The Green New Deal Needs WWII-Scale Ambition

We can end global warming pollution and build a just, green economy in ten years with a budget of $50 trillion a year.

The view from aerial tour of Hurricane Sandy damage of New Jersey's barrier beaches, November 18, 2012. Sonya N. Hebert / White House

It’s time for America to be ambitious again.

Congressional advocates of a Green New Deal are calling for a “national, social, industrial and economic mobilization at a scale not seen since World War II and the New Deal era” in order to decarbonize the US economy by 2030.

Taking the climate crisis seriously means getting the United States to net-zero or negative carbon pollution within ten years while working to undo the damage already done. Doing so involves reconstituting not only our electrical grid, but also our transportation system, agricultural system, financial system, built infrastructure, medical system, trade and manufacturing, land use, political system, gender relations, military — our entire economy, our entire relation to each other and to the rest of the world.

While all that may seem impossible to those on the fossil fuel industry payroll, it can be done if the United States mobilizes at a scale achieved in our nation’s history during World War II.

The Green New Deal resolution calls for the United States to reach “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions” “through a ten-year national mobilization.”

This target of rapid, total decarbonization is at odds with the goals of Trump’s administration and the projections of carbon polluter giants such as ExxonMobil; and is considerably more ambitious than recent Democratic Party leadership plans, which have been fixed on an 80 percent reduction from 2005 levels by 2050 benchmark since the Step It Up campaign of 2007.

Rapid, total decarbonization is also what is needed in this time of climate emergency.

The consequences of extracting and combusting hundreds of billions of tons of fossilized carbon in recent decades are with us now. Nation-states are crumbling from a degraded climate, with catastrophic droughts, floods, fires, storms, ocean rise, glacial retreat, and biodiversity collapse putting people in all corners of the globe in biblical peril.

If humanity does not end the burning of fossil fuels and reverse deforestation, the possibility that it will share the fate of the vast majority of all species to have existed on this planet — extinction — is unreasonably high. The price tag of insufficient action, as Harvard economist Martin Weitzman’s “dismal theorem” finds, is potentially infinite, “since catastrophes that would cause human extinction remain too plausible to ignore.”

The United States, the oldest continuous government on the planet and the greatest producer and beneficiary of carbon pollution, faces this peril as much as any other nation. Millions of Americans have become climate migrants within our borders as their homes and livelihoods have been destroyed. Our political and social institutions are falling apart as disaster capitalists rush to strip-mine what profit they can from our increasingly depleted natural and societal resources.

The consequences of the 1°C warming the planet has experienced so far are considerably more dire than scientific projections, leading the nations of the world to (non-bindingly) commit to trying to keep global warming below 1.5°C if possible, at most 2°C.

The commitments made by the Obama administration (and reneged by Trump) to bring climate pollution down by 80 percent by 2050 are insufficient to keep global warming below 2°C, let alone 1.5°C.

The Trump plan of inaction (at best) would lock in greater than 2°C warming within ten years, and likely lead to unimaginably catastrophic 4°C or greater. At some point, the global economy would see rapid decarbonization — through global catastrophe that would dwarf the scale of the Great Depression and World Wars.

We need to be in the green zone. Taking the climate crisis seriously means getting the United States to net-zero or negative carbon pollution within ten years. To get there, a mobilization like that achieved during World War II is needed.

To match a WWII-level mobilization today, US federal spending would reach somewhere between $30 trillion to $80 trillion a year.

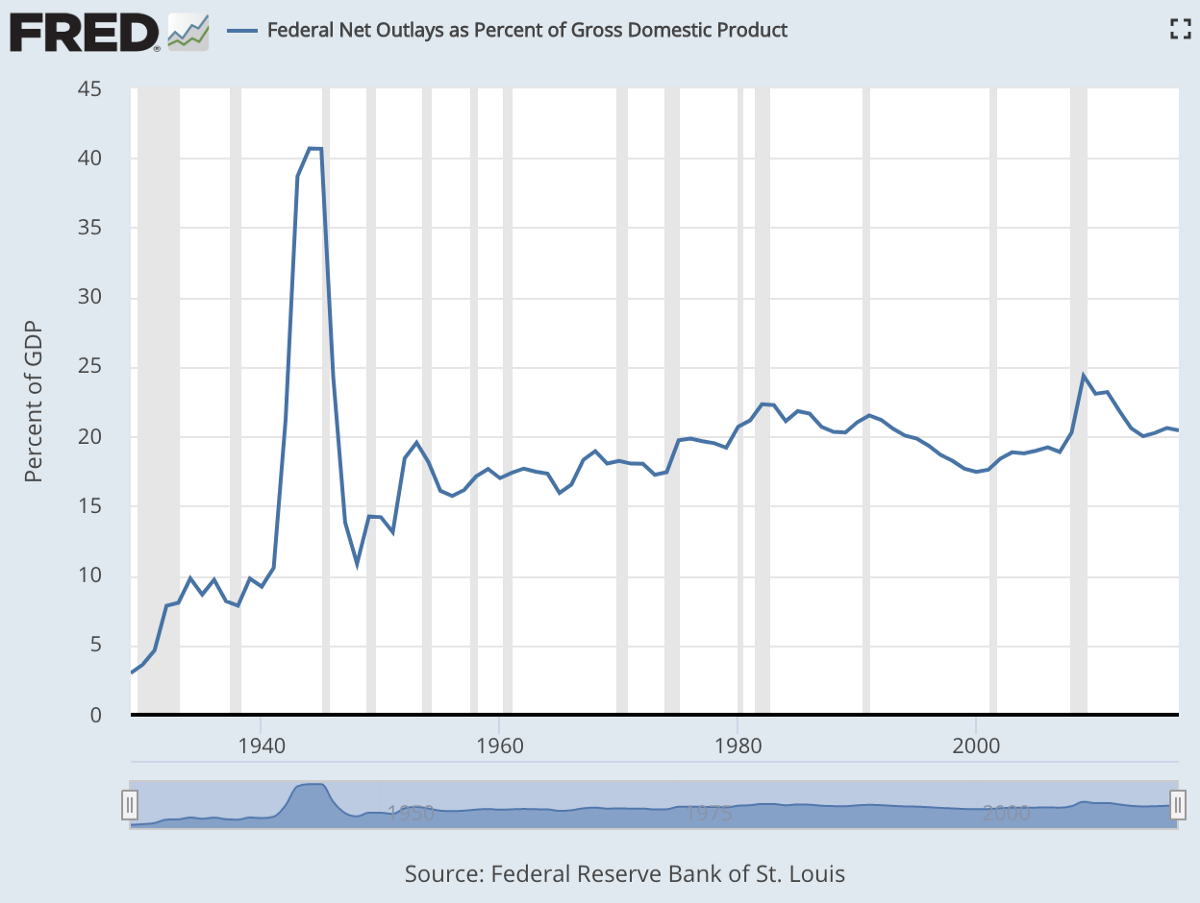

The nation’s mobilization for World War II saw federal spending grow from 10 percent of GDP (which represented a doubling from pre-Great Depression spending) to over 40 percent by 1945, vastly higher than federal outlays since.

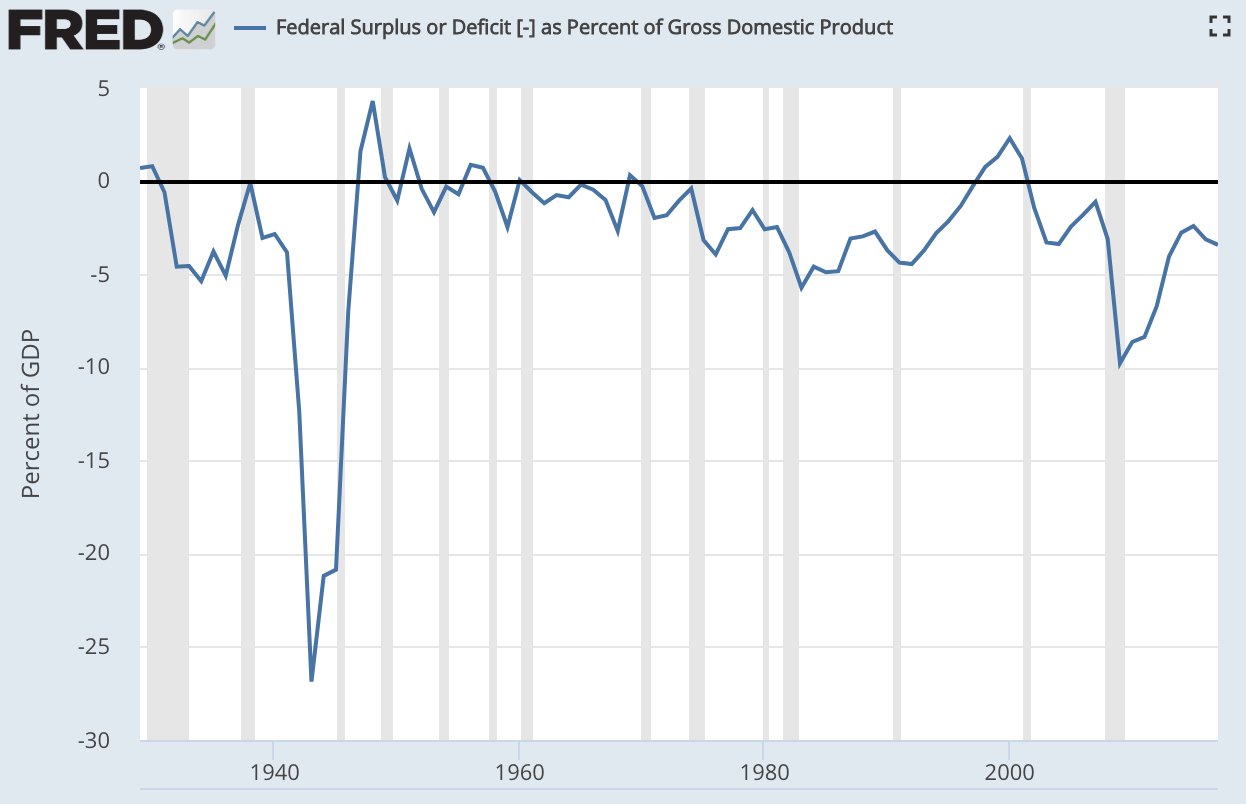

One of the most common attacks against any kind of federal investment in the health of its citizenry is the specter of “soaring deficits.” Again, if we look to the highly successful example of the New Deal and World War II, we can see that we have little to worry about. (There’s also the point that budgetary deficits are meaningless when the alternative to spending is extinction.) The federal deficit reached 25 percent of GDP at the peak of the WWII-spending boom, vastly higher than today’s deficits.

Note: As total US GDP grew dramatically thanks to the war mobilization, US federal spending increased not four-fold from 1940 to 1945 but seven-fold. The spending ramp-up from the start of the Great Depression to the peak of WWII mobilization is much more dramatic — a twenty-fold increase.

That previously unprecedented spending is better understood as investment — the US economy tripled in size from 1929 to 1959. As economic analyst Kimberly Amadeo summarizes, “the New Deal worked.”

Remarkably, the US’ historically high percentage of federal spending during World War II would put it at the low end of present-day spending in Europe:

Following World War II, federal government spending has remained stable at about 20 percent of GDP. (The 2009 stimulus very briefly increased spending to 25 percent of GDP.)

The US federal budget is currently about $4 trillion a year. If the federal government increased investment by seven to twenty times — paralleling the ramp-up that got the world out of the Great Depression, beat the Nazis, and made the United States the undisputed superpower of the free world — we would see an annual federal budget of about $30 trillion to $80 trillion a year.

We can end global warming pollution and build a just, green economy in ten years with a budget of $50 trillion a year.

But as the progenitors of the Green New Deal recognize, a technocratic focus on greenhouse pollution numbers misses the true peril and promise of this civilizational moment. “Because reshaping our environmental impact means reworking our economy,” Jedediah Britton-Purdy writes, “there will inevitably be competing visions about who deserves to benefit and what kind of economy we should build.”

The inconvenient truth of climate change is that neoliberal extractive capitalism is failing to provide the people of the world with basic stability, security, and dignity. The promise of democracy, justice, and equal rights that has served as America’s lodestar remains in default. The status quo is literally unsustainable. As Naomi Klein writes, the “triple crises of our time: imminent ecological unraveling, gaping economic inequality (including the racial and gender wealth divide), and surging white supremacy” are “inextricably linked — and can only be overcome with a holistic vision for social and economic transformation.”

We cannot undo much of the damage already done by the global fossil-fueled system of exploitation and oppression; but we can replace that system in short order with a Green New Deal, if only our ambition is high enough. As our own nation’s history attests, the potential budgetary price tag of investing in our future survival is not a limiting factor.