George Orwell and the Proles

Though his pessimism about the working class ebbed and flowed throughout his life, George Orwell ultimately saw workers as the only force that could build an egalitarian, socialist society.

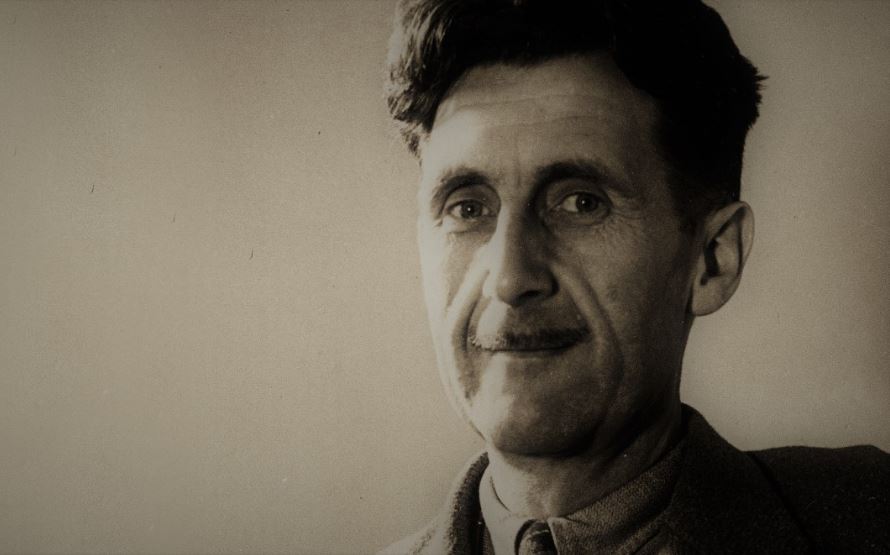

George Orwell. Wikimedia Commons

George Orwell was one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. He’s lionized by many on the Right and criticized by many on the left, yet relatively little is known about his socialist writings and politics.

In Hope Lies in the Proles: George Orwell and the Left, socialist scholar John Newsinger gives an overview of Orwell’s work and political trajectory. Aware of the political difficulties posed by Orwell with left-wing audiences — such as his support for the Cold War — Newsinger faces his task with political courage, presenting the English writer warts and all.

For Newsinger, Orwell was, until his death, a democratic socialist profoundly identified with the working class, which he saw as the agent of socialist transformation. Even in his most pessimistic moments, he saw in the working class the only potential for humanity, as the class that had the most to gain from a reconstruction of society. And it was the ups and downs of the working-class struggle of his times that, according to Newsinger, explain his work and his politics.

At Wigan Pier

This comes to light for the first time in Orwell’s 1937 book The Road to Wigan Pier, an account of life in a working-class community in northwest England. According to Newsinger, Orwell wrote it as a political act to show that notwithstanding the British economy’s recovery from the depths of the Depression, unemployment in the north of England, with all its attending misery, was still rife. He focused on the region’s miners, who were only beginning to recover from the failure of the general strike of 1926, denouncing their dangerous working conditions and the concomitant annual toll of accidents and deaths.

But Newsinger argues that Orwell’s clear sympathy and identification with the Wigan Pier miners was colored by skepticism of their political potential, underneath which lurked an element of disappointment at the absence of any indication of imminent revolt. This is, writes Newsinger, where Orwell posed for the first time the question that would motivate much of his future life as a political writer: why do the unemployed and the underpaid not rebel in circumstances such as those found among the miners in northwest England?

In the specific case of Wigan Pier, Orwell himself held that an insurrection there, as well as any insurrection in the Britain of that time, would have been suppressed with the resulting “futile massacres and a regime of savage repression.” But he attributes the absence of a rebellious spirit among the workers to their incorporation into the new forms of consumption that ensued after World War I, with the availability of “cheap luxuries” — fish and chips, art-silk stockings, tinned salmon, cheap chocolate, the movies, the radio, strong tea, and the football pools — as sources of immediate satisfaction.

Orwell might have had a point. Yet his analysis was limited by the lack of a broad historical perspective of the up and downs and complexities of working-class consciousness. He failed to see how it was affected in Britain and elsewhere by war, patriotism, economic depression, and the conservatism of trade union and socialist bureaucracies.

Orwell also blamed, in the second part of The Road to Wigan Pier, what he branded as the “middle class left,” the “left-wing secret teetotalers with vegetarian leanings” who, according to him, alienated the working class, attracting instead all sorts of cranks among whom, reflecting his own prejudices, he indiscriminately listed together quite different types of people such as ”the ‘fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist.”

Newsinger argues that Orwell should have focused instead on the demoralization of the working class caused by the massive betrayal of the Labour government of 1929-1931, when former Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald effectively defected to the Conservatives in order to lead a reactionary National Government, implementing massive cuts that inflicted great hardship on millions of working-class people.

I must admit that when I first read The Road to Wigan Pier as part of my early socialist education, I was very sympathetic to Orwell’s criticisms of the “middle class left.” Coming from a country — pre-revolutionary Cuba — where political differences were not channeled through cultural, lifestyle expressions, I could not understand why sections of the Left in the United States and England would want to exacerbate their isolation and marginality from the rest of society by adopting visibly different lifestyles.

Later on, I learned about cultural politics and the constructive role they sometimes played in left-wing movements and politics — for example, the alternative social worlds forged by many European social democratic and communist movements. Such social worlds can’t be entirely written off. But I remain wary of any attempt to identify the Left with a particular cultural lifestyle. The approach of currents of the post-sixties left, with their adherence to the “counterculture,” leads to cultural self-isolation at best, or sectarianism and elitism at worst.

A left program that aims at reaching power to bring about major change is about liberating classes, groups, and individuals from exploitation and oppression based on class, race, gender, or national origin, not about endorsing particular lifestyles.

Alternative lifestyles in and by themselves do not necessarily challenge the system. One example is the phenomenon of bohemia that developed in developed capitalist societies where relative abundance, at least in comparison with less developed countries, allows for the creation of spaces for alternative lifestyles.

As Jerrold Seigel points out in Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830-1930, Parisian bohemia developed out of a generalized need to release the repressed feelings and emotions of everyday bourgeois existence. Bohemia took up residence in the margins of society, often in conditions of poverty falling just short of threatening physical survival.

But, as Siegel shows, it never posed a threat to the bourgeoisie and to capitalism. It developed in the interstices of that system. It is interesting that in much of economically less developed Latin America, the “bohemian life” refers to people who, due to unusual work and leisure schedules, enjoy a late night social life at bars, cafés and night clubs. It does not imply any critique of bourgeois social norms as such.

The Spanish Working Class in Arms

Whereas in his Road to Wigan Pier Orwell saw a defeated English working class still on the defensive, on his arrival in Barcelona shortly afterwards during the Spanish Civil War, he found “a town,” as he described in his Homage To Catalonia, “where the working class was in the saddle.” It was a revolutionary situation where “practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists . . . . every shop and café had an inscription that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black . . . it was a town in which the wealthy classes had practically ceased to exist . . .”

In Barcelona, Orwell joined the United Marxist Workers Party (POUM), which along with the anarchists, was the Republican camp’s leftmost force. They were fighting against the 1936 Francoist military insurrection, which had brought the Spanish fascist Falange and the traditional clerical and monarchist right wing together to stage a military coup against the elected Republican government.

The Republican camp was deeply split. On one side were supporters, such as the anarchists and the semi-Trotskyist POUM, of the social revolution staged by urban workers, artisans, and farm laborers shortly after the Republic was declared in 1931. On the other side were liberals, social democrats, and especially the Spanish Communists, who following Stalin’s Popular Front policies — and aided by substantial material support from the Soviet Union — maintained that the Republic should foreswear social revolution. They believed it should limit itself to the defense of political democracy against Fascism, to avoid alienating the Spanish middle classes and potential international allies like France and the United Kingdom.

Siding with the POUM and the anarchists, Newsinger argues that the Popular Front policy actually failed because neither Britain nor France with its Popular Front government did anything to aid the Spanish Republic, thereby enabling its defeat. In addition he points out that the social revolution that the Popular Front opposed was an actually existing struggle, which the anarchists and the POUM wanted to support and lead, and not an invention of their propaganda.

Similarly, he argues that the POUM strategy of completing the revolution and encouraging revolt in the military-controlled Spanish colonies, which had served as the base from which Franco’s forces invaded Spain in 1936, was a viable political option that cannot be dismissed out of hand.

The Spanish Civil War experience left an indelible mark on Orwell’s politics and moved him sharply to the left. His participation in the workers and popular revolt in Barcelona as a member of a POUM militia devoid of class divisions in its ranks gave him, as Newsinger put it, “a foretaste” of the socialist egalitarian society he believed in. This experience reaffirmed Orwell’s orientation to the working class and identification with the poor.

Orwell also had his anti-Stalinism reaffirmed after the Soviet leader intervened in favor of the Republicans, putting his political commissars and secret services to work building prisons and assassinating left-wing opponents like POUM leader Andreu Nin. He had originally developed his anti-Stalinist impulses during his association with the British Independent Labour Party (ILP), a small but significant party to the left of the Labour Party. The Spanish Civil War also reaffirmed the anti-imperialist politics and feeling of solidarity with the “colored working class” that he had developed based on his experience as an imperial policeman in British-ruled Burma.

As Orwell put it after his return from Spain, it was important to keep in mind that “the overwhelming bulk of the British proletariat does not live in Britain, but in Asia and Africa,” pointing to the British super-exploitation of India, which was “the system which we all live on.”

Newsinger notes, however, that Orwell never adopted revolutionary Marxism, even though in many occasions, as in the case of Spain, he reached similar practical conclusions like the need for revolution. According to Newsinger, Orwell’s political formation had been influenced by the ILP, which he had joined in the 1930s along with many other leftists rejecting the Labour Party’s betrayals of the working class.

Under the ILP’s guidance he joined the POUM militia when he went to Spain to fight against Franco. The ILP, which achieved a certain influence and parliamentary representation in the 1930s and 1940s, proposed a parliamentary road to socialism. Accordingly, Orwell subscribed to the notion that the road to socialism was through the election of a parliamentary majority, but that in light of the inevitable armed resistance of capitalism and its supporters, that majority would have to take the necessary forceful measures to overcome that resistance.

Orwell’s Disappointment

The defeat of the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War and the onset of Word War II marked the downturn of Orwell’s expectations for the working class’ revolutionary potential.

Newsinger quotes him still insisting, in 1942, in the “fundamental decency” of workers. Trying to hold fast to his faith in working class agency, during the early forties he argued that in the long run the workers would nevertheless end up taking up the struggle for a better world. “The struggle of the working class,” Orwell wrote “is like the growth of a plant. The plant is blind and stupid, but it knows enough to keep pushing forwards towards the light, and it will do this in the face of endless discouragement.”

Even years later in his dystopian 1984, talking through the Winston Smith character that echoed many of Orwell’s thoughts, he insisted that the “proles” (the workers in the book) were the ones with the potential to blow the totalitarian ruling party to pieces. The problem was, he wrote there, that they could only rebel if they became conscious of their own strength, and they could not become conscious of their strength until they rebelled.

Orwell’s persistent concern with class agency led him, at the beginning of the war, to look into the growth of the “middle class” in economically developed countries like Britain, and how it fit with the working-class struggle. He did this in his 1941 The Lion and the Unicorn where, given the inability of the ILP to become a major party, he called for the formation of a new socialist party.

This party was to have its mass following in the trade unions but would also draw into it what he labeled the growing middle class: skilled workers, technical experts, airmen, scientists, architects, and journalists who would become most of “its directing brains.” What Orwell also called the “new technical middle class” included what Marxists would consider major sectors of the working class such as skilled workers. He considered their support crucial to the socialist cause.

At the same time, however, the disappointed Orwell berated the workers themselves: the defeats that the workers’ movements had experienced throughout the world since the Russian revolution, he held, were their own fault. In country after country the organized working-class movements had been violently crushed and the workers abroad had looked on and done nothing. To the British working class, Orwell argued, the massacre of their comrades in Vienna, Berlin, or Madrid had seemed less worthy of their consideration than “yesterday’s football match.” Even more disappointing to him was the total lack of solidarity that the English working class had shown for “colored” workers in the colonies.

Moving away from the revolutionary perspective he had acquired based in Barcelona declaring it “exaggerated,” Orwell decided to support the war and to concentrate on fighting fascism. Recognizing the weakness of the British left within the antifascist camp, and that in fact the Soviet Union and the United States had saved Britain from defeat, led him to new conclusions. He decided to join forces with the left wing of the Labour Party, which he regarded as the best that could be expected within the existing relation of forces in Britain, and accepted the offer to become literary editor of the left-wing Labour Party newspaper Tribune at the end of November 1943.

Yet unwilling to give up on the working class, he continued to engage, as Newsinger writes, with more radical socialist ideas. For instance in the American journal Partisan Review, he criticized the Clement Attlee Labour government’s “failure of nerve” in confronting capitalism, and hoped wistfully that the Labour government might take on the capitalist class in the future.

Nevertheless, Newsinger laments, Orwell was not able to escape the defense-of-the-status-quo logic of the Labour left. At Tribune, he went along with Labour left leader Aneurin (Nye) Bevan, urging that troops be used to break a bus drivers’ strike so that miners could go to work. And during the economic crisis of the late forties, he completely toed the Labour government’s austerity line. As Newsinger tells it, once the Labour Party fully embraced the decision to “run capitalism rather than abolish it,” Orwell was unable to resist the pressure to go along with its policies.

It was only after the war that Orwell returned to socialism and his hopes for a classless society. He did so by advocating in Tribune the idea of a socialist federation in Europe. Orwell naively believed that the United States, which he saw as preferable to the Soviet Union because of its democratic political system, would support it.

Orwell contradicted his own optimism about the United States during the same period, writing in Partisan Review that the United States stood as an obstacle to socialism, and that the situation for socialists was hopeless. For Newsinger, it was this pessimist outlook that characterized a late Orwell irremediably disappointed in the working class.

The Later Years

As the Cold War between the Soviet bloc and the Western powers broke out in the late 1940s, Orwell — like the American leftist writer Dwight Macdonald, with whom he corresponded extensively — came out in support of the West as the lesser evil. As Newsinger explains it, in spite of the horrors of the capitalist system that he had so virulently attacked in his writings, he saw it as at least politically democratic in contrast to Stalinism.

But I also think that Orwell’s pragmatism and seeming allergy to a long-term political perspective would not allow him to consider a “third camp” stance of “neither Washington nor Moscow,” which already existed but was politically and organizationally weak.

The two main works of his last years — Animal Farm (1944) and 1984 (1949) — are to be understood in the context of his growing opposition to Stalinism, which grew into a general concern with totalitarianism. Orwell still holds on to a socialist perspective in Animal Farm. There he clearly postulated a left wing if not an outright revolutionary alternative to the capitalist status quo. His socialist perspective became much attenuated in 1984, where the working-class alternative is a distant hope.

These books were manipulated by the Western powers in their imperial struggle with the Soviet Union and international communism. Newsinger writes how the CIA demanded revisions of the British-made film Animal Farm, which the agency had financed, eliminating any semblance of radical collective protest from the book.

But this manipulation should not have come as a surprise to Orwell. He knowingly participated in Western Cold War propaganda efforts.

In 1948, Clement Attlee’s Labour government established the British Information Research Department (IRD) to counter Communist propaganda in the UK and the British empire. As Newsinger relates in his scrupulously detailed account of Orwell’s Cold War–era collaboration, Orwell agreed to have his writings used by the IRD for anticommunist propaganda. Orwell might have been induced to work with the IRD because the agency’s program put forward social democracy, as embodied in the Labour Party, as a positive alternative to Communism.

According to Newsinger, however, after the publication of 1984, by far the most influential of his works, Orwell became “very worried,” as he wrote to his publisher Frederick Warburg, about the political manipulation of that book.

Through his literary agent Leonard Moore, on July 22, 1949, Orwell wrote to the United Automobile Workers (UAW) and to the American Socialist party newspaper Socialist Call clearly stating that 1984 was “NOT INTENDED as an attack on Socialism.” The book, Orwell wrote, was instead directed to expose “the perversions to which a centralized economy is liable and which have already been partly realized in Communism and Fascism.” It opposed “totalitarian ideas” and was set in England to show that English-speaking countries were not exempt from this danger.

The most deplorable chapter of Orwell’s collaboration in the Cold War was his handing to the IRD of names of known and suspected Communist supporters and sympathizers. When Orwell began to work with the IRD, that agency was trying to recruit leftists opposed to Stalinism. Orwell referred people such as Franz Borkenau, a then well-known left-wing anti-Stalinist writer, for hiring. And he also provided the IRD, on May 2, 1949, with a list of people he regarded as too unreliable to be hired as they had, in his view, acted as apologists for the Soviet Union. He had extracted these names from a much larger list of “fellow-travelers” that he and an associate had compiled for their own information.

Newsinger clearly sees Orwell’s conduct as inexcusable. Nevertheless, he strives for a fuller understanding of the author’s actions. Newsinger points out that there is no credible evidence that the list ever damaged the job prospects of any particular individual outside the IRD (and, as far as their job prospects inside the IRD, it was highly unlikely that the agency would in any case, hire anyone who had expressed any sympathy for Communism). Most importantly, Newsinger adds, at the same time that Orwell was turning over his list to the IRD, he was actively involved in opposing any McCarthyite witch hunt of Communists, and the curtailment of their civil liberties.

Fully aware of many leftists’ ambiguous attitudes towards Communism, Newsinger also draws a line between his critique of Orwell and that of those left critics whose not-so-hidden-agenda is to undermine Orwell’s credibility as an opponent of Stalinism because they supported the Soviet bloc as “socialist” or at least progressive. These are the kind of people, Newsinger argues, unwilling to speak up on behalf of the victims of Stalinism, first for fear of alienating an ally against Nazism, and then to avoid being labeled by other leftists as having supported the West in the Cold War.

In attacking Orwell, Newsinger argues, they ignored that in opposing the persecution of Communists in Britain, Orwell was supporting the civil liberties of people “who would quite cheerfully have seen him arrested, forced to confess by whatever means necessary, put on trial and shot.”

It is also worth pondering the extent to which Orwell’s collaboration might be related to his political pessimism regarding the possibility of socialist or even progressive change. As it emerges from Newsinger’s account, Orwell’s support for the Labour Party, even for its Tribune left-wing, was never commensurate in quality and intensity with his previous support for the ILP and even less so for the Spanish working class of the thirties. His pessimism, combined with the bitterness provoked by organized Communism’s attacks against him, may have provoked in him a degree of Stalinophobia uncontrolled by an internal political discipline. Neither did he have a positive view of the future that could rescue him from this reaction.

Orwell’s late collaboration with the propaganda apparatus of Western imperialism is a sad, regrettable, and inexcusable fact. Yet there was something about him that made him different from the liberal Cold War ideologists like Sidney Hook, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and the intellectuals around the liberal organization Americans for Democratic Action. He may have given up on the possibility of a workers’ revolution, settling instead for the Tribune left in the Labour Party, but unlike the typical Cold Warriors, he never subscribed to the growing pro-capitalist consensus of the postwar years.

As Newsinger argues, he mistakenly believed that his support and participation in Cold War institutions like the IRD was to protect the possibility of democratic socialism, rather than capitalism, against the Soviet Union and its supporters. And notwithstanding his disillusion with the working class as an agent of change, he remained loyal to his truth, even in his dystopian 1984, that “hope lies in the Proles.”

Yes, Orwell supported the Cold War and the Labour Party’s disciplining of the working class for the sake of the economic stability of capitalism. But he inspired many, as Newsinger put it, “by his support for and involvement in workers’ revolution, by his taking up arms against Fascism and by his opposition to Stalinism . . . What mattered was the way that his writings from the 1930s and 1940s still spoke to me and others, were still relevant to our concerns in the modern world.”