?

Later generations of class-struggle unionists adopted this approach. During the 1980s and early 1990s, many labor officials fell for labor-management cooperation programs rather than fighting. Unions such as the United Auto Workers and many others worked jointly with management to speed up the pace of work.

The group Labor Notes contributed to developing an ideological pole against these jointness programs, publishing books such as Concessions and How to Beat Them and several that critique the jointness programs, in which unions partnered with management to operate “more efficiently” so as to better compete with other facilities. In practice this meant the unions got in bed with the company to make workers work harder.

Class-struggle unionists coalesced around a different course for the labor movement centered on labor solidarity, strike support, resistance to labor-management cooperation, and worker internationalism. Central to left-wing trade unionism in the 1970s and 1980s was fighting against what these unionists saw as “sellout” union officials. Meatpackers, autoworkers, transit workers, steelworkers, truck drivers, and mineworkers all saw significant reform movements explicitly offering member control and militancy as an alternative path forward for labor.

During the 1980s and 1990s, a vibrant left wing of the labor movement saw militancy as key to reviving labor. In key battles, activists sought to push free from the restrictions in labor law. During the Hormel strike in the mid-1980s, a militant local union sought to break free from the restrictions on solidarity. United Food and Commercial Workers Local P-9 set up picket lines at other plants in the system, argued that fighting concessions was the only way forward for meatpackers, and came into sharp conflict with their national union.

In many other situations, striking local unions who sought to fight back conflicted with their international unions, which favored collaboration. These battles — including paperworkers in Jay, Maine, A.E. Staley workers in the mid-1990s, and Detroit News workers — were flashpoints drawing together militant supporters from across the country.

The strikes took on an oppositional tone. The Staley workers picketed the 1995 AFL Executive Board meeting, demanding that the AFL leadership back their strikes. This form of unionism drew sharp lines between workers and employers, engaged in fierce battles, and frequently came into conflict with union leadership.

You can tell who the class-struggle unionists are by how much they fight the boss and the intensity of the struggle. When the chips are down, and the workers are fighting the boss, do they try to calm things down, or do they join in the struggle and seek to intensify it?