John Dewey’s Experiments in Democratic Socialism

John Dewey is commonly seen as the liberal philosopher par excellence. But his staunch commitment to democracy put him on a collision course with capitalism.

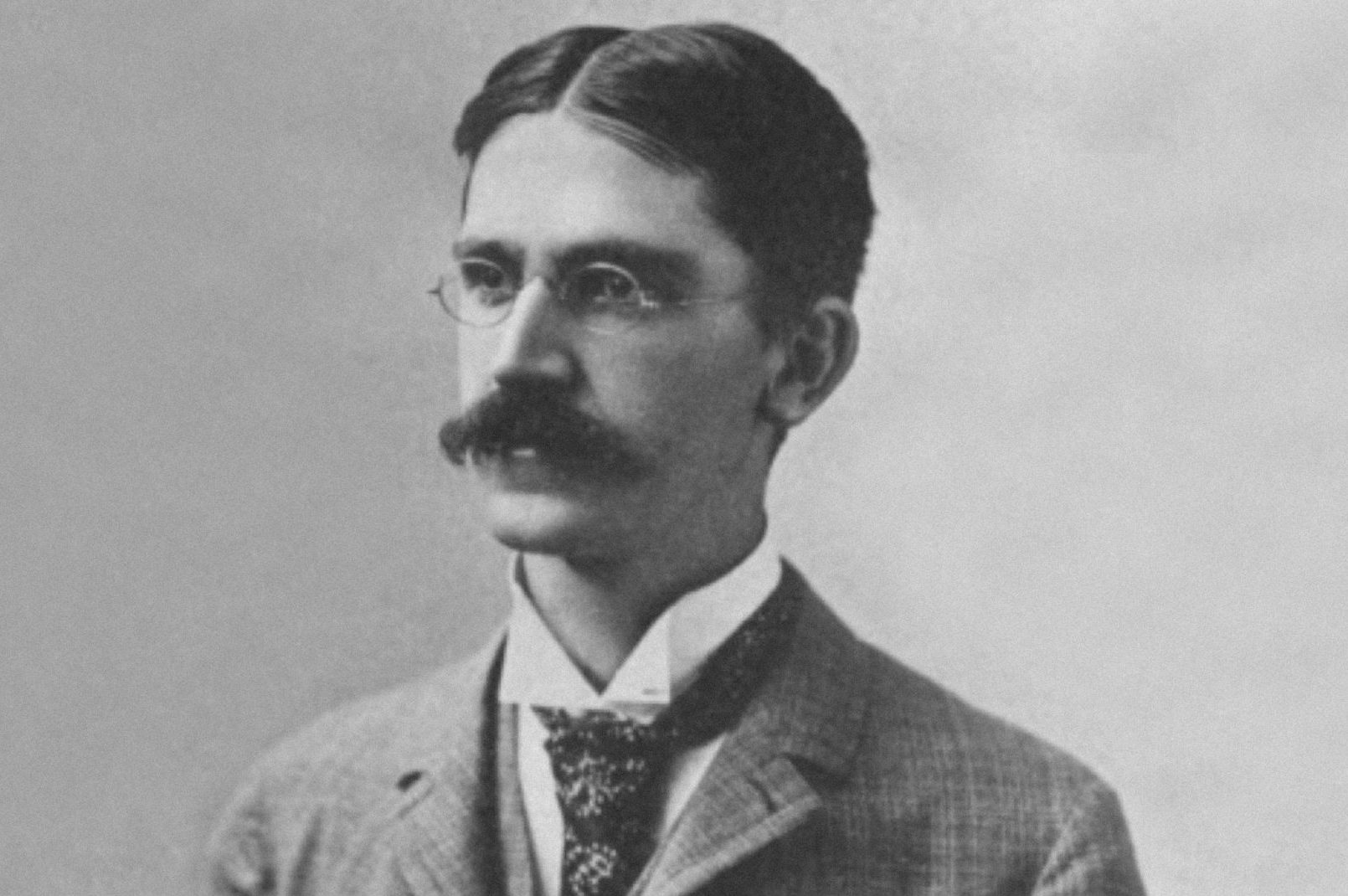

John Dewey as a young professor of philosophy and psychology at Michigan, 1891.

“If radicalism be defined as perception of need for radical change,” the American philosopher John Dewey wrote in his 1935 book Liberalism and Social Action, “then today any liberalism which is not also radicalism is irrelevant and doomed.”

Over the course of a lifetime that stretched from the Civil War to the Cold War, Dewey pushed liberal commitments to freedom of inquiry, equal opportunity, and personal liberty to their democratic limits. Realizing that equal liberty for all required democratizing institutions from the state to the workplace and the school, Dewey set his radical liberalism on a collision course with the capitalist social relations that liberalism historically served.

While the Vermont product became one of the twentieth century’s most well-known philosophers, widely considered the philosopher of American democracy itself, his idiosyncratic thought earned him enemies across the political spectrum. The Right saw him as a Communist, the Communist Party saw him as a philosopher of reaction. As for Dewey, the only “ism” he could attach his name to was “experimentalism.”

Dewey’s experimentalism, or “pragmatism” as he often called it, has long been viewed with suspicion by many leftists, who see its aversion to far-reaching theories as a precursor to Cold War liberalism’s proclamations of “the end of ideology.” Yet revisiting Dewey’s decades-long attempt to renovate liberalism from within reveals a more complicated story.

In radicalizing liberalism, Dewey ended up formulating a democratic socialism that strove to expand workers’ control over the social forces that shaped their lives. And that, he had no trouble admitting, required confronting capitalism.

Dewey’s Political Education

John Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont on October 20, 1859, just days after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry sent shock waves through the nation. The foundations of Dewey’s political thought are often traced back to his experience of civic life in his hometown, or the reformism of Vermont Congregationalism, but no source was more influential than his encounter with the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel as a student at the University of Vermont.

After a short stint as a teacher in Oil City, Pennsylvania, Dewey entered graduate school at Johns Hopkins University in 1882 and immersed himself in the German idealism that dominated Anglo-American philosophy at the time. Dewey graduated two years later and begin his career as a prominent voice of idealism, first as a professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan and then the University of Minnesota.

In those early years, Dewey formulated three ideas that would come to define his mature vision of democracy: individualism offers a distorted vision of human freedom, genuine freedom is found in social cooperation, and true social freedom is impossible in a class society.

Dewey’s abstract ruminations on freedom began to take concrete form in 1894 when he accepted a teaching position at the University of Chicago. Dewey’s years in Chicago are remembered primarily for their contribution to democratic pedagogy and his argument that schools in a democratic society should become environments where students collaboratively develop their capacities rather than institutions inculcating a fixed body of knowledge. But they also marked his first real engagement with the labor movement.

In the spring of 1894, workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company launched a wildcat strike to protest wage reductions, and a nationwide solidarity strike brought rail travel through continental hubs like Chicago to a grinding halt. A quarter-million workers were in revolt. Federal and state government responded to the mass action with violent suppression. In Chicago alone, fourteen thousand federal troops, state militiamen, and private marshals descended on the city to reclaim the yards. Before it was all said and done, thirty strikers lay dead, the nation’s most powerful railroad union had been crushed, and its president, Eugene Debs, was in prison on federal charges.

From his jail cell, Debs described the strike as a tragically necessary lesson for the public in the perils of “the money power” and a clear demonstration of the need for a labor party that could protect workers from “corporate anarchism.” Dewey, arriving in Chicago just as the strike began, saw it much the same way. He wagered that the labor battle might revitalize the party system and spark public debate about the tensions between capitalism and democracy at the heart of American society. “I think the few freight cars burned up is a pretty cheap price to pay,” Dewey wrote. “It was the stimulus to direct attention, and it might easily have taken more to get the social organism thinking.” Not unlike the democratic school, the labor struggle offered a space for self-creation and the development of a genuine social consciousness.

The lessons of the Pullman strike stuck with Dewey. A radicalizing experience for the young philosopher, it dramatically illustrated the shortcomings of a nineteenth-century liberalism in a twentieth-century industrial society. More than twenty years later, he would argue that the right to strike — a vital new freedom in this industrial age — demanded a novel conception of liberty that was incompatible with traditional liberal notions of free contract. When Dewey acknowledged that “our present methods of capitalistic production” reduce liberty because they “are so coercive” for labor, he was arguing that this made capitalism itself illiberal — it impedes the ability of individuals to develop freely through their social activity with others. Voluntary contracts are a farce when the choice is work or starve.

The same year, in his celebrated 1916 book Democracy and Education, Dewey repeated the point, arguing that wage dependence constituted an “illiberal” defect of capitalist societies. By subordinating the ends of productive activity to the profit interest of employers, wage labor prevented workers from cooperatively defining the meaning and direction of their collective activity. “The activity,” he wrote in characteristically clunky prose, “is not free because not freely participated in.” This profound contradiction — professions of liberty in the abstract, support for coercive contracts in reality — underlined the need to reconstruct freedom as both an idea and a practice.

For Dewey, unions and strikes were not simply devices for increasing workers’ share of the social surplus or allowing them to realize private liberty off the job. The labor movement embodied a democratic path toward a new kind of social order where the competitive struggle to amass power and wealth would be replaced by the cooperative collective action of equals. Against the social Darwinism of the market, Dewey embraced a democratic, egalitarian Darwinism that emphasized the open and unscripted nature of the future and the freedom of people to exercise cooperative control over their world.

The path to social evolution, he argued in The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy (1909), lies in developing human beings’ capacities for social cooperation rather than a struggle for the survival of the fittest. And because democracy bases its legitimacy on the widest possible social interest, democratic politics became both the means and end of Dewey’s vision of free and equal human development.

Progressivism, Localism, and Third Party Politics

Democracy in theory and practice became ever more dialectically entwined during Dewey’s years at Columbia University (1905-1930). In New York, Dewey rose to national prominence as an influential philosophical voice of the Progressive Movement. From his writings on women’s suffrage, his role in establishing the American Civil Liberties Union in response to wartime repression, and his criticism of the New Deal’s deflection of more radical possibilities, Dewey’s writings and actions thrust him again and again into the center of national debates.

Dewey offered the fullest statement of his vision of democracy during these years in his 1927 book The Public and its Problems. Modernization had unleashed economic and social processes that at once bound Americans in new forms of interdependence and reduced individuals’ capacity to master the forces shaping their lives. The rise of a “Great Society” had swept away the agrarian and localist arrangements underpinning American republicanism. While some technocratic progressives thought that these transformations demanded new forms of elite control, Dewey made the case that they simply called for a new conception of “the public,” one that could democratically shape the potential that had been released.

The public, Dewey reasoned, is a collective called forth by the experience of common problems. If it can grasp its problems, the public might wield its political power to manage them. Yet for the public to discover itself as a political agent, the interdependence that ties individuals and communities together needed to be made transparent — the meaning of these new social relations must become integrated into the public’s shared intelligence.

This process required the social basis of public life in local communities to be renewed. Everyday spaces of social interaction — the household, the street corner, the workplace, the tavern — had to become the foundation for a “Great Community” from which the public could ultimately grasp the social whole. Democratic encounters in these spaces could help individuals recognize their place within a social whole, a critical consciousness that Dewey thought could only be rooted in everyday experience. “The local,” he wrote, “is the only universal.”

But renewing local democracy demanded a national political presence. In the years following the Depression, Dewey worked to develop an alliance of progressive forces — from middle-class reformers to socialists in the labor movement — that could launch a third-party challenge to the plutocratic political system. In 1929, Dewey had become both president of the People’s Lobby (formerly the Anti-Monopoly League) and national chairman of the League for Independent Political Action (LIPA). The two groups sought to unite liberals and socialists behind a common program of industrial democracy.

LIPA’s support for progressive taxation, the nationalization of key industries, banking reform, the abolition of the Espionage Act, protection of civil liberties, state investment in unemployment and health insurance, and anti-lynching laws led it to endorse Socialist Party candidates. But it never fully embraced socialism as a motivating economic philosophy, despite the role of socialists like Norman Thomas, A.J. Muste, W.E.B. Du Bois, and James H. Maurer within the League. Instead, its chairman prioritized immediate political tasks. Dewey focused on pressing for reforms that would shift the balance of class power and make it possible to introduce democracy into industrial life.

The experiment in third-party politics was short lived. Dewey’s insistence on a big tent often placed him in conflicts with those to his left. Many committed socialists broke away from the League when Dewey attempted to attract progressive defectors from the Republican Party, moving on to concentrate on building a mass workers party from the ground up. The clash of experimental evolutionism and revolutionary urgency was one of many that would mark Dewey’s relationship with American socialism over his career.

Marxism and Class Struggle

Despite their shared dialectical sensibilities, critiques of classical liberalism as class ideology, and vision of emancipatory social transformation, Dewey never pursued a serious study of Marx. According to the radical writer-cum-conservative critic Max Eastman, Dewey even confessed in 1941 to having never read Marx despite much evidence to the contrary. But if Dewey did not take a keen interest in Marx, his pragmatism found itself at odds with American Marxism throughout the 1930s.

This isn’t to say Dewey was the fierce anti-communist of liberals’ imagination. As his 1928 book Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World reveals, Dewey held out hope for the Bolshevik experiment and particularly admired its educational reforms. The revolutionary changes in Russian society, he wrote, represented “a release of human powers on such an unprecedented scale that it is of incalculable significance not only for that country, but for the world.” He lamented that the United States — with its mature industrial stock and advanced system of public education — could not undertake similar experiments without a comparable experience of revolutionary civil war.

At the same time, Dewey worried that the revolution’s democratic potentials were at risk of being squelched by the hardening ideology of state communism. Fixing the ends of this experiment in liberty risked imposing “a frost” that would chill the creative energies the revolution had unleashed. He alleged that “the more successful are the efforts to create a new morality of a cooperative social type, the more dubious is the nature of the goal that will be attained.” If socialism was to have democratic meaning, it needed to be given shape through the collective experimentation of a democratic polity — even when these experiments deviated from theoretical expectations.

Dewey’s exchange with Leon Trotsky the following decade illustrated this distinction between experimental and ideological socialisms. Dewey was invited to serve as chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials, better known as the Dewey Commission. Dewey, Trotsky, and a group of international liberals and socialists met in Coyoacán, Mexico for a week in the winter of 1937 to weigh the treason charges leveled against Trotsky and his son by Soviet courts.

Dewey and Trotsky had little time to speak in depth about political philosophy at the trial, but an opportunity arose the following year when the New International asked Dewey to contribute a critical response to Trotsky’s indictment of liberal moralism, “Their Morals and Ours.”

Dewey agreed with Trotsky on a few important points. Trotsky’s denunciation of liberal hand-wringing about revolutionary violence as an exercise in bourgeois ideology rang true to him. The two also agreed that the question of means and ends had to be dealt with in dialectical, rather than absolutist, terms.

But from here, the pair departed. From Dewey’s pragmatist perspective, only ends, understood as practical consequences, could justify or prohibit the means. Class struggle, then, may prove to be a justified means toward the end of radically reconstructing American democracy. But this conclusion could not be derived in a scientific fashion from the iron laws of history; the success of the class struggle in formulating and realizing its ends was a practical question to be worked out experimentally by workers themselves. Trotsky’s critique of liberal absolutism, with its appeal to scientific necessity, merely set up another absolutism.

The conclusion Dewey drew from this high-profile exchange represented the core of his own democratic socialism: democratic ends demand democratic means. No participatory future of mutual social cooperation is possible if it demands suspending democratic values in the present.

“There is comparatively little difference amongst the groups on the Left as to the social ends to be reached,” he argued in a 1937 essay, “Democracy is Radical.” “There is a great deal of difference as to the means by which these ends should be reached and by which they can be reached. The difference as to means is the tragedy of democracy in the world today.”

Democracy Is Radical

By the time he died in 1952 at the age of ninety-two, both Dewey and his philosophy of pragmatism had been conscripted into the service of Cold War liberalism. Pragmatism’s criticism of socialist dogmatism had become synonymous with the anti-dogmatic dogmatism of liberal attacks on “totalitarianism” — certainly its own kind of frost on creative political energies. It was this legacy that came to define pragmatism, particularly as it was recuperated by Richard Rorty and others.

But it’s hard to read this 1935 quote from Dewey and see a garden-variety liberal:

the ends which liberalism has always promoted can be attained only as control of the means of production and distribution is taken out of the hands of individuals who exercise powers created socially for narrow individual interests. The ends remain valid. But the means of attaining them demand a radical change in economic institutions and the political arrangements based on them. These changes are necessary in order that social control of forces and agencies socially created may accrue to the liberation of all individuals associated together in the great undertaking of building a life that expresses and promotes human liberty.

Like other democratic socialists, Dewey maintained that American society was profoundly undemocratic, and that rectifying this injustice was only possible through democratic means. The school, the union hall, and the people’s party could all be sites of popular empowerment and worker control where an emancipatory future could be built in the present.

While Dewey certainly faltered at times — his support for World War I, for instance, was an unqualified black mark on his record — his radical liberalism was not a defense of the status quo; it was an experiment in transforming the liberal tradition from within, a commitment to pushing toward a society that recognized liberty as an empty word without cooperative self-rule.