A Radical Defense of the Right to Strike

Why do workers have a right to strike? Because it’s one of the best means they have to resist their oppression.

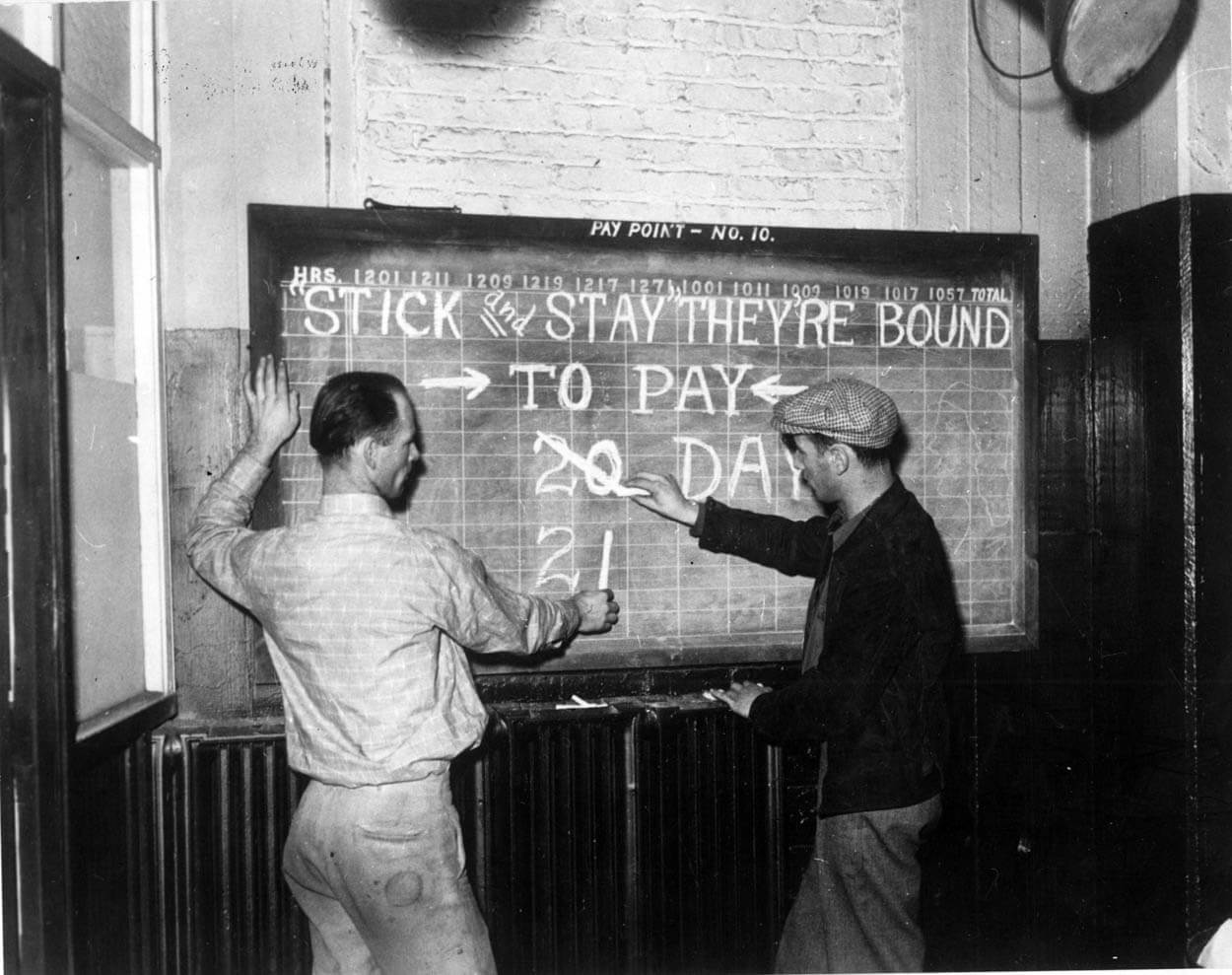

Striking workers update a strike calendar during the Flint sit-down strike, 1936. Walter P. Reuther Library / The Labor and Working-Class History Association

Every liberal democracy recognizes that workers have a right to strike. That right is protected in law, sometimes in the constitution itself. Strikes are also one of the most common forms of disruptive collective protest. Even with the dramatic decline in strike activity since its peak in the 1970s, work stoppages can still have a significant impact on our lives. Just over the past few years in the US, illegal strikes by teachers paralyzed major school districts in Chicago and Seattle, as well as statewide in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Colorado; a taxi driver strike influenced debates and court decisions regarding immigration; and demonstration strikes by retail and food-service workers were instrumental in getting new minimum wage and other legislation passed in states like California, New York, and North Carolina.

Yet strikes present a dilemma for liberal societies. For most workers to have a reasonable chance of success, they need to use some coercive strike tactics, like mass picketing.

But those tactics violate the law and infringe upon what are widely held to be basic liberal rights. On what basis, then, can the right to strike be justified?

The Dilemma

A strike is a work stoppage to achieve some end. But “work stoppage” means different things in different parts of the labor market. Higher skilled, low-supply workers — who are harder to replace and as a consequence typically enjoy better wages, hours, and conditions — can carry off a reasonably effective strike with little coercion and no significant law-breaking. So long as they exercise adequate discipline, they can slow or stop production altogether. Take the 2016 Verizon strike. While the telecom company tried to use replacement workers those replacements could not do the job effectively. After seven weeks, the company still was unable to service existing lines, let alone install new ones. It ended up conceding on important worker demands.

Lower skill, high-labor-supply workers in sectors like service, transportation, agriculture, and basic industry are in a different situation. These kinds of workers, in part because they are in such great supply, tend to have less bargaining power and therefore usually face lower wages, longer hours, and worse working conditions. They are also more vulnerable to forms of illegal pressure, wage theft, and other abuses. These are the workers we intuitively think should have the strongest case for a right to strike.

Yet even if all of those workers walk off and respect the picket, production will continue rolling because replacements are much easier to find, train, and put to work. The collective refusal to work doesn’t pack the same punch. This is one reason why McDonald’s and Walmart workers have stuck to single-day strikes — they’d be replaced otherwise.

To have a better shot of succeeding, the majority of easily replaced workers often have to use some type of coercive tactics. They must prevent managers from hiring replacements, prevent replacements from taking struck jobs, or prevent work from getting done in some other way. To be clear, by coercive, I don’t mean violent. Historically, it has not been workers but the state and employers’ private thugs who have committed most of the strike-related violence. Workers have suffered violence when exercising perfectly legitimate forms of coercion. The classic coercive tactics are sit-down strikes (occupying the workplace to prevent work from being done) and mass pickets (surrounding a workplace so no people or supplies can get in or out).

Both tactics fly in the face of liberal capitalism. A basic principle of political morality in any liberal capitalist society is that all persons enjoy basic liberties on the condition that they extend the same basic liberties to everyone else and that these liberties are enshrined in law. You are free to exercise your basic liberties so long as you do not coercively interfere with others in the enjoyment of their liberties.

Coercive strike tactics are inimical to a number of these basic liberties. They violate the property rights of owners and their managers, they abridge the freedom of contract and association of replacement workers, and they threaten the everyday, background sense of public order of a liberal capitalist society. It is no surprise then that these tactics are almost entirely illegal in the United States, as are many other solidaristic tactics that were once a standard feature of American labor activism. But again, in many cases, if workers can’t engage in mass pickets or sit-downs, then they have little hope of exercising a meaningful right to strike.

The only way to resolve this dilemma is to ask what, here and now, has priority: the basic liberties of liberal capitalism, as they are enforced in law, or the right to strike? And if it’s the right to strike, what kind of right is this and how can it be justified?

The Facts of Oppression

Class-based oppression is inextricable from liberal capitalism. While meaningful variation exists across capitalist societies, one of the fundamental unifying facts is this: the majority of able-bodied people are forced to work for members of a relatively small group, who dominate control over productive assets and who, thereby, enjoy control over the activities and products of those workers. There are workers, and then there are owners and their managers.

Workers are pushed into the labor market because they have no reasonable alternative to looking for a job. They cannot produce the goods they need for themselves, nor can they rely on the charity of others, nor can they count on adequate state benefits. Depending on how we measure income and wealth, about 60 to 80 percent of Americans fall into this category for most of their adult lives.

This structural compulsion is not symmetric. A significant minority of the population has enough wealth — whether inherited or accumulated or both — that they can avoid entering the labor market. They might happen to work, but they are not forced to do so.

The oppression, then, stems not from the fact that some are forced to work. After all, if socially necessary work were shared equally, then it might be fair to force each to do their share. The oppression stems from the fact that the forcing is unequal —that only some are made to work for others, producing whatever employers pay them to produce.

This structural inequality feeds into a second, interpersonal dimension of oppression. Workers are forced to join workplaces typically characterized by large swathes of uncontrolled managerial power and authority. This oppression is interpersonal because it is power that specific individuals (employers and their managers) have to get other specific individuals (employees) to do what they want. We can distinguish between three overlapping forms that this interpersonal, workplace oppression takes: subordination, delegation, and dependence.

Subordination: Employers have what are sometimes called “managerial prerogatives” — legislative and judicial grants of authority to owners and their managers to make decisions about investment, hiring and firing, plant location, work process, and the like. Managers may change working speeds and assigned tasks, the hours of work, or, as Amazon currently does, force employees to spend up to an hour going through security lines after work without paying them. They can fire workers for Facebook comments, their sexual orientation, for being too sexually appealing, or for not being appealing enough. They can give workers more tasks than can be performed in the allotted time, lock employees in the workplace overnight, require employees to labor in extreme heat and other physically hazardous conditions, or punitively isolate workers from other coworkers. They can pressure employees to take unwanted political action, or, in the case of nurses, force employees to work for twenty-two different doctors.

What unifies these seemingly disparate examples is that, in all cases, managers are exercising legally permitted prerogatives. The law does not require that workers have any formal say in how those powers are exercised. In fact, in nearly every liberal capitalist country (including social democracies like Sweden), employees are defined, in law, as “subordinates.” This is subordination in the strict sense: workers are subject to the will of the employer.

Delegation: There are additional discretionary legal powers that managers enjoy not by legal statute or precedent but because workers have delegated these powers in the contract. For instance, workers might sign a contract that allows managers to require employees to submit to random drug testing or unannounced searches. In the United States, 18 percent of current employees and 37 percent of workers in their lifetime work under noncompete agreements. These clauses give managers the legal power to forbid employees from working for competitors, in some cases reducing these workers to near indentured service. The contract that the Communications Workers of America had with Verizon until 2015 included a right for managers to force employers to perform from ten to fifteen hours of overtime per week and to take some other day instead of Saturday as an off-day.

While workers have granted these prerogatives to employers voluntarily, in many cases it’s only technically voluntary because of the compulsion to work. This is especially true if workers can only find jobs in sectors where these kinds of contracts proliferate.

Which leads to the third face of oppression: the distributive effects of class inequality. The normal workings of liberal capitalism elevate a relatively small group of owners and highly paid managers to the pinnacle of society, where they accumulate most of the wealth and income. Meanwhile, most workers do not earn enough to both meet their needs and to save such that they can employ themselves or start their own businesses. The few that do rise displace others or take the structurally limited number of opportunities available. The rest remain workers.

Dependence: Finally, managers might have the material power to force employees to submit to commands or even to accept violations of their rights because of the worker’s dependence on the employer. A headline example is wage theft, which affects American workers to the tune of $8 to $14 billion per year. Employers regularly break labor law, by disciplining, threatening, or firing workers who wish to organize, strike, or otherwise exercise supposedly protected labor rights. In other cases, workers have been refused bathroom breaks and resorted to wearing diapers, denied legally required lunch breaks or pressured to work through them, forced to keep working after their shift, or denied the right to read or turn on air conditioning during break. In particularly egregious examples, employers have forced their workers to stay home rather than go out on weekends or to switch churches and alter religious practices on pain of being fired and deported. There are also the many cases of systematic sexual harassment, in those wide regions of the economy where something more than a public shaming is needed to control bosses.

In all these instances, employers are not exercising legal powers to command. Instead they are taking advantage of the material power that comes with threatening to fire or otherwise discipline workers. This material power to get workers to do things that employers want is in part a function of the class structure of society, both in the broad sense of workers being unequally dependent on owners, and in the narrower sense of workers being legally subordinate to employers. The oppression lies not just in the existence of these powers, nor in some capitalist bad apples, but in how these powers are typically used. Managers tend to use these powers “rationally,” to exploit workers and extract profits.

Each of these different faces of oppression — structural, interpersonal, and distributive — is a distinct injustice. Together they form the interrelated and mutually reinforcing elements of class domination that are typical of capitalist societies.

Defenders of liberal capitalism insist that it provides the fairest way of distributing work and the rewards of social production. They often speak in the idiom of freedom. Yet liberal capitalism fundamentally constrains workers’ liberty, generating the exploitation of one class by another. It is this oppression that explains why workers have a right to strike and why that right is best understood as a right to resist oppression.

The Right to Resist

Workers have an interest in resisting the oppression of class society by using their collective power to reduce, or even overcome, that oppression. Their interest is a liberty interest in a double sense.

First, resistance to that class-based oppression carries with it, at least implicitly, a demand for freedoms not yet enjoyed. A higher wage expands workers’ freedom of choice. Expanded labor rights increase workers’ collective freedom to influence the terms of employment. Whatever the concrete set of issues, workers’ strike demands are always also a demand for control over portions of one’s life that they do not yet enjoy.

Second, strikes don’t just aim at winning more freedom — they are themselves expressions of freedom. When workers walk out, they’re using their own individual and collective agency to win the liberties they deserve. The same capacity for self-determination that workers invoke to demand more freedom is the capacity they exercise when winning their demands. Freedom, not industrial stability or simply higher living standards, is the name of their desire.

Put differently, the right to strike has both an intrinsic and instrumental relation to freedom. It has intrinsic value as an (at least implicit) demand for self-emancipation. And it has instrumental value insofar as the strike is an effective means for resisting the oppressiveness of a class society and achieving new freedoms.

But if all this is correct, and the right to strike is something that we should defend, then it also has to be meaningful. The right loses its connection to workers’ freedom if they have little chance of exercising it effectively. Otherwise they’re simply engaging in a symbolic act of defiance — laudable, perhaps, but not a tangible means of fighting oppression. The right to strike must therefore cover at least some of the coercive tactics that make strikes potent, like sit-downs and mass pickets. It is therefore often perfectly justified for strikers to exercise their right to strike by using these tactics, even when these tactics are illegal.

Still, the question remains: why should the right to strike be given moral priority over other basic liberties? The reason is not just that liberal capitalism produces economic oppression but that the economic oppression that workers face is in part created and sustained by the very economic and civil liberties that liberal capitalism cherishes. Workers find themselves oppressed because of the way property rights, freedom of contract, corporate authority, and tax and labor law operate. Deeming these liberties inviolable doesn’t foster less oppressive, exploitative outcomes, as its defenders insist — quite the opposite. The right to strike has a stronger claim to be protecting a zone of activity that serves the aims of justice itself — coercing people into relations of less oppressive social cooperation. Simply put, to argue for the right to strike is to prioritize democratic freedoms over property rights.

Which Side Are You On?

Skeptics might still object that the right to strike is the wrong answer to the facts of oppression. Isn’t the proper response to push for altogether different social policies — like a universal basic income, workplace democracy, and socialized means of production — that would eliminate oppression? Why bother with the chaos and collateral injustice that strikes often unleash?

The short answer is that this is a non sequitur. The question for us is, “Given the facts of oppression, what may those who suffer it do to resist it?” It does no good to ask, instead, “What would the ideal, or at least reasonably just, society look like?” The latter is its own question, but as a response to our question it is unacceptably quietist. It verges on arguing that those who are oppressed must suffer until utopia becomes possible. And anyhow, utopia only becomes possible when the many have taken it upon themselves to exercise their own collective power to demand that utopia.

One might also object that it sounds like I am saying there are no restraints on what strikers may do. I am not saying that either. My point is to explain why a specific set of coercive strike tactics, which have been the centerpiece of the strike repertoire whenever the majority of workers have had it in their mind to walk out, are not limited by the requirement to respect those economic liberties that they violate. There are all kinds of things strikers shouldn’t do just to win a strike. But that is a complex and separate problem of political ethics — and it is one that we can only tackle once we have first acknowledged the shortcomings of liberal capitalism and the prevailing political morality that surrounds it.

The stakes of all of this are high. If one does not agree that workers are generally justified in engaging in mass, disruptive, and unlawful activity as part of exercising the right to strike, then one is committed to arguing that the state is justified in violently suppressing strikes — a violence with a long and bloody history. Some might very well draw that latter conclusion. But they should be clear about which side they’re choosing.

Either workers are justified in resisting the use of legal violence to suppress their strikes, or the state is justified in violently suppressing coercive strike tactics. No amount of dressed-up rhetoric about liberty and justice for all can shroud that inescapable fact.