The Appeal and Limits of Andrea Dworkin

Reading Andrea Dworkin today is still bracing. But her pessimistic, dystopian vision of a world dominated by male violence only gained currency when the utopian power of the feminist movement receded.

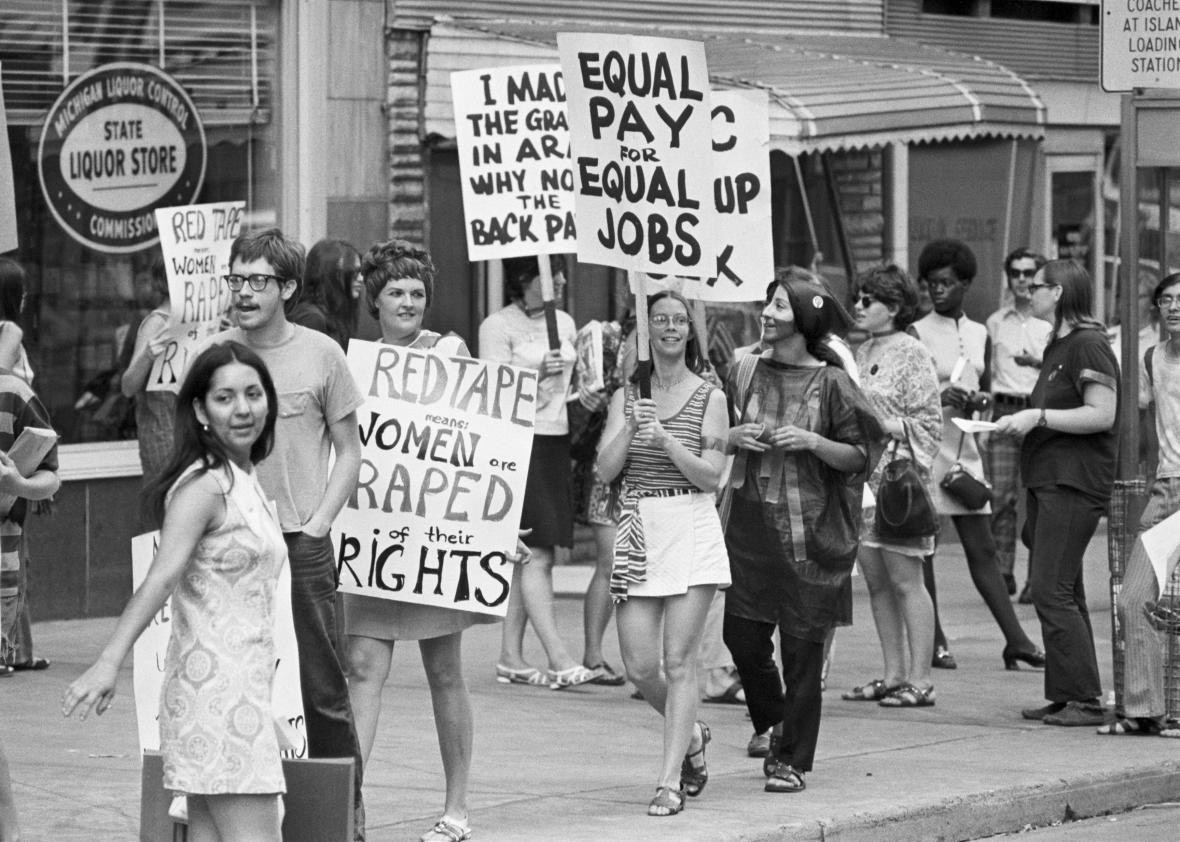

Women’s Liberation Coalition March in Detroit on August 26, 1970. (Getty Images)

Between 1968 and 1972, the radical feminist movement broke through across US culture and politics, engaging in a whirlwind of direct actions, commanding attention that frightened the powers that be, and winning a series of improbable victories. Women picketed targets ranging from universities to the floor of the stock exchange, from the New York bridal fair and Miss America pageant to the office of the Ladies Home Journal and legislative hearings about abortion. Radical and even eccentric books like Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex and Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics became unlikely best sellers, and hundreds of small newspapers, newsletters, and pamphlets helped spread ideas unheard of just a few years earlier.

By her own account, Andrea Dworkin, who died in 2005 and who has received fresh attention following the publication of the collection Last Days at Hot Slit, spent these heady years largely in desperate isolation. By the time Woman Hating, her first nonfiction book, came out in 1974, the wave of early victories and organizing had receded.

Not coincidentally, Dworkin’s influence grew as the backlash against feminism took hold in the eighties, when the utopian visions of the whirlwind period lost their persuasive power. Her dystopian vision of a women’s experience dominated at all times by male violence, or the fear of it, could feel like a bold stance against feel-good corporate feminism, especially in the absence of a dynamic left.

The writer Susie Bright, who opposed Dworkin’s general view of sexuality but who had experienced the power of her writing, would remember after Dworkin’s death:

“It was Andrea’s take-no-prisoners attitude toward patriarchy that I always liked the best. Bourgeois feminists were so BORING. They wanted to keep their maiden name and have it listed in the white pages; they wanted to get a nice corner office in the skyscraper. When I was a teenager in the ’70s I couldn’t relate to those concerns. It was Dworkin’s heyday.”

Dworkin was equally unavoidable for those of us coming up a little later in the eighties and nineties as feminist advances were rolled back and AIDS seemed to make a mockery of the sexual revolution’s utopian vision. We might not have had a dynamic movement, but in Dworkin, many found intellectual daring, the will to critique what had been outside criticism. The dystopian world of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Dworkin’s own novel, Mercy, served as the lyrical companions to Susan Faludi’s Backlash: lamentations for how much had been lost and how much had never been won. If you were young and suspicious of the official proclamations that entering the workplace had given women everything they needed, Dworkin’s insistence that the culture hated you as much as ever could feel something like truth. In the Trump era, when power’s masks are being ripped off daily to reveal the cruelty that was always there, such an appeal is easy to understand.

Particularly prescient, and often ignored in reconsiderations of her work, was Dworkin’s analysis of the Right and its appeal to women — perhaps including herself — in Right Wing Women, written in the early years of the Reagan administration. Dworkin showed how conservative women, far from denying, ignoring, or even embracing sexism, made what often looked like rational trade-offs: in exchange for the promise of what she termed “enforceable restraints on male aggression,” women received relative degrees of safety, economic security, and respect. Dworkin also offered an indictment, highly relevant today, of liberal feminism and its unwillingness to view the women it failed to reach as anything other than dupes.

Dworkin’s deep pessimism, and the parts of the feminist movement that were drawn to it, went in directions we are still grappling with today. While it may not be fair to read her work as uniquely “anti-sex,” her antipathy toward sex work and sex workers can’t be brushed aside, nor can the fuel her work gave to punitive and carceral solutions to sexual violence — or her alliances, however tentative, with the religious right.

The renewal of interest in Dworkin’s work several years into the #metoo movement reminds us how central the threat and experience of sexual violence remains for many and how inevitably this fear will shape political consciousness. For leftist and socialist feminists, finding alternative solutions to sexual violence and the power structures that enable it remains a central and daunting task. In order to do so, we need to understand the appeal and limitations of Dworkin’s vision — as well as the movement history that shaped her work and its influence.

Dworkin came to radicalism early. At Bennington College — which she described as “a very distressing kind of playpen where wealthy young women were educated to various accomplishments which would ensure good marriages for the respectable and good affairs for the bohemians” — she became an antiwar activist. After her arrest for protesting outside the United Nations, she was held at the infamous Women’s House of Detention for four days. Years before she would develop into the movement author famous for her relentless descriptions and analysis of male sexual violence, she was quoted in the New York Times detailing her assault and questioning at the hands of a prison doctor obsessed with the sex lives of young college students. Following her graduation, Dworkin went to Amsterdam to write about the city’s anarchist movement and soon married the militant of whom she would write, “Some people need to fight all the time. If they can’t fight in the streets, they have to fight in the home.”

People are radicalized and join social movements for countless reasons, but pain is often one of them. Radical movements promise to transform individual pain, with its stigmas, shame, and isolation, into collective anger and action. Young feminist radicals like Dworkin brought many varieties of their own pain. Many had broken from traditional male-dominated families and communities only to be shaken by currents of the male New Left and revolutionary movements around the world that romanticized political violence. Many were also haunted by visions of what societies do with rebellious women (a vision sadly borne out in a Guardian essay which notes that despite her lifelong struggles, Dworkin may have suffered from extreme depression but didn’t “actually” go crazy like her fellow radical visionary Shulamith Firestone, who suffered from mental illness and isolation and died under horrific circumstances in 2012).

In the years Dworkin was publishing her early work, feminism was visible to an extent unimaginable a decade before. President Jimmy Carter declared 1977 “the year of the woman” and appointed Congresswoman Bella Abzug to head the influential National Woman’s Conference in Houston that year. Women of color and queer women organized groups that had a lasting effect on the movement: the National Black Feminist Organization was founded in 1973, and the Combahee River Collective, a group of black lesbian feminists, formed in 1974. In 1972, Johnnie Tillmon became the head of the National Welfare Rights Organization and wrote a seminal manifesto that claimed welfare as a core women’s issue.

At the same time, much of the radical feminist movement had splintered, and while early radicals had brought with them their experiences organizing in the Civil Rights, New Left, and antiwar movements, more and more of the women who entered the movement hailed from apolitical backgrounds. Unfortunately, these new activists were often disconnected both from the dynamic organizing of women of color that decade and the wider left. Alice Echols has called the movement that emerged at that moment “cultural feminism,” and it found expression in the founding of women-only spaces, alternative communities, and cultural practices. At their best, these were utopian projects that aimed to prefigure a more just future. But they often did not lend themselves to the kind of activism and organizing that marked the whirlwind period.

Next to these New Age goddess seekers, Dworkin’s work leaped off the page with the fury of an Old Testament prophet. Like many second-wave feminists, Dworkin was Jewish and born to a generation haunted by the Holocaust. She used the language of fascism to describe male violence, giving her pieces titles like “Letters from a War Zone.” In “A Battered Wife Survives,” she compared the psychological aftermath of her own experience of abuse to that of a concentration camp survivor. In a 1975 essay on rape based on a talk delivered at multiple universities, she wrote: “We must destroy the very structure of culture as we know it, its art, its churches, its laws, we must eradicate from consciousness and memory of all the images, institutions, and structural mental sets that turn men into rapists.”

It is a strange experience to read Dworkin’s work on rape today. In some ways, it lays out what are now familiar feminist insights about sexual violence: that rape has been defined as a property crime against men whose severity depends on the identity, race, and social status of the victim and her “ownership” by a husband, father, or master, rather than as a crime against the victim’s freedom. That far from an aberration, rape is embedded in systems of power and the violence used to uphold them: “Rape is committed by exemplars of our social norms; rape is a logical consequence of a system of definitions of what is normative,” she wrote in a sentence that could have easily appeared after the Kavanaugh hearings. Familiar as these insights have become, Dworkin was one of the few public voices that grappled with the implications; notably, she was one of the few feminists of any stripe willing to take seriously charges of sexual assault by Bill Clinton.

And yet, reading Dworkin now, the delight in transgression gives way at a certain point to a numbing sameness. The relentless naming of power and violence as male begins to grate, and not only because it feels like an impoverished understanding of gender. While Dworkin did not ignore divisions of class and race, there is little sense in her work that male violence might stem in part from men’s own traumas or powerlessness over their lives. In the 1975 rape essay, Dworkin calls for now-common solutions: rape crises centers, self-defense classes, and legal reforms, along with “squads of women police formed to handle all rape cases” and “women prosecutors on rape cases.”

But as feminism became institutionalized and professionalized, the upshot of those divisions became clear: the cultural transformation Dworkin saw as necessary for real change wasn’t coming, but we would get the female police and the soaring prison rates. And while Dworkin acknowledged that racism played a role in how rape was treated by authorities, she ultimately thought that men would “choose” loyalty to their sex above all else. Nor did she engage deeply with black feminists, who wrote extensively of the limitations of viewing “men” and “women” as defined social classes and expressed reluctance at invoking state-based solutions to violence.

From sexual violence, Dworkin turned to withering treatments of pornography and, finally, to intercourse itself. The progression implied a certain causality — that pornography and a “regular” heterosexual intercourse as defined in a male-dominated culture were part of the ideological apparatus that upheld male violence. It’s hard to remember how new and vital this analysis once felt, even to feminists who would go on to disagree profoundly. As Bright would note: “Along with Kate Millet in Sexual Politics, Andrea Dworkin used her considerable intellectual powers to analyze pornography, which was something that no one had done before. No one. The men who made porn didn’t. Porn was like a low culture joke before the feminist revolution kicked its ass. It was beneath discussion. Not so anymore!” In her struggle to get at the roots of power and violence, Dworkin took on everything from fairy tales to the Bible to countercultural male icons like Henry Miller. Like many radicals of the period, Dworkin saw culture as a terrain of struggle and rejected the division between politics and art.

Many of the recent reconsiderations of Dworkin, including the editors of this volume, speak of her vision as having “fallen out of fashion” and lament what was lost during the so-called sex wars of the 1980s, when feminist divisions over pornography fractured a movement already under strain from reactionary attacks. But these laments ignore what was at stake for those who came to oppose Dworkin’s vision.

They also ignore how influential her ideas were. In retrospect, it may appear that Dworkin “sealed her fate” by working with groups such as Women Against Pornography. But at its height, WAP was one of the most visible and influential feminist organizations, drawing support from well-known radical veterans like Susan Brownmiller and Robin Morgan, along with media icon Gloria Steinem and feminist writers such as Adrienne Rich and Grace Paley. The staged tours and pickets of Times Square eventually even received support from business interests looking to upgrade the area’s image and rental prices. And though Dworkin’s famous legal efforts to have pornography redefined as a civil rights violation largely failed in the courts, many anti-pornography activists and organizers went on to fight against (already illegal) sex work and “trafficking,” an effort that, as journalist Melissa Gira Grant documents, has become a crusade for numerous questionable NGOs and so-called rescue organizers, not to mention countless celebrities and rich women in search of a cause.

The feminists who challenged this trajectory included many queer women who saw the limitations of Dworkin’s Manichean sense of sex roles and gender identity. They were also radicals hoping to keep alive the possibility of transformation during dark political times. As Ellen Willis wrote in her review of Dworkin’s book on pornography:

Without contradiction there can be no change, only impotent moralizing. And in the end moralizing always works against women: the Andrea Dworkins rail against male vice; the George Gilders come forward to offer God and Family as the remedy. Which is why I find Pornography’s relentless outrage less inspiring than numbing, less a call to arms than a counsel of despair.

It was a prophetic statement about the ways in which morality, absent analysis and a vibrant movement, stands in for politics. And it’s an ironic one given that, a few years into the Reagan era, Dworkin would write Right Wing Women, her most sophisticated, provocative, and relevant book.

Dworkin is rightly chastised for her alliances to anti-pornography forces on the Right — yet it is possible that this pact allowed her to see what many others could not about the Right’s appeal. Offering close readings of now-forgotten but influential memoirs by right-wing women with titles like The Gift of Inner Healing and The Total Woman, Dworkin demonstrated how the religious right provided women what seemed like a workable set of rules through which to navigate male power and the threat of male violence: “For women, the world is a very dangerous place . . . The Right acknowledges the reality of danger, the validity of fear. The promise is that if a woman is obedient, harm will not befall her.”

It’s bracing reading for those still puzzling over how so many white women continue to support Trump. It seems clear that many are not unaware or “in denial” about his abuse of women; most charitably, it can be said they regard such abuse as an eternal and apolitical fact about the world; less charitably, that they view it as a foreseeable outcome for women who strayed into the celebrity den.

Right Wing Women contained still more insights: unlike liberals who were baffled by some women’s opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment or chalked it up to misunderstanding, Dworkin saw the centrality of the abortion issue and took seriously the appeal of anti-abortion politics: if motherhood were no longer coerced, what would that mean for their long struggles to accommodate themselves to it, and the status, however circumscribed, they gained from it?

Dworkin recognized the woeful inadequacies of employment as an alternative source of protection and freedom, given the low wages most women earn, the ubiquity of harassment on the job, the profoundly unfree nature of almost all workplaces, and the sense, not entirely unfounded, that the feminist movement coincided with the loss of the family wage that offered some security if not autonomy.

The focus of much of the #metoo movement on sexual violence and harassment, particularly in the workplace, offers an important challenge to socialists and feminists to envision and struggle to undermine the hierarchies that enable abuse in the workplace — and fight for the social benefits that allow women to walk away from abusive jobs and marriages.

I was talking to a friend recently about Dworkin and the limits of the dystopian.“You have to offer visions of transformation,” I said.“But do you?” she asked. “Maybe sometimes you just have to say that something is shit.”

Saying things are shit is in the air, and not just in the proliferation of dystopian novels and binge-worthy dramas. While many have attributed the renewed interest in Dworkin’s writings to the rise of the #metoo movement, rereading her work brought to mind the tone of much of today’s political writing, animated by despair at the global resurgence of ethnonationalism and the climate catastrophe. Going through Dworkin’s catalog of horrors sometimes feels like looking at one more picture of a polar bear on a tiny patch of ice.

In the face of such despair, the symbolic violence of writing takes on a new weight, as do models of violence turned inward. Dworkin was fascinated with Huey Newton’s notion of “revolutionary suicide” and Norman Morrison’s self-immolation in solidarity with the antiwar monks of Vietnam, which she used as a model for the end of Mercy. When presented with injustices without the possibility of redress, all we can do is gape, and perhaps, take some pleasure in the shape of the wreckage or our own willingness to confront it. This is what we mean when we talk about “disaster porn,” and probably a big part of what people mean when they say Dworkin’s own work was pornographic: spectacles that leave us enraged but helpless. If Dworkin seems newly relevant, this feeling of despair is probably a big reason why.

In a world that denies cruelty and violence, to speak of them unflinchingly and unapologetically can feel like liberation. And yet, we do not lack for eloquent statements of pain. Such testimonies are not unimportant, but they are deeply insufficient, especially when confronted with antagonists like Trump for whom, as is often observed, the cruelty is the point.

At the same time I was rereading Dworkin, I read the recent New York Times profile of scholar and prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Beyond marveling at finding such a thoughtful portrait of such a genuinely radical thinker in the Times, I was struck by the way it upended the way I’d been thinking about despair and hope. In the work of Gilmore and other prison abolitionists, it is precisely the horrors of the current system that demand an alternative: not hope or optimism or policy proscriptions, but a vision. Precisely because they understand the brutality of the current system of mass punishment, prison abolitionists, led by African-American women, insist on moving beyond this catalog of horrors.

There are no easy abolitionist solutions to sexual violence, and we can’t dismiss as purely reactionary the desire among many, perhaps rekindled by Dworkin’s vision, for some small measures of accountability. But in the face of our despair, however oddly comforting it might be, the search for an alternative vision is all we have.