Seattle, “the Soviet of Washington”

Decades before Amazon dominated the city, Seattle was the fiery site of labor unrest, radical action — and the US's only true general strike.

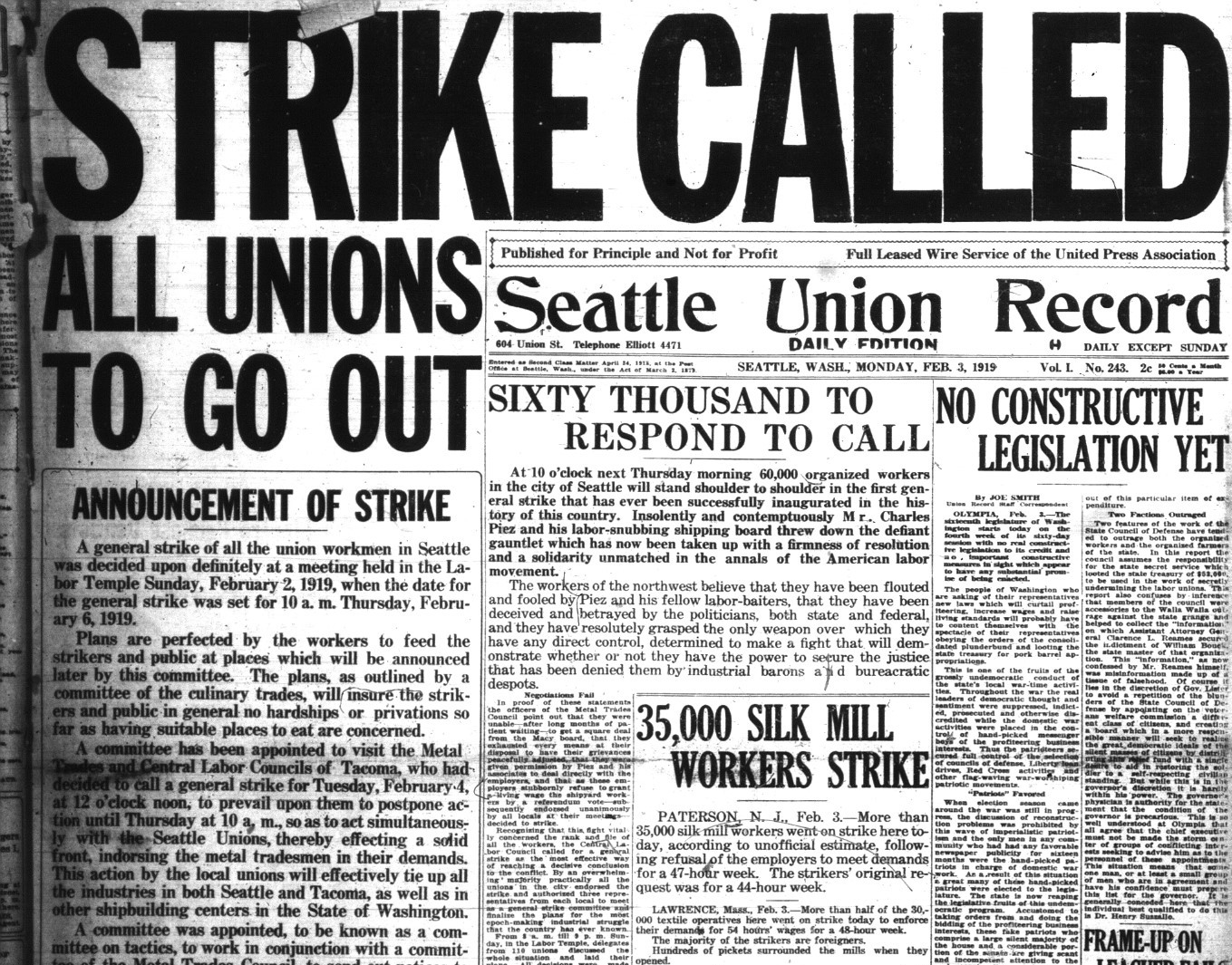

The front page of the Seattle Union Record at the beginning of the Seattle General Strike, February 3, 1919. University of Washington

Seattle gleams under the grey skies that characterize its climate. Container ships from China wait in Elliott Bay to unload, while tour boats head out to Alaska’s shrinking glaciers. The Great Wheel towers over Pier 57, and there are tourists everywhere. Two gigantic sports arenas dominate the southern end of the waterfront, where in times past seamen brawled and the longshoremen struck the great ships — losing in 1916, winning at last in 1934. The football stadium is the prize of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who obtained the public funding for its construction. The best seats in the house sell for more than $1,000 and the approaches are lined with upscale bistros and bars. Just south of Lake Union, Allen’s Vulcan real estate company is building a head-office complex for another tech firm, Amazon, complete with interlinked spherical glasshouses enclosing a miniature rainforest. Facebook and Google are also moving in. Powered by these new developments, the Emerald City has the fastest growing population of any major urban area in the US. The world’s two richest men, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, both reside here.

Seattle flourishes, then — it is an important place. But can we ask: what sort of place? A stage set, perhaps, for the new Gilded Age, in which corporate wealth and “vibrant” street life can distract the eye from all manner of social contradictions. Seattleites don’t mind the rain; in fact, they love the outdoors. However, public space is at a premium and access to its beaches severely restricted. Tech workers take great pride in Seattle’s high rating for “livability,” yet the cost of housing is rising even quicker than in the Bay Area and the traffic is often unbearable. Hundreds sleep on the street each night. Tent cities appear, reminiscent of the 1930s “Hooverville” shanty town erected in the mud flats south of the business district, and just as unwelcome to the authorities. Meanwhile elsewhere in the city, second homes abound.

Still, there are ghosts dwelling here: old memories — dimly held, to be sure. Here is Yesler Way, once better known as Skid Road because of the logs rolled downhill along its course to Henry Yesler’s sawmill on the shore. Nowadays a nondescript thoroughfare dotted with cafes frequented by tourists, including a branch of the city’s ubiquitous Starbucks chain, it used to heave with disreputable saloons, brothels, and flophouses, making Skid Road synonymous with any district where the down-and-out may gather: places that are rough, sometimes radical. The Industrial Workers of the World put down roots in this quarter among loggers, itinerant farm workers, and miners bound for the Yukon, as well as the shipyard workers who led the Seattle General Strike of February 6–10, 1919, the only true general strike in US history and the one occasion when American workers have actually taken over the running of a city — the sort of endeavor which earned this state, now given over to the billionaires of the new economy, the appellation “the Soviet of Washington.”

Pacific Hub

Seattle is situated on a vertical strip of land between Puget Sound — an “inland sea” off the northern Pacific — and the freshwater Lake Washington. Nonindigenous settlement began with the arrival of a couple of dozen migrants from Illinois in 1851, a few years after the Oregon Treaty fixed the border between the United States and British America at the 49th parallel. The incomers named the township after Chief Sealth of the area’s Duwamish and Suquamish tribes. Upon incorporation by the Washington Territorial legislature in 1869, the city had just two thousand inhabitants. This figure would swell to eighty thousand by the turn of the century. As places of note, Seattle and Tacoma, thirty miles to the south, were the warring creations of competing northern railroads. Two days closer than California to Vladivostok and Asian markets, Seattle became the main distribution hub for the northern Pacific Rim, usurping San Francisco’s former hegemony over the entire Pacific Slope. In addition to its command of Washington State’s forests and the great wheat belt of the Palouse steppe, Seattle also dominated the trade and fisheries of Alaska, whose economy was boosted by an influx of prospectors during the Klondike gold rush. Jobs in distributive and wholesale trades, as well as shipbuilding, attracted migrants fleeing slums, unemployment, and poverty in the East — blacklisted railroad workers, redundant miners, famished wheat farmers. When the mayor of Butte, the class battleground in Montana, visited Seattle in 1919 he recognized large numbers of ex-copper miners working in its shipyards. If Minnesota and neighbouring farm states appealed to the more prosperous Scandinavian immigrants, Swedes above all, western Washington with its extractive industries drew in the much poorer Norwegians and Finns, though core activists in the General Strike came from the British Isles.

The timber economy of Western Washington was dominated by the Weyerhaeuser Lumber Trust, which mounted a full-scale assault on the vast stands of ancient cedar, western hemlock, and Douglas fir forest. Timber from Washington State would buttress the copper mines of the West, underpin its railroad lines, and build its rapidly expanding cities, above all in California. The loggers toiled for twelve hours a day, seven days a week, and slept in company shacks. Conditions in the mills were neither easier nor safer: giant saws, deadly belts, horrific noise, dust, smoke and fire. When the heavy winter rains came, the lumberjacks wrapped up their bindlestiffs and fled to Skid Road. There they would remain, sinking into debt, until job sharks and lumbermen herded them back to the woods. They were despised by Seattle’s bourgeoisie as “timber beasts.”

The well-to-do lived away from Skid Road on the leafy boulevards of First and Capitol hills, along Magnolia Bluff and overlooking the lake in Madrona and Washington Park. They boasted a flourishing cultural life, including a fine university built in the French Renaissance style in Union Bay. The politicians and their newspapers might feud — what to do with the infamous Skid Road? — but Seattle was staunchly progressive: women’s suffrage, co-operatives, municipal ownership, growth. As it expanded from a low-lying base around Pioneer Square, the tops of surrounding hills were lopped off — “regraded” — for the benefit of developers. The neighboring town of Ballard was annexed in 1907 and the harbor municipalized four years later, a blow for the big railway and shipping interests struck on behalf of small manufacturers, minor shipping lines, and farmers anxious to force down rates. The new Port of Seattle developed some of the best waterfront facilities in the country, including the sort of moving gantry crane still used in container terminals today. The construction of a ship canal connecting Puget Sound with Lake Washington also commenced in these years.

In the 1890s, utopian land-settlement schemes in Seattle’s vicinity drew in idealists and free-thinkers. Harry Ault, Union Record editor, spent his teenage years in Equality Colony, Skagit County, in a family of disenchanted Populists. He recalled his mother feeding workers in Coxey’s Army of the unemployed as it passed through Cincinnati in 1894. In the 1910s, Seattle’s established working-class communities — Ballard, “South of Yesler,” and into Rainier Valley — were blighted by poor housing, threadbare amenities, and lack of access to the Sound, the green forests, or the great mountain ranges beyond — all that the city cherished, and still does. This rarely registered as a problem, however, among municipal reformers.

Manual labor was dangerous as well as poorly rewarded: wrote one labor activist at the time, “Every day or so some unlucky shipyard workers would be carried out in the dead wagon.” When the US Commission on Industrial Relations held hearings in the city in 1914, Wisconsin’s great labor specialist, John Commons, noted a “more bitter feeling between employers and employees than in any other city in the United States.” Seattle’s workers fought back against their oppressors as a class — and as a class, created a culture of their own: unions that were “clean,” not run by gangsters; a mass-circulation labor-owned newspaper, the Union Record — it became a daily in 1918, the only one of its kind; its circulation topped one hundred thousand in the aftermath of the strike. Socialist schools ran lectures indoors and out; IWW singing groups; community dances, and picnics. Milwaukee may have had its socialist congressman, Victor Berger; Los Angeles almost had a socialist mayor, Job Harriman; but Seattle’s socialists were working class and “Red.” Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs judged Washington State the “most advanced” and long suspected that it might be the first to achieve socialism. Electoral success proved elusive, but Washington claimed several thousand paid-up adherents, ranking second only to Oklahoma in the proportion of party members per head of population. The Left took control of the party in Seattle in 1912 after a protracted factional struggle. Proponents of industrial unionism, they were thorns in the side of national party officials who supported Samuel Gompers, conservative president of the craft-based American Federation of Labor. Seattle workers overwhelmingly supported the principle of industrial unions — and by implication, workers’ control. “I believe that 95 per cent of us agree that the workers should control industry,” wrote Ault. Still, most unions retained their affiliation to the AFL. Progressives were critical of craft divisions but thought the IWW impractical and wanted to remain in the “mainstream.” They looked to James Duncan, chair of the Seattle Central Labor Council, for leadership. A metal worker born in Fife, Scotland, clearly influenced by syndicalism, his compromise formula came to be known as “Duncanism.” The city’s labor movement was centralized around the SCLC, which coordinated rather than supplanted the craft unions to ensure that all contracts for crafts within a particular industry ran concurrently, allowing for bargaining as a unit. Though a consistent critic of the IWW which challenged the AFL from the left, Duncan nevertheless acknowledged it as “a pacesetter.” In this environment, social democracy and revolutionary unionism could intermingle. Seattle was an IWW no less than a Socialist Party stronghold, home to its western newspaper, the Industrial Worker, and scene of free-speech fights ending in mass arrests, beatings, and victories. “Two card” workers were commonplace: an AFL card for the job, an IWW card for the principle.

Class solidarity wasn’t all-embracing, however. As late as September 1917, the Daily Call reported that one of the issues in a meatpackers’ strike was the workers’ demand for a white cook. Alice Lord, talented organizer of the city’s women workers, above all its waitresses, was a committed exclusionist. The relatively few black workers in Seattle at this point, just 1 percent of the population, took what work they could, including as strikebreakers in the longshoremen’s strike of 1916. There were, however, signs of a shift in attitudes among the white majority. Seattle’s most popular street speaker, the socialist’s firebrand Kate Sadler, talked at black churches and was a scathing critic of exclusion and shop-floor segregation. The Union Record likewise insisted on the need “to break down racial barriers in the West.” Ault told a congressional hearing on Japanese immigration that he had “little patience with racial prejudice,” recalling his early childhood in segregated Kentucky.

Voyage of the Verona

The opening of the Panama Canal in August 1914 lifted West Coast trade, offsetting the recession which had hung over the States since the previous year. Seeking a share of the shipping companies’ profits, longshoremen struck on June 1, 1916 for a closed shop, higher wages, and a nine-hour day. Workers in San Francisco quickly settled, but Seattle and Tacoma stayed out. When Andrew Furuseth, head of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, defended the San Francisco leadership at an SCLC meeting in September, he was chased from the hall with shouts of “coward” and “quitter.” The strike shook Seattle. The Washington National Guard deployed along its harbor, which “resembled a battleground. Non-union men went uptown looking for fights. Union longshoremen beat up scabs on docks and ship. There were fist fights, knife fights, docks bombed, pier fires, shots fired and murders.” By the strike’s end on October 4 — Tacoma and a number of smaller locals held out longer — there were 850 scabs working the docks and the longshoremen had lost control of the waterfront. They returned to work under the open shop plus the “fink hall” which screened out the International Longshoremen’s Association and IWW.

The shingle weavers of Everett, the “City of Smokestacks” thirty miles to Seattle’s north, were engaged in their own desperate strike — victims of nothing short of a reign of terror. “At every stage the Everett police and the private lumber guards took the initiative in beating and shooting workers for speaking on their streets,” recalled Anna Louise Strong, who reported on the unrest for the New York Evening Post. On November 5, 1916, three hundred Wobblies embarked on the steamships Verona and Calista bound for the mill town. No one aboard expected a warm welcome from the authorities, but murder was not foreseen. On its arrival, the Verona was met with gunfire from lawmen and vigilantes. At least five workers were killed, all of them unarmed, and dozens injured. Two “citizen deputies” were also slain, although the fatal shots were fired from the shore, seventy-four people aboard the Verona were charged with murder. The Everett massacre was in some ways a Pacific Northwest Peterloo: an assault on free speech, fair play, and the very notion of “rights.” Disbelief, then anger, coursed through Seattle’s working-class districts. The IWW turned Everett into a cause célèbre, stumping the West on behalf of the accused. “These seventy-four men represent the migratory worker, the element that while necessary is ferociously exploited in this Western country,” declared IWW organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn at a dozen rallies. “They want the good things in life as much as any other member of the human race and they are organizing in the IWW to get them.” There was a sea change in popular opinion, a massive swing to the left. The SCLC persuaded Seattle lawyer George Vanderveer, “Attorney for the Damned,” to assist the Verona defendants. He secured their acquittal the following spring. The Daily Call reported that IWW membership had risen to twenty thousand and that the Wobblies now employed a dozen paid organizers — exaggerated figures, perhaps, but after the serious setback on the docks the IWW had undeniably gained fresh impetus.

The Wobblies took this forward momentum into the woods: a general strike involving some fifty thousand loggers and mill workers. “They breathe bad air in the camps. That ruins their lungs. They eat bad food. That ruins their stomachs. The foul conditions shorten their lives and make their short lives miserable,” lumber organizer James Thompson told the Industrial Commission during hearings in Seattle. The IWW had always idolized the itinerant workers of the West. They set out from Seattle to organize them and succeeded. Their demands were typically straightforward: an eight-hour day, no work on Sundays or public holidays, sanitary kitchens and satisfactory food, single spring beds with clean bedding, no workers under sixteen in the mills, no discrimination against IWW members. In July 2017, the IWW held a mass rally of 3,500 workers at Seattle’s Dreamland Rink. The meeting began with the singing of “Solidarity Forever.” Kate Sadler and IWW organizer J. T. “Red” Doran were the featured speakers.

The police, sheriffs, National Guard, and US Army responded to the strike with savage repression. The jails filled up; prisoners were beaten. Strike leader James Rowan and twenty IWW members were arrested in a single swoop in the city of Spokane. The federal government organized a rival organization, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen. As the strike spluttered, the Wobblies adjusted their tactics: a “strike on the job,” the loggers working their desired eight-hour shifts. The conclusion, in March 1918, was a sensation: the eight-hour day won and a long list of improvements in the camps. It was one of the IWW’s greatest accomplishments and a source of class pride well beyond the ranks of the IWW. Duncan drew the obvious moral: “the terribly effective force which takes the name of IWW … is largely made up of men who consider regular trade unionism ‘too slow.’” It was, he acknowledged, a “threat to the prestige of trade unionism on the Coast.”

Nevertheless, traditional unionism also thrived amid the industrial boom stoked by federal military procurement as Woodrow Wilson took the US into the First World War. “A red-letter year in the history of organized labour,” Duncan celebrated in July 1917. “A dozen new unions have been organized and all of the Seattle unions are flourishing.” He singled out the streetcar men whose membership had risen to 1,600; the telephone operators with nearly 1,100. Industrial action by the laundresses in particular had struck fear into Seattle’s respectable classes. Within a week, all the city’s major laundries had more or less closed down. Hotels and clubs began to run short of clean linen. The bourgeois Seattle Times fretted that the “family washtub would emerge from oblivion in thousands of Seattle homes.” The laundry workers took their case into the neighborhoods: a fair in Fremont, a parade in Rainier Valley. Stung by hostile public opinion, the employers rapidly capitulated. But if such triumphs deepened working-class consciousness, they brought down fierce repression, foretelling worse to come. William Preston, Jr, has revealed that “the lumber operators of the Northwest provided the initial impetus in the evolution of federal policy” — that is, the “Red Scare” and the Palmer raids. The workers’ movement in Seattle was strong, certainly, but not in Gramsci’s sense hegemonic. US entry into the European bloodbath in April 1917 turned dissent into treason. Gloves off, the federal government moved decisively against the IWW, indicting its top leadership. In Chicago, 101 members were tried and convicted of a range of alleged conspiracies. State vigilantism was visited upon Seattle, regarded as a center of both pro-German and pro-Bolshevik sentiment. The Bureau of Investigation in Washington, D.C. despised the city’s workers as “the scum of the earth” who recognized “no law and no authority save the policeman’s night stick or physical violence.” There were police raids, ransacked offices, mass arrests. Emil Herman, state secretary of the Socialist Party was charged with violations of the Espionage Act and imprisoned in the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. Hulet Wells, a former president of the SCLC, was sentenced to two years in federal prisons for passing out “No Conscription” handbills, along with Sam Sadler, one-time president of the longshoremen.

Feting the Shilka

In this extraordinarily tense atmosphere, the revolution came to Seattle on the Friday before Christmas, 1917. The Russian cargo vessel Shilka, red flags flying, steamed into Elliott Bay. Seattle’s socialists, its Wobblies, its dockers, metal workers, waitresses and shingle weavers, scrambled to the docks to greet the newcomers, as did naval officers and city police wary that the ship might contain Bolshevik gold, even perhaps munitions. In fact, the Shilka carried only beans and peas in its hold, and simply needed to refuel. But the arrival of a soviet of Russian sailors was momentous in itself. For the workers, its arrival greatly added to the festive mood. The sailors were fêted. There were testimonials, speeches and spontaneous singing — the “Marseillaise,” also the “Red Flag.” Hundreds of Seattleites jammed into the IWW Hall on Second Avenue where they greeted a young sailor, Danil Teraninoff, on stage with rapturous applause. “Never in Seattle has there been such a demonstration of revolutionary sentiment as at the moment the Russian fellow worker ascended the platform,” reported the socialist Daily Call. The visit of the Shilka sealed the extraordinary romance of Seattle’s working people with the October days, their passionate sympathy and solidarity with the revolution unparalleled in an American context. According to the late Philip Foner, “no labour body was a more consistent defender of the Russian revolution than the Seattle Central Labor Council.” Seattle delegates to AFL national conventions pressed for official recognition of the fledgling workers’ state, to no avail. The longshoremen intercepted railroad cars with loads labeled “sewing machines,” unearthing rifles and ammunition bound for Admiral Kolchak’s White armies on the Siberian front. The IWW resolved that they would “rather starve than receive wages for loading ships on a mission of murder.” The authorities, alarmed when not hysterical, “discovered,” among other things, Bolshevik conspiracies which trade unionists had every practical reason to deny. Until recently historians tended to accept these denials at face value, in so doing diminishing these remarkable events. On the contrary, the Russian Revolution was indeed a factor — a contradictory one, yes: inspiring the Left while terrifying the upper classes — in Seattle’s General Strike.

The political culture of Seattle in these years was shaped not only by its own tumultuous industrial-relations history but also by currents sweeping through working-class movements internationally. The Union Record published letters from Lenin including his “Letter to American Workers”; the Industrial Worker reported on a Labour socialist conference in Leeds where Ramsey MacDonald, flanked by Tom Mann, Sylvia Pankhurst, and Bertrand Russell, “hailed” the Russian Revolution. The new spirit of industrial radicalism spread far beyond its natural home in the IWW. Even where issues with management were “pure and simple,” bitter conflicts ensued. The AFL also felt the heat, its collaboration with employers and strict insistence on the sanctity of contracts, jurisdictional division by craft, and the authority of national officials rejected by growing numbers of workers.

The celebrations of 1917 were the prelude, then, to the great strikes of 1919. Seattle workers saw in the October Revolution their own image, the embodiment of what they were fighting for at home. “No single event,” wrote Duncan, “throughout the whole world today can, from the standpoint of workers everywhere, compare in importance with the successful piloting of the Russian Soviet Republic past the treacherous rocks of international capitalist greed and the determination of these plunderers to ruin what they cannot rule.” When two thousand longshoremen, overflowing their hall, celebrated the second anniversary of the Revolution on November 7, 1919, they rose in “tremendous cheering,” as the IWW’s J. T. Doran walked from the vestibule to the rostrum and began to speak. Doran, free on bail from the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, delivered, according to Magden, a rousing speech in which he described the workers’ revolution in Russia as “the most stupendous event since the fall of feudalism.”

Union City

By the end of the First World War, trade union membership in Seattle had quadrupled since 1915 to create, in effect, a closed-shop city. The General Strike would require no pickets, since there were no strikebreakers. Prejudice toward minorities eased, challenging management’s ever-ready divide-and-rule tactic. On the eve of the strike, Japanese unions appealed to the SCLC to join the strike committee and were accepted. “Even in the midst of strike excitement, let us stop for a moment to recognize the action of the Japanese barbers and restaurant workers who, through their own unions, voted to take part in the General Strike,” commented the Union Record. “The Japanese deserve the greater credit because they have been denied admission and affiliation with the rest of the labor movement and have joined the strike of their own initiative. We hope that this evidence of labor’s solidarity will have an influence on the relations between the two races in the future.” Black workers were accepted as full members of Seattle’s unions later the same year. The General Strike began with an appeal from the shipyard workers to the SCLC for support in a pay dispute following a period of wartime wage repression. There were thirty-five thousand shipyard workers in Seattle out of a total population of around three hundred thousand — fifteen thousand more in Tacoma. The industry fused together the two sectors of the local working class, the seasonal lumber and harvest workers and the city’s skilled trades, in a potent combination. Seattle had delivered more vessels to the Navy than any other port, even though its labor movement was strongly anti-war. Perhaps as many as one hundred thousand workers, including many unemployed, answered the General Strike Committee’s call. For the best part of a week, they fed the people, patrolled the streets, and celebrated workers’ power as a lived reality, until the combined weight of the forces ranged against them — the police and the special constables drafted in by Seattle’s belligerent mayor, Ole Hanson; the federal troops deployed by Secretary of War Newton Baker; the big newspapers; and the national leaders of the AFL and its affiliates — broke the striking unions’ resolve.

At the outset of the hostilities, Anna Louise Strong wrote that a Seattle walkout wouldn’t in itself greatly trouble the big commercial combines in the East. “But, the closing down of the capitalistically controlled industries of Seattle, while the workers organize to feed the people, to care for the babies and the sick, to preserve order — this will move them, for this looks too much like the taking over of power by the workers.” Stirred by the Everett case, Strong had taken a job as second-in-command at the Union Record. Probably an IWW member, she lived and worked in Socialist circles, also retaining acquaintances from her earlier life — including Russian émigrés, one a friend of Lenin’s. She organized much of the paper’s international coverage, notably a Russia department, and also wrote its editorials; as often as not she was the voice of the General Strike.

Against a remarkable backdrop of communist uprisings in Berlin, Vienna, and Budapest, red flags on the Clyde, and the hot summer in Turin, the Seattle strike fired the starting pistol for an extraordinary year of working-class rebellion in the States, the like of which has not been seen since: the Boston police strike; industry-wide action in steel, coal mining, and textiles. The subsequent era of working-class retreat began with the shattering of the IWW, the splintering and demise of the Socialist Party, and the employers’ counterrevolution — the American Plan. In Seattle itself, the Emergency Fleet Corporation cancelled orders for new vessels, forcing thousands of shipyard workers into redundancy, while the Waterfront Employers’ Association reintroduced the open shop. But labor radicalism didn’t die after 1919. The General Strike and IWW militancy lived on, if underground; also in the vivid recollections of old Wobblies and in the battles of young socialists in the 1930s. Along with an underlay of Scandinavian progressivism, this legacy laid the foundation for Washington’s Cooperative Commonwealth movement, which brought an alliance of CIO unions and progressive farmers to power in Olympia and elected the communist Hugh DeLacy to Congress. In governing circles, the strike wasn’t forgotten. It was in 1936 that FDR’s postmaster general, David Farley, would ironically raise a glass to “the forty-seven states and the Soviet of Washington,” a phrase later popularized in the writings of Mary McCarthy.

Boeing to Amazon

During the Second World War, Seattle was transformed into “Jet City.” The Boeing bombers — the B-17s, B-29s, and B-47s, as well as the B-52s of Dr Strangelove fame — which rained destruction from the skies on occupied Europe and then on Korea, were constructed in a sprawling plant backing on to the Duwamish river and another in Renton, together employing as many as forty-five thousand people. When government orders began to dry up in the mid-1950s, the company invested heavily in passenger jet airliners to escape what executives nervously referred to as “the peace problem.” The success of the 707 and 737 made Seattle all but a company town. The sudden termination of the postwar boom in 1971 therefore came as a shock. Boeing slashed its production workforce from eighty-five thousand to twenty thousand and unemployment climbed to 14 percent, the highest rate in the country. A three-decade tech boom, however, beginning with Microsoft’s expansion in the suburb of Redmond, fifteen miles to the northeast, in the mid-1980s, has erased memories of this downturn for anyone who didn’t live through it. Amazon presently employs forty thousand in the city spread across three dozen sites and occupies more office space than the next forty largest companies combined. It has used this leverage to block a municipal employment tax intended to raise funds for affordable housing. The company congratulates itself for investing in its hometown, yet five-sixths of the $668 million poured into infrastructure improvements around its South Lake Union campus has come from the public purse — such is the fine print in the latter-day “gospel of wealth.” There are gated suburbs in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, once the habitat of the IWW loggers. The Port of Seattle still thrives, but the old labor gangs upon which the waterfront’s solidarity was constructed have been replaced by crane operators and truck drivers, far fewer in number, though still occupying strategic positions in global commodity chains.

Does anything of 1919 endure? Is there an inheritance? There have been other times, though few as yet, which contain glimpses of this older history, as well as potentially offering something new. Eight decades after the General Strike, a rare alliance of blue-collar workers, environmentalists, and other alter-globalization activists — the “Teamsters and Turtles” — disrupted the World Trade Organization conference in Seattle, temporarily overwhelming the police and cutting off the convention center from the rest of the city, while steelworkers marched the waterfront. Defying curfews, orders to evacuate, and the imposition of a fifty-block “no protest zone” in the downtown district — edicts reinforced by the Seattle and King County police, Washington National Guard, and US military with tear gas, rubber bullets, concussion grenades, and baton blows — the protestors forced the WTO to adjourn in confusion, cancelling Clinton’s gala address. The workers of 1919 who took control of their city were as brazen and courageous — and then some, defiant even in the face of the cruelest measures taken against them — mass incarceration, deportation, murder. If their rule over Seattle only lasted five days, they were five days that mattered.