“When You Arrest as Many People as We Do, You Cannot Protect Against Infectious Spread”

A new study finds that American jails — not just prisons — are a major hot spot for spreading coronavirus. The solution is simple: stop arresting so many people.

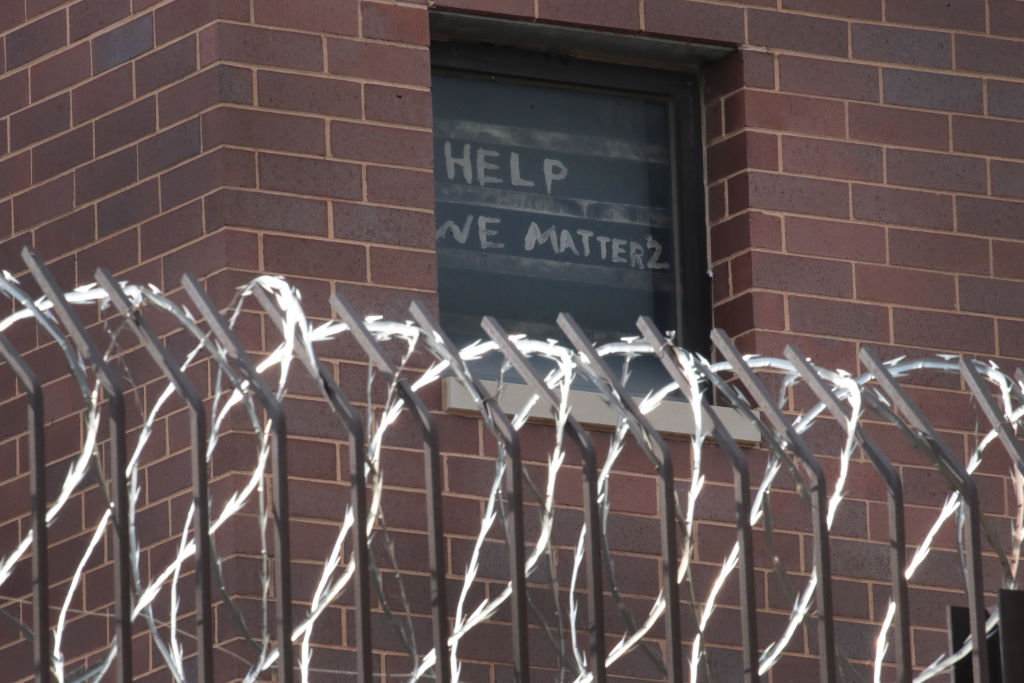

A sign pleading for help hangs in a window at the Cook County jail complex on April 9, 2020 in Chicago, Illinois. (Scott Olson / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Doug Henwood

The role of prisons in COVID-19 hot spots is fairly well known. Less known, however, is the role of jails. Prisons are places where people are held after conviction for a major crime; jails are where people are caged after arrest and while awaiting trial.

Eric Reinhart, an anthropologist, and Daniel Chen, an economist, have a paper in Health Affairs that estimates how jail turnover has fostered the spread of COVID-19 in Chicago. Reinhart and Chen find that one in six cases of coronavirus in the city can be traced to the Cook County Jail. The role of the jail in spreading the disease also helps explain the disproportionate effect COVID-19 has had on black people in the United States, who are, of course, disproportionately incarcerated.

Doug Henwood, the host of Jacobin Radio’s Behind the News, recently interviewed Reinhart on his program. The following is a condensed version of their conversation; you can find the entire audio here and subscribe to Jacobin Radio here.

We’re all aware of the count of two million people behind bars in this country, but less well known is how many people get arrested and spend some time in jail. How many people are we talking about who experience that?

About five million people nationally cycle through jails every year. Roughly 42 percent of them, according to an American Economic Review study that looks specifically at Philadelphia County and Miami-Dade County, will be proven innocent. And 95 percent nationally are taken to jail for nonviolent offenses — most of them for petty alleged crimes.

Conservatives say that public safety requires locking up all these people. What do you say to that?

There’s a Brennan Center study that shows for about 40 percent of the prison population — so these are people who have been convicted of crimes — there is no compelling public safety reason for them to be locked up. When you’re talking about the jail population, like I said, 42 percent, roughly, are going to be proven innocent. The vast, vast majority are in there for nonviolent offenses.

These are not serial killers. These are homeless people who pee on the street because they don’t have a place to go to the bathroom. These are people like George Floyd, for example, who is alleged to have passed a counterfeit $20 bill. There are no real public safety reasons to detain these people. There are a lot of ways you can manage these kinds of alleged crimes.

Many of them have to do with structural issues like poverty, lack of adequate housing, lack of food security, lack of a basic income so they can provide for themselves. This produces desperation. Regardless of the cause, there are many, much more effective ways to manage alleged petty crimes.

You can issue citations, you can require community service, you can provide people with mental health referrals, you can provide people with adequate housing and food support. These would be rational responses to the vast majority of the crimes, alleged crimes, for which we arrest and incarcerate people in jails in the United States every year.

Tell us about the paper — who did you study, and what did you find?

Every day in the United States, we arrest twenty-eight thousand people and release a nearly commensurate number back into communities. Most people stay in jail for a matter of days, some only hours. So I was thinking, this has to be implicated in the spread of COVID-19.

I filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office. I got data from the Illinois Department of Public Health and the US Census and American Community Survey. And with that, we had zip code–level data for all of those who were booked and released from Cook County Jail from February 1 to the day they delivered the data, April 19. We’ve since gotten updates. And when we control for all other variables, we find that jail cycling independently accounts for one in six cases in the state of Illinois and in the city of Chicago.

We’re just looking at one jail, Cook County Jail. There are a lot of other jails, and these dynamics that we observed, we expect, are happening in other places. This is not just a problem of internal jail conditions. When you arrest as many people as we do in the United States, and you process them through these facilities, you cannot adequately protect against infectious spread. If only one person with COVID-19 is in that facility, by the end of that processing period, which takes hours typically, many, many people will be infected.

You have to address this at the level of arrest volume. And as you said earlier, there really isn’t a good, compelling public safety reason to arrest the vast majority of these people — and certainly not during the pandemic, when now, by arresting these people, you are infecting communities across America.

We’re now completing a study with county-level data across the country. And we see something very similar. We’re going to submit that this week or next for peer review, but what we see there — well, I can’t give you the exact numbers because it depends on final specifications and things may change somewhat in the peer review process. I don’t want to say anything that’s not going to hold up and remain correct after proper review. But what we see in the data, provisionally, is that for every X number of arrests per day — and it’s not an extraordinarily large number relative to existing standard practices — you undo the effect of social distancing policies.

So if you have stay-at-home orders issued in a locality and you’re arresting X number of people in a particular county, which we are seeing is ranging from an increase of 2 percent to 80 percent over ordinary daily arrest figures, depending on the racial and class composition of the county and Covid dynamics there, the benefit you’ve accrued by issuing the stay-at-home order is undone by the epidemiological implications of jail cycling.

This would go some way toward explaining why the impact of COVID-19 has been disproportionately large in communities of color and communities with high poverty rates, which is often saying the same thing in the United States.

Yes. The racial dimensions here are very big. Depending upon the year, roughly 70 percent to 75 percent of the people who are cycled through Cook County Jail are black. In our study with zip code–level data, I can tell you that 60 percent of the additional COVID-19 cases that are associated with jail cycling are occurring in black-majority zip codes in Chicago. If you look statewide, with obviously very different demographics, it’s still 52 percent of additional cases arising in black-majority zip codes.

So this is a huge racial justice issue. Chicago has a very particular demographic constitution with intense segregation. You have that in some other cities in the United States, though not all of them, but there is a national problem of racial discrimination within our criminal justice system. And we have every reason to believe that translates to a disproportionate burden of this problem being borne by black families and black neighborhoods.

You mentioned that there are other factors you controlled for to isolate the effect of jail cycling. What were those other factors, and how do they stack up?

The four controls that seem most important were: percent of residents in a zip code who identify as black, public transit utilization rate, poverty rate, and population density. Race and poverty are very strongly associated. Independently, jail cycling is more strongly associated. You see the strongest basic correlation with jail cycling as opposed to the others.

So it’d be absolutely wrong to interpret this as, “Oh, this study shows that race and poverty are not significant factors. It’s just jail cycling.” No, they are all working together, and they independently all have an effect.

And as I said earlier, there’s every reason to believe that this is quite representative of other jails, including county jails.

Yeah, this is a huge problem in rural areas, too. Say, there aren’t many cases in your area, but you have social distancing put in place, you have stay-at-home orders put in place. There are now suddenly not so many venues in which there’s a risk of mass spread. The one that remains undisturbed is jail processing and jail internal conditions. So it seems that this effect is even stronger in rural areas — this is what our preliminary data analysis shows.

My thought there is that it might have a seeding effect. So you have nobody that’s positive in the jail, but then one day you get one person, and he or she is processed along with sixty other people or forty other people in this rural jail. The rest of them are now very likely to be infected. They’re released within days. Nobody knows they’re infected, and they go back to their communities.

So this is not just an urban issue. It’s not just an issue of large cities. This is a problem of jails across the country.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board took your work and did something very perverse with it. What’d they do?

It’s hard for me to imagine that the Wall Street Journal editorial board does not know the difference between jails and prisons. But in their lead, they say that “released criminals may be spreading the virus.”

This is a scare tactic, because the early response was to say, there are a lot of people in prisons nationally who are at high risk for very severe cases, and they don’t pose a public safety threat. We should release them out of compassionate concerns. We should accelerate releases for those who would have been released shortly, anyway.

They’re trying to instrumentalize our study against those early release policies, when we quite clearly state that we believe these are very important measures but they’re not adequate measures. We also have to address arrests and jailing. So their whole premise began from a conflation of pretrial detainees with criminals. These people are not criminals.

I’m sure the attitude, though, is if they’re arrested, they’re guilty.

Yeah. I think when 75 percent of those arrested at Cook County Jail are black — despite the fact that 42 percent of them are going to be proven innocent — you have to think there’s some kind of a racial sacrificial logic that seems to be operating there. Maybe that’s too strong an accusation, but it’s hard for me to ignore the way in which the writers of that editorial are very ready to sacrifice people of color, because what they advocate for is just keeping all these people locked up permanently to protect everybody else.

One, that won’t work, two, that’s unconstitutional, three, there are many people who are in jails because of issues related to poverty, homelessness, and racism in policing. The proper response and ethical response, a legal response and effective public health response, does not consist of just sacrificing them by having them all die in jails.

We need to address this on a large policy level now. Not at the level of one jail, one sheriff, even one municipality. This has to be done at a massive level. So I’m still trying to get attention to this study at higher levels, where people might have the power to do that. And obviously, even that attention, if I were to get it, is still not enough. You have to have mass collective action that demands that these changes be implemented.

It’s odd to see all these people worrying publicly about all the protesters, who are outdoors and very often masked, spreading disease but not much concern about what happens to all those who got arrested.

Yeah, it’s a huge problem. There have been some places that have decided they’re not going to prosecute. Great, but you should not be arresting these people. You arrest them, you put them in crowded transit vehicles. You make them wait at jails for hours to be processed. You’re exposing them to infection. They go back to their communities, and they’re infecting other people unbeknownst to themselves.

I do suspect that the protests will coincide with something of a surge in cases. But I don’t think it’s going to be because of the protests themselves, but rather the police management of it. As you said, when people are outdoors, masked, the risk of transmission is quite low. The real risk is when you put people in confined spaces, in crowds with stagnant air. So, we’ll see how this bears out, but I have my suspicions as to the direction it’s going to go.