Why Non-Citizens Should Be Allowed to Vote

Undocumented immigrants are part of the political community just like any other resident. They should have full voting rights.

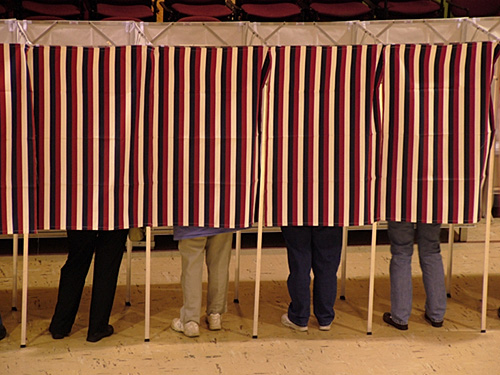

Voting booths are set up at a 2018 Minnesota primary election polling place inside the Westminster Presbyterian Church on August 14, 2018 in Minneapolis. Stephen Maturen / Getty

Imagine: what if today, instead of being consigned to the shadows, the more than 22 million noncitizen immigrants in the US were heading to the polls? Sound preposterous?

Voting by non-citizens is actually as old America itself. From the founding of the American Republic, voting rights were determined not by citizenship but by other criteria, such as race, gender, and property holdings. When women, post-emancipation African Americans, and poor white men were denied voting rights, it was due to elite antipathy — not because they lacked citizenship. Non-citizens in those years picked electoral winners and losers, and even held political office. What brought this period of “alien suffrage” to a close was simple nativism.

The case for noncitizen voting remains compelling: all residents are part of the political community in which they live and should therefore have a say in the local, state, and federal laws to which they’re subject. Without the means of choosing representation, non-citizen immigrants are a non-voting caste — disenfranchised pariahs in their adopted country. Noncitizen voting is a logical step to correct this injustice, and to make the ideals of American democracy more of a reality.

The Case for Noncitizen Voting

Today, about one in fourteen people in the US are noncitizen immigrants (lawful permanent residents, unauthorized immigrants, or legal residents on temporary visas). They live in virtually every state, city, suburb, and town. They’re teachers and students, physicians and nurses, musicians and construction workers. They pay taxes, raise their families, send their kids to schools, and make countless social and cultural contributions every day.

But while they’re denizens of the same communities and neighborhoods as voters, non-citizens are barred from entering the polling booth. While they live under the same policies set by legislative bodies, they have little ability to influence and select the representatives making those laws.

This exclusion is a fundamental violation of their self-determination — an affront to one of their most basic, inviolable rights. It turns millions of people into political subordinates, undermining the vitality of democratic life and making a mockery of American democracy. All US residents should be able to vote — whether they come from Delaware or the Dominican Republic.

The exclusion of non-citizens from the voting rolls has real consequences. Although hardly homogeneous, immigrants as a group tend to score low on many social indicators of wellbeing, including income, poverty, hunger, and education. Such outcomes are the result, at least in part, of political disenfranchisement. Politicians can enact discriminatory public policy and private practices — in employment, housing, education, health care, welfare, and criminal justice — and run xenophobic campaigns, secure in the knowledge that non-citizens won’t be able to punish them at the polls.

Historically, the acquisition of political rights, including voting rights, has been a vital tool for disempowered groups to achieve economic, social, and civil rights. Noncitizen voting would enhance the visibility and voices of immigrants, making government more representative, responsive, and accountable.

Extending suffrage would also benefit the larger society. We all share the same interest in having good schools, affordable housing, effective transportation, environmental justice, and so on. Allowing a permanent class of non-voters to persist on the margins benefits elites that wish to profit from undocumented people’s labor and divide workers between those with papers and those without them. Far from diluting the concept of citizenship, noncitizen voting would enrich it by fully incorporating immigrants. Rather than undermining democracy, it would counteract elite-driven policy and promote more robust democratic practices.

Finally, there’s a practical reason progressives should push noncitizen voting: just as restoring voting rights to felons and fighting voter suppression shore up democratic values while undercutting conservative foes, conferring the franchise on non-citizens is a boon for democracy that also boosts the prospects of progressive legislation.

Opponents of noncitizen voting might argue that if immigrants want to cast a ballot, they should just become citizens. But the naturalization process is no longer so simple. While most immigrants want to become citizens, they quickly run up against bureaucratic roadblocks and other daunting obstacles: steep application fees, interminable wait times, application backlogs, lack of access to the English and civics classes needed to prepare for the naturalization exam. It can take years to become a US citizen. In the meantime, undocumented immigrants are unable to vote on the issues crucial to their daily lives.

Another objection might be that a national community should have the power to determine who is and isn’t allowed in its borders, and that granting non-citizens voting right might alter its capacity to do so. But such a notion of self-determination forgets that US economic policies and military interventions abroad have destabilized countless countries and eviscerated many migrants’ own capacity for self-determination. From Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine to NAFTA and the war on drugs, US policy has triggered immigration from Latin America and undermined migrants’ “right to stay home.”

The caravan currently making its way from Honduras is only the latest example of the “Harvest of Empire.” The US has a clear obligation to accommodate the millions of economic and political refugees it has directly or indirectly set into motion by making life in their homeland untenable.

Noncitizen Voting Rights — A History

The history of noncitizen voting rights in the US is a long one.

During colonial times noncitizen voting was common and not particularly controversial, and the practice continued when the new states formed their constitutions. A logical extension of the revolutionary cry “No taxation without representation!”, “alien suffrage” also received rhetorical force from the democratic notion that governments derive their “just powers from the consent of the governed.” From 1776 to 1926, non-citizens in as many as forty states exercised their right to vote in local, state, and even federal elections, and in some cases held office.

For most of this period, noncitizen voting was seen as a means to train newcomer white Christian men to be good neighbors and promote active participation in the life of their new homes before their eventual naturalization. In frontier states, it was also a way to lure new white male immigrants to permanently occupy Native lands, diffusing pressure from women, Native Americans, and African Americans who demanded political and property rights.

With the influx of different kinds of immigrants, however, noncitizen voting rights became contentious, particularly when the newcomers challenged dominant groups. The War of 1812 slowed and even reversed the spread of alien suffrage in the North, in part by raising the specter of foreign “enemies.” In the lead-up to the Civil War, the South opposed immigrant voting because many of the new immigrants – particularly the Irish — opposed slavery.

After the Civil War, noncitizen voting rights were introduced throughout the South and into the West, spurred on by the need for new labor. The expansive voting rights provided an incentive for newcomers to settle in the new territories and states, helping fuel settler colonialism. More positively, noncitizen voting also fueled immigrant political engagement and incorporation — which is why it became the object of derision and target for obliteration.

Generally, states would require residency of six months to a year or more before granting voting rights. Wisconsin, which gained statehood in 1848, extended full voting rights in local, state, and national elections to “declarent aliens” (i.e. foreign born white persons who declared their intention to become citizens). Wisconsin’s model for enfranchising “aliens” proved popular; Congress passed a law with similar provisions for new territories (Oregon, Minnesota, Washington, Kansas, Nebraska, Nevada, Dakota, Wyoming and Oklahoma). After achieving statehood most states continued permitting “declarent aliens” to vote.

Noncitizen voting reached its peak during the 1870s and 1880s, when twenty states allowed it. By the close of the nineteenth century, most states had some experience with the practice.

But as the twentieth century approached, large numbers of Southern and Eastern European immigrants — who weren’t seen as “white” and who often held politically “suspect” views (think Italian anarchists and Jewish socialists) — began to settle in the US. These newcomers — along with burgeoning mass movements and third parties — posed a threat to the prevailing political and social order, and immigrant voting rights increasingly came under attack.

The nativism of the period was strikingly similar to rhetoric today: immigrants were characterized as “uneducated,” accused of stealing jobs from “real” Americans, scapegoated as paupers who would live off of taxpayers’ money, and denounced as immoral criminals. Population projects fretted that the US would soon become a non-white majority.

Gradually, state by state, lawmakers struck noncitizen voting from the statute-book. “Alien suffrage” came to an end — the victim of anti-immigrant backlash and World War I hysteria.

The abolition of noncitizen voting coincided with the enactment of other draconian measures, including literacy tests, poll taxes, felony disenfranchisement laws, and restrictive residency and voter registration requirements — all of which combined to disenfranchise millions of voters. Voter participation dropped precipitously, from highs of nearly 80 percent of the voting-age population in the mid- to late nineteenth century to 49 percent in 1924. Additional legislation drastically shrank the flow of immigrants into the US and limited the proportion of non–Western European immigrants.

For many decades, this history of noncitizen voting has been buried in the annals of American scholarship. But the US’s extensive experience with the practice could help spark its resurgence — in fact, there’s some evidence it already has.

Noncitizen Voting Rights Today

The US Constitution does not prohibit voting by noncitizens, and both state and federal courts have upheld noncitizen voting. The Supreme Court, for example, affirmed in the 1874 case Minor v. Happersett that “citizenship has not in all cases been made a condition precedent to the enjoyment of the right of suffrage.” In law and practice, the decision about who holds the franchise rests with states and localities. Taking advantage of that opening, a dozen cities in the US have extended voting rights to noncitizen immigrant residents over the past few decades, and still others have considered restoring noncitizen voting.

The contemporary revival of noncitizen voting initially emerged during civil rights mobilizations. The movement for greater community control in New York City led to the creation of local Community School Board Elections, which granted voting rights to any parent of a public school student (the elections were eliminated in 2002 for unrelated reasons). In 1983, the “rainbow coalition” that helped elect Chicago’s first African-American mayor, Harold Washington, successfully pushed for immigrant voting rights in local school councils.

Today, noncitizen voting is most common in Maryland: ten municipalities allow it in all local elections (partly because the state’s constitution gives localities the power to expand their franchise without state approval). In 2016, the same day Trump was elected, San Franciscans passed a ballot measure opening the franchise to noncitizen parents.

Another dozen jurisdictions have debated enfranchising non-citizens in local elections, including four towns in Massachusetts (Cambridge, Amherst, Newton, and Brookline). Legislators in Boston recently considered doing the same, as did those in Portland, Maine; and Burlington, Montpelier, and Winooski, Vermont. Large cities, such as Washington DC and New York City, have also weighed giving non-citizens voting rights in local elections.

The particulars of these cases vary: while some have only covered documented immigrants (i.e. those that hold green cards but are not yet citizens), other campaigns have pressed for voting rights for all non-citizens, regardless of their status. Some efforts have been led by immigrant rights organizations, while other campaigns arose at the initiative of elected officials. Some measures have been passed — or were defeated — by a majority of voters in a jurisdiction (through a ballot proposal), while other measures have been passed — or were defeated — by elected representatives (as local statutes).

Globally, more than forty-five countries on nearly every continent permit voting by resident immigrants. The European Maastricht Treaty in 1993 granted the right to vote to all Europeans in European Union countries other than their own, expanding what has been practiced for years in Sweden (1975), Ireland (1975), the Netherlands (1975), Denmark (1977), and Norway (1978). Non-citizens vote in countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, North America, and New Zealand.

The US would be wise to join the rest of the world.

Expand the Vote

The level of political exclusion of noncitizen immigrants approximates the level of disenfranchisement of women and African Americans in the past. In New York City, 22 percent of the population are non-citizens; in Los Angeles, that number is 33 percent. In many districts, a quarter to a half of the population is prevented from selecting the political representatives that govern their lives.

What do these conditions mean for such basic democratic principles as “one person, one vote,” “government rests on the consent of the governed,” and “no taxation without representation”? Can politicians claim to support democratic rule if they disenfranchise millions of residents?

Critics of noncitizen voting often have an easy answer: get in line and wait to receive citizenship if you want to vote. But they overlook both the difficulty of attaining citizenship (there is no “line” to hop in) and the role that the US government plays in pushing people from their home countries.

As the scholar Lisa Garcia Bedolla has argued, those who focus “solely on the actions and responsibilities of individual immigrants . . . ignore the role of the state, and state-sanctioned economic actors, in facilitating, subsidizing and making possible, migration.” Elites are happy to let businesses cross borders — but when immigrant workers try to do so, they’re stripped of their rights on the job and in the political sphere. Granting non-citizens voting rights — an idea with deep roots in American history — would provide them with an important means to defend their interests.

Just as the Civil Rights Movement fought to extend the franchise to African Americans, expanding the franchise to new Americans would empower the excluded and help forge winning voting blocs. It would make American democracy more inclusive and vibrant. And it would tilt political power away from elites.

So ignore the nativists. Let noncitizen residents vote.