Free Speech as Battleground

Censorship used against our enemies will soon be used against us.

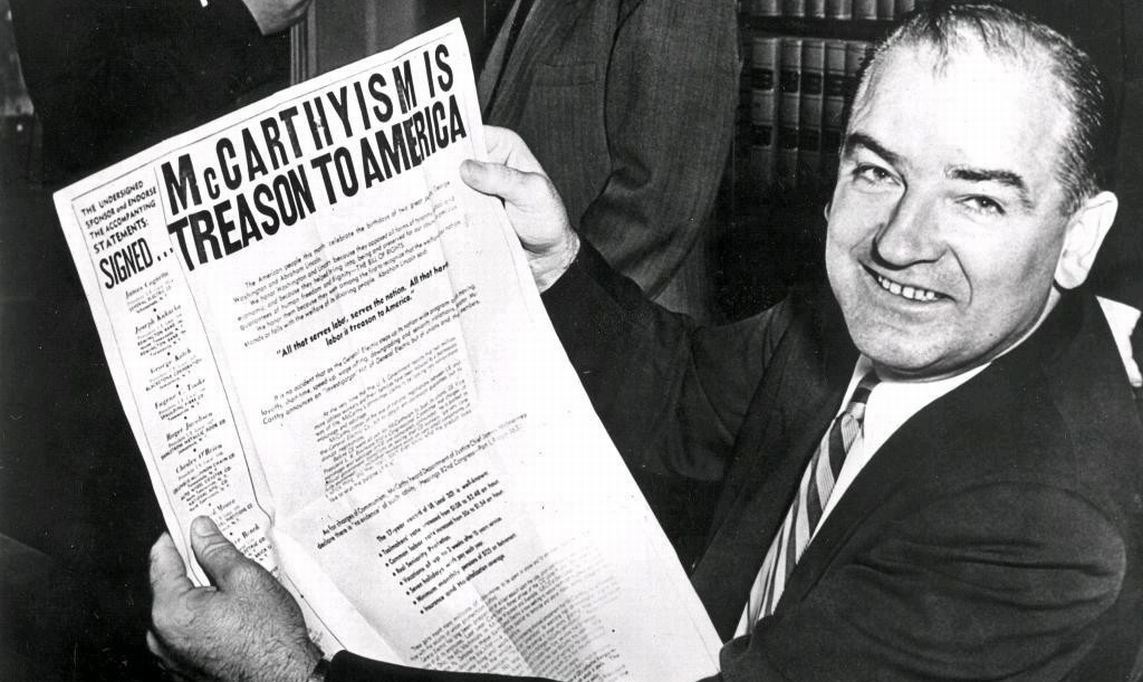

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), smiling for the camera, displays a newspaper advertisement that proclaims "McCarthyism is Treason to America." Wikimedia / Hulton Archive

You have to give the political right credit. In recent months, they have, Judo-style, baited the campus left into bumptious overreactions that have seen student activists at Middlebury, UC Berkeley, and a few other places calling on university administrations to shut down — that is, censor — vile speakers like Milo Yiannopoulos and Charles Murray.

Students and faculty are absolutely correct to challenge reactionary speakers. But they should never ask for censorship. This might seem like a minor or technical point; it is not.

Censorship used against our enemies will soon be used against us. The Left will never win the battle of ideas by trying to suppress opposing arguments. The only way to win is by a concerted, long-term effort to out-argue, out-educate, and out-organize the Right.

To be clear, we are not making a moral argument. We are not saying that racist and reactionary ideas are worth hearing — they are not. Rather, our point is purely strategic.

Asking for censorship makes the Left appear narrow-minded and afraid. And it opens the door for censorship to be used against us. Lest one think that last concern is an abstraction, recall that in January Fordham University denied Students for Justice in Palestine the right to operate on campus because the group’s work “leads to polarization.”

The strategic way to frame left opposition to offensive right-wing speakers is with more speech. Use free speech to drown them out, and more importantly, expose them for what they are. Fight speech with speech. Slogans like “free speech against hate speech” are better than “free Milo from ever speaking again.”

What then is the line on hate speech? It would seem that direct threats against actual people on campus — frat boys being encouraged to physically attack whomever — crosses the legal line into “fighting words” which are defined as personal threats or insults addressed to a specific person that are likely to start immediate violence.

Fighting words are not a legally protected form of speech. Yiannopoulos’ threats to out undocumented students, or his habit of calling out individual trans or feminist students, often leading to his followers threatening and bullying them, would seem to qualify as fighting words.

Other than that, it is our job to crowd out and out-speak the Right, but never to demand that the university do it for us. Censorship is a slippery slope, and the next offensive speaker censored might just be you.

As regards free speech, the Left needs to know and teach its own proud history.

While the annals of extending free speech in America have included a few pioneering journalists and obscene artists, what is more striking is the large number of feminists, anarchists, communists, and socialists who show up in the story.

The Right is part of this history as well, but almost always on the side of censorship. In the nineteenth century, they appear as the southern Slave Power in the House of Representatives passing the gag rules that automatically killed discussion of abolitionist bills; and as the South Carolina Attorney General indicting northern abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, for using the US postal system to send abolitionist literature into the South.

Later, the Right also shows up within the state and municipal governments that repressed and censored labor organizers, suffragettes, and pacifists. And in the mid-twentieth century, the Right are the federal authorities who used the Smith Act of 1940, which made it illegal to advocate overthrowing the US government, to imprison the African American politician and communist Ben Davis and deport the radical labor leader Harry Bridges.

Into the early twentieth century, First Amendment rights were often interpreted as applying only to a person’s relationship with the federal government. States and cities, it was held, retained the power to suppress speech, usually left-wing speech.

The struggle for free speech was most often entwined with broader labor struggles. Thus, in 1893, when Emma Goldman encouraged hungry workers onto the streets, she was arrested. Defending herself on the grounds of free speech, Goldman lost and did eight months in jail.

In 1909, the Industrial Workers of the World began what would become a multi-year, nationwide campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience against local ordinances suppressing free speech.

Starting in Spokane, Washington, Wobbly activists violated local censorship laws at public rallies, filling the jails with hundreds of prisoners at a time until the local press and even mainstream liberal civic groups had to rally to the Wobblies’ cause.

All along, the Right and capital fought back, using the state to suppress speech. The Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918 were created for these purposes. In 1917, Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs was convicted under the Espionage Act for speaking against the First World War and was sentenced to ten years in prison. It was from these struggles that the American Civil Liberties Union emerged in 1920.

Only in 1925 were First Amendment rights affirmed as applying to the states. The case was Gitlow v. People of New York, in which Mr. Gitlow was convicted of “criminal anarchy” for distributing a tract called “the Leftwing Manifesto.”

In 1931, the Supreme Court finally extended speech rights to nonverbal symbols like flags in the case Stromberg v. California. Again, the hero was a leftist, the nineteen-year-old Ms. Yetta Stromberg of the Young Communist League. Her crime had been to violate California’s “red flag law,” which prohibited the display of a red flag as “an emblem of opposition to the United States Government.”

The extension of free speech to universities was famously championed by the UC Berkeley Free Speech movement, which emerged to defend left-wing students who wanted to distribute radical literature and make radical speeches on campus. Winning that fight came at the price of students being beaten and jailed.

How could we have taken the enemy’s bait and called for censorship? No doubt it appeared to some activists as merely a responsible first step. In other struggles, that makes perfect sense. For example, students calling for divestment from fossil fuels first request divestment — that is, open negotiations with the administration — and when rejected they move on to disruptive protest.

But there is a more troubling side to this as well. Let’s face it, on some elite college campuses, the student activists are obsessed with symbolic gestures and the rigorous policing of language. One recalls the Oberlin students who in 2015 denounced their cafeteria for “cultural appropriation” when serving underwhelming versions of Banh Mi and General Tso’s chicken.

The campus left’s hypersensitivity to language has provided the Right with an opening. While many far-right ideas sound patently insane to the average person — for example, that the United Nations has secretly occupied the US and patrols the skies with black helicopters — the Right’s jabs at campus culture are not so easily dismissed.

The Right is in the process of running a damn good play: baiting the Left into an embrace of censorship and thereby robbing one of the Left’s great cultural prizes, the morally sacrosanct banner of “Free Speech.” We cannot allow that.