Bernie Gets Socialistic

A national job guarantee has opened radical horizons for the Left. We should fight for it — but the devil is in the details.

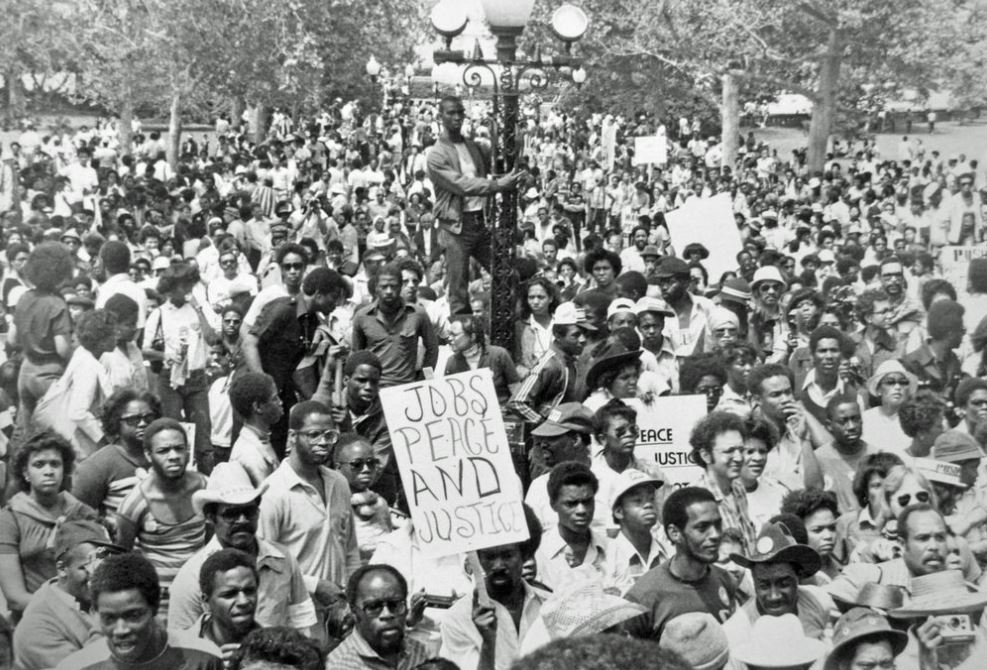

A march protesting high unemployment rates for African Americans on May 17, 1980 in Washington, DC. DC Public Library Washington Star Collection

For us older lefties, Senator Bernie Sanders’s identification with “democratic socialism” began as a mystery. There seemed to be little that distinguished his current platform from those of liberals past, such as Franklin D. Roosevelt or Lyndon B. Johnson — no hint of socialism’s traditional connotation of “nationalizing the means of production.” But now his advocacy of a job guarantee has opened more radical horizons.

It hardly seems necessary to recount the myriad benefits of full employment. Poverty and inequality are reduced, public-sector expenses are offset, child development is enhanced, the political and economic power of labor is augmented, mental health is supported.

Some claim that after an inordinately lengthy recovery from the Great Recession the United States has already achieved full employment. This delusion seems unique to Democratic moderates and centrists, such as Paul Krugman. The Trumpified Republican Party evinces an unending mania for limitless growth, while the Left, for its part, has produced ample analysis of remaining slack in the labor market.

In a nutshell, the low unemployment rate masks the plight of those who work fewer hours than they prefer to, those who have given up looking for work, and those who would prefer to work but face various constraints preventing them from doing so. Moreover, the denominator of all these employment ratios is limited to “non-institutionalized” persons, which excludes the incarcerated.

One upshot is that prevailing conceptions of “full employment,” founded on the official unemployment rate, are racist and gendered. They gloss over the failure of the economy to provide a place for minorities and women. For this reason, a job guarantee has salience for efforts to address the economic impact of racism.

In broad economic terms, any economy that maintains a reserve of idle labor is wasting resources. Especially for the United States, which still wallows in what J. K. Galbraith described as “private affluence and public squalor,” such resources could be put to a plethora of useful ends. There is also a racial angle here — neighborhoods chronically short of public services could benefit from an expansion of infrastructure facilitating housing, transportation, education, and recreation.

Critics Left and Right

Objections to a job guarantee can be found at all points on the political spectrum. The Right’s hostility stems from its opposition to the public sector in general; its most frequent objection is on grounds of cost. But the prospective costs are typically invoked without parallel consideration of benefits, which are legion. The potential size of such a program is also attacked — but of course if big benefits outstrip big costs then size should not be an issue.

More interesting is the observation that a job guarantee effectively increases the minimum wage, or labor standards generally (since job-guarantee jobs would provide health insurance and other benefits). In this sense the public sector would seriously compete with the private sector for labor, increasing employer costs. They say this like it’s a bad thing.

From the perspective of working-class interests — and disproportionately for minorities and women — such competition is a feature, not a bug. One historic benefit of public-sector employment has been to fortify labor standards in the private sector. Moreover, research on the minimum wage suggests that a higher floor on pay generates knock-on effects that ripple through the higher percentiles of the wage distribution. We might also note the positive macroeconomic impact of a downward redistribution of income.

At their most agitated, critics characterize such an impact as “nationalizing the labor market.” Raise your hand if you think this isn’t terrible. I return to this crucial angle below.

From the Left, one baffling criticism comes from my notorious friend Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Institute, who characterizes a job guarantee — and by implication public employment in general — as workfare, or in more arcane terms, “unemployment benefits with an activation requirement.”

Workfare, unemployment insurance, and public assistance programs are all designed to encourage beneficiaries to find private-sector work by making participation less appealing than a real job. The presumption that a job guarantee would be like workfare — despite the fact that the current proposals call for decently paid, full-time work with benefits — implies a certain expectation of the political environment in which the guarantee would be implemented. The degree of political clairvoyance implied here is unpersuasive. Perhaps just as important is the social connotation of steady work, as opposed to the stigmatized status of unemployment and especially welfare-identified workfare.In much of the intra-left debate, job guarantee proposals are pitted against the idea of a Universal Basic Income. But this issue hinges on what type of UBI one has in mind. Although UBI advocates tend to be indiscriminate in defining exactly what it would be, the original notion was a replay of the old idea of a “demogrant,” wherein every person fitting a broad category (e.g., citizens over age sixteen) would receive a fixed, unconditional cash transfer.

The right kind of UBI, however, is what used to be called a negative income tax. It would replace what remains of cash welfare, food stamps, and Supplemental Security Income (welfare for the indigent elderly and disabled) and would thus fill in the most egregious gap in the current patchwork of US income guarantees — namely, the exclusion of able-bodied adults with children.

Such a UBI would be a complement, rather than a substitute, for a job guarantee, because for a variety of reasons there will always be some people who won’t work. The option of a job guarantee thus provides a rationale for a residual UBI, and a UBI closes a gap in the universal guarantee of income that a job guarantee fails to cover. And we could speculate that in political terms, each program strengthens the other.

Implementation

To my way of thinking, the biggest gap in current job guarantee proposals pertains to their proposed delivery mechanism — namely, federal project grants to state and local governments. There are both technical and political difficulties in this approach which have yet to be addressed in job guarantee proposals, except in passing.

Most federal grants to states and localities are provided by formula: easily quantified characteristics of state or local jurisdictions are entered into a formula that spits out the recipient government’s grant allocation. The use of such formulas reduces the cost of administering the program for the grantor. But construction of the formula itself will be subject to all sorts of devious political machinations.

Project grants, by contrast, are bureaucracy-intensive. Criteria for awards must be specified. Aspiring grantees must devise proposals to apply for funds. Proposals must be reviewed by the grantor. The reviews themselves (say, by a Department of Transportation) are subject to oversight by the Congress. Rejected applications will be disputed by the applicant, and those disputes will be subject to review, and so on. The more the rules are modified to address assorted criticisms, the more opaque the entire process becomes. Incidentally, governments with higher-income constituents will be able to play this game with more skill than those representing poorer communities.

Meanwhile, state and local governments — and their taxpaying constituents — will prefer to direct job guarantee resources to services they already provide. This is an objection that public-sector unions have raised in the past. It’s not enough to say we won’t let them do it: the armies of the state-local sector vastly outnumber those of the federal government. The states can practice the political equivalent of asymmetric warfare.

Thus far I’ve presumed good intentions all around. But of course, state and local governments in all regions of the United States are full of deplorables. And including local community participation is not much compensation, since the construction of such community entities will be subject to the same flaws as the local governments themselves — if, indeed, they’re not under the de facto control of those governments. All things considered, I’d say the delivery mechanism in current proposals requires elaboration.

Freedom National

The alternative to decentralized delivery is to bypass state and local governments altogether. The federal government can erect state enterprises across the country to perform useful tasks routinely neglected by the states as well as by the private sector. A common feature of such tasks is that their benefits tend to be spread over multiple jurisdictions, thereby reducing the incentive for any individual state or local government to undertake them. Nostrums of fiscal austerity have been blocking them for decades, so there is no lack of such tasks. They include:

- Large-scale infrastructure projects. Such projects are too large to be financed by existing federal grants, which tend to spread money around thinly. Big-ticket items are usually financed by earmarks, or not at all. A national infrastructure bank could devise and assign such projects to regional public enterprises.

- Climate change. Rebuilding coastlines, reclaiming land damaged by industry and mining

- A national electric grid

- Public broadband

- School repair

Everybody can think of things to add. The key criterion should be work that is not normally undertaken by state and local governments — work which they don’t particularly want to do.

A network of federal, public enterprises would not be immune to the pressures faced by a more decentralized program, but it might be less vulnerable. A precedent can be found in the original War on Poverty, which created parallel institutions of local government, called Community Action Programs, that constituted independent bases of political power. Within a few short years, established local governments succeeded in destroying this replay of Reconstruction; it was a threat to local political elites. That doesn’t mean it isn’t worth proposing, quite the contrary. The struggle continues.

The resources of these enterprises would be made to expand or contract with the business cycle, just as private-sector firms grow and shrink with even greater volatility. The enterprises would provide real jobs, subject to the same labor standards of large private sector firms, and for that reason enjoy equal social status.

Perhaps it’s my ego talking here, but an understanding of fiscal federalism — my own field of expertise — seems to be absent on the left. People seem to think the state-local sector is a genie that can be summoned at will and will always say “Your wish is my command.” The reality is that it is very difficult to prevent the states from doing what they want with federal money, and it won’t be what you want them to do.

Delivery mechanism aside, there is nothing fantastical about the federal government hiring people. It can hire more when the private sector hires fewer, and vice versa. It isn’t economic rocket science.

The primary distinction I want to make here is that a job guarantee in the form of new public enterprises is indeed a nationalization of part of the labor market, and in the process provides critical public services and facilities that would otherwise not be forthcoming, on a permanent basis. Such output directly augments the public sector, providing public consumption and investment. This is the future that liberals should want.

There is no need to be deterred by the fact that some current proposals involve high estimates of pay for the new public jobs — numbers that imply a very sharp disruption of the bottom half of the US labor market. What matters is not the notion of an ideal program, but a practical schedule of progressive advances in labor standards that will force the private sector to keep up. In the process, we could expect parallel growth in unionization and the overall political power of the working class. The country would end up looking very different.

I would suggest that this way lies democratic socialism. Thanks, Bernie.