Party and Ministry

Syriza Minister of Education and Culture Aristides Baltas on the tensions and challenges of working within the Greek state.

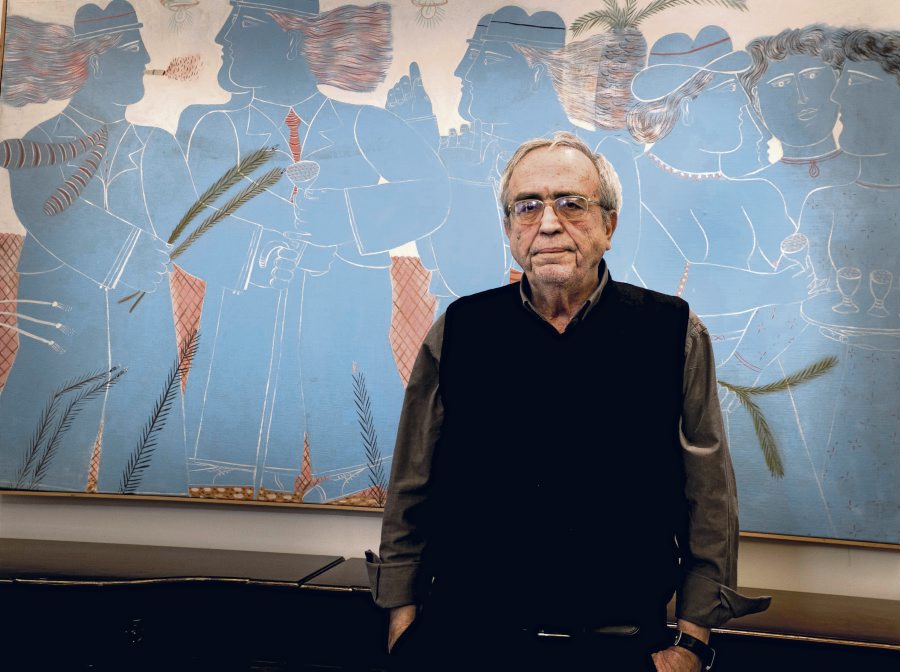

Aristides Baltas in Athens. Stefania Mizara

- Interview by

- Leo Panitch

When the new Greek government was formed shortly after Syriza’s historic electoral victory of January 25, 2015, Aristides Baltas, the eminent Greek philosopher, was appointed to head the largest department in the state, with responsibility for administering not only education as well as cultural and religious affairs, but also sport.

As a longstanding leading member of Syriza’s central committee, Baltas had played a key role in coordinating the policy program on the basis of which Syriza made its sudden political breakthrough three years earlier. In an interview Leo Panitch conducted with Baltas shortly before the June 2012 election, Baltas had expressed his concern that very few of even the most politically able active members in the party had “ever thought of how to run a ministry.”

Moreover, he also feared that to try to change the corrupt and clientelist Greek state would not only be an enormously difficult task for which Syriza was not really ready in 2012, but that drawing in the most able people in the party to do this might also leave Syriza bereft of its most able cadre just when it needed them most.

These questions were taken up again in these excerpts from the interview Leo Panitch conducted with Aristedes Baltas in Athens on May 14, 2015, probing his experience during the first few months inside the Greek state.

At the beginning of our previous interview in 2012, you quoted the Spanish poet Machado saying, “don’t ask what the road is; you make the road while you walk it,” so as to capture the adventure Syriza had embarked on in its quest to transform the Greek state. So now that Syriza has entered the state, and now that you are the minister of the largest department in that state, do you not feel like you might have entered a labyrinth?

The road is uphill, for sure. But it’s not a labyrinth, I think. It’s full of obstacles, some of them expected, some of them not. New vistas, in a way, have opened which were not imagined before, in the sense that the view from below, if you like, from the point of view of the movement or the party (and this would be so even with a perfect program) is very, very different from the view from above, from the place of the ministers, so to speak.

And it’s impossible, I find, to have a premonition of the kind of view you actually have by being up here. There are all kinds of new questions which were not addressed before, not even thought of before, areas of responsibility not known before, obstacles not really understood before, and yet possibilities, also, not understood before.

The very notion of political time is very different up here. You have to make decisions on the spur of the moment almost literally. You don’t know the consequences correctly. You don’t know even if the initial answer to an immediate question is correct or not, but you nevertheless have to quickly take it.

On the other hand, once you are looking from above, you cannot understand how people from below, so to speak, from the party, see things, how not being part of this thing, can make them so impatient. You cannot understand, because the very notion of time is very different.

In terms of now occupying such a position inside the state, you also said near the beginning of our previous interview that the Greek state — and you were stressing the distinctive history of Greece in this respect — is “absolutely corrupt, beyond possible measure corrupt.” Now that you’re inside, was this is an exaggeration? Or is it true?

That’s a very good question. I would take back the word absolutely for various reasons, which is in itself an exaggeration. Because you find also in this state, certainly in this ministry, treasures of generosity or self-effacement in view of something bigger.

I found people here ready to sacrifice many hours without pay to help me find my way around, people whose talents were concealed, shoveled down, because the previous governments could not use them. And without this, you couldn’t do anything.

It also requires historical qualification. We had a society in 1821, when the revolution broke out, which was under Ottoman rule and organized locally through clans, extended families, and things like that. Many of the people who made up the revolution didn’t know anything about the Enlightenment or things like that. This came from the outside.

But when the revolution was finished, I mean, not really won, but not lost, you had a state structure imposed upon it which was based on the then dominant forms of state. This, together with a Bavarian bureaucracy, which came together with that new state, conflicted with what people knew, were conversant with, understood of themselves or society, and produced a sense that they could not really enter in what was for them a new kind of structure.

So you have a congenital divide, a congenital mistrust, from the very birth of that state. During the two centuries since, instead of political parties at power to break this kind of mistrust, they heightened it, and also added all kinds of clientelistic networks. With each new government a new superstructure was imposed over the old ones, so that a pyramid of such structures upon structures was built.

For instance, when we came in, we found that bidding processes for contracts from the ministry were under way. And as we tried to rationalize them, requests for interviews with me suddenly started coming in from some businessmen. As the ministry responsible for sports, we passed legislation to clean up betting on sports matches. During this process, black limos drove up here dispensing owners of football clubs who had to be told they could not bring the guns they were bearing into the building.

These are mere examples. A deeper symptom of the structure of corruption is that someone who has worked hard on a brief which is ready to go up to the next level for approval might put a €50 bill in the file in the hope that this might ensure it would be not neglected!

You arrive at a point when you don’t know where to start to do something about the whole structure. When you break, or try to break one structure, there’s another below, and this ad infinitum. So this is, let’s say, the site, the structural site, of corruption related to all the clientelistic networks.

But it is also, to be frank, related to how ordinary people are so very used to approaching the state to solve their problems. You have people with tragic histories and tragic problems who don’t know how to enter the state, to try to solve their problems through the institutional channels — or because the institutions throw their problems away. So what they do is bypass the institutions to reach the minister. The minister likes that, because this way he gets votes. And so this whole structure has in-depth effects on mentalities.

Even those of us who have always stood against this kind of thing, when we have a problem, the first question is whom do you know, not how to solve the problem. Whom do you know? We do it ourselves. So if you don’t accept this for yourself, you cannot address people and say from above, like the rationalists would try to do, oh, this is all bad, follow the rules. And this continues the mistrust. What we have to break is the mentalities. But this breaking of mentality starts from above; if you are to be frank start with yourself. And, of course, this is a long term procedure.

There is the question of whether to destroy the state or rationalize it. This seems to be the wrong question. On the one hand, you cannot rationalize this kind of state. On the other hand, rather than destruction we need a different word. What I would prefer, based on my experience in these few months, is to say: open up the state. For example, we have a big hall downstairs, and when schools arrive for different events I go down to address the students and teachers, and this is a breath of fresh air.

This is new?

The previous minister had a whole guard around him and all kinds of security items. I dispensed with this, and when I first stepped out of the office on my own to walk around the place, the secretary told me, please have some ether with you, because people will start fainting, seeing a minister walking the corridor. And now this has become habit, and everybody smiles when I come in.

This is part of opening up the ministry to the outside, to plain sight. But this applies vice versa, which is more important, I think. I try to visit schools, as far as time allows, and go to class, literally, without a camera, without anything, just telling the director of the school I will be coming tomorrow, so don’t be surprised.

And so this gives you the idea that instead of destroying or rationalizing, you just open it up. And if you do this continuously and systematically, then this isolated, self-enclosed big building representing the state, with people waiting in queues to put their paper in, etc., becomes instead something much more friendly. And if this develops from the outside now as a kind of movement in relation with the state, then you can start thinking more from the point of view of how the state might start to wither away.

That too is an exaggeration.

Of course it is. All this depends on movements in society which we cannot foretell. To be more specific, I am thinking not so much of movements of teachers, in the sense of teachers’ unions, or of a syndicate of parents, but of movements centered around schools, taking into account teachers, students, parents, the whole of the society centered around the school and in relation to the corresponding problems of this part of society.

If this kind of thing starts to express itself as a new kind of agent, then this can push further such a withering away of the ministry and lead us to think about how this could become implemented in the state generally, and give us further ideas of how to go one step further in such withering away.

This is my experience after almost three months of “governing.”

Well in terms of changing and opening up the state in the ways you describe, how much are the people that you found inside the state who are not corrupt and are hard-working really sympathetic to this? And what about those you have drawn into the state since you formed the government? Are they oriented to opening up the state? Or are they mainly policy-oriented? And are they also so preoccupied by the crisis that opening up the state is not on their agenda? Are they so focused on the negotiations that what you raise in that respect is a sideshow?

Regarding such issues, we are relying on volunteers to make us understand who is who in the ministry, who is who in the kind of organs we are obliged to govern. And then we have the problem of finding the capable people who are ready to give all of their time to changing the situation.

Most important, however, and what is amazing to me, and I think that perhaps this is a new concept in the making here — is that what we witness now are immobile movements outside the state.

You have a society which does not express itself. It’s almost as if it were impossible to talk, because the whole public space, as seen in the newspapers and television stations, is almost absolutely covered by the discourse of our opponents. Second, you have all powers in the world against us in one way or another. And inside Greece you have all political parties, without exception, against us.

So how does the government continue to be in place and having, with the recent polls, 60 to 70 percent of public support? The only possibility, and this is what requires inventing a new concept, is a kind of movement which doesn’t move, a kind of movement which does not say anything. But the support is there all the same. And what people tell me, me personally on the street when they recognize me, or here and there, almost silently, almost whispering it, is: Don’t give up. We trust you.

It reminds me of periods in history where the situation was much worse. During German occupation, for example, the slogan was heard everywhere: the Left saved us from hunger. Here we are again.

And people understand this. It reflects their sense of dignity. And I see it more concretely when the teacher unions come to talk about things with me. I immediately tell them there’s no money, no possibility of raising wages, no possibility of hiring more people, etc. And what I propose instead is to discuss social relations, how you change your everyday life without money.

But why are they silent? Why are they immobile? When we spoke in 2012, you said what was distinctive about the conjuncture which brought Syriza to the doorstep of the state was the diverse local movements. It started with the student revolt, but it kept coming up, you said, even in small things — save a tree, don’t build a stadium, all these things we talked about. So why is everyone holding their breath now? Is it only the negotiations? Or is it themselves sensing how difficult it is to change the state, even when our friends are in? What is the reason for this immobile movement?

I think one of the reasons is that they don’t trust any institution, any party, any newspaper, any television station. And they all of a sudden see a government which opens doors, takes away barriers. People meet me on the street and say hello like I was a usual human being and not a minister. And they understand this, they feel it, and they say, please stay there. For example, in the first week of the government about 1,000 policemen — I don’t remember the exact number — were taken away from guarding the ministers and were returned to do their police work.

We have the smallest possible ministerial cars and no people surrounding us when we go to the market or go wherever. They look at us and say, what kind of minister are you? They feel it. And so they don’t think that we are there to take advantage of being in government. So when we tell them we don’t have any money, they understand it. They are not demanding more wages and things like that. They understand that they cannot ask for these things now.

But what about the limitations that this shows? Does this not show a limitation of these diverse local movements that we saw before? They were demanding more. They were saying we can’t live this way. But now if they are immobile, it seems everybody is waiting for you to act. So when you said to me in our previous interview what we need to do is promote — and I’m quoting — “the economy of needs rather than profits,” it’s as though people are waiting for you to bring it into being rather than take initiatives themselves. Of course, in terms of waiting for you to do things, the question arises, since you are embedded in the old state, whether the twelve good and capable secretaries you have found here, who don’t necessarily share your perspective on an economy of needs rather than profits, are prepared to help you in this respect. Where are the diverse local movements showing that they themselves have some creativity in creating this economy of needs?

There are two places I have seen it. The one is the solidarity networks that existed before and continue to get organized. The second is in art, in music, etc. I mean, all kinds of small groups have started to express themselves. Something is happening there, even if it is not visible in the standard public space, as exhibited in galleries or shown on the television stations. But if you go up and down the streets and if you go to small theaters, you see this kind of new hope arising, as it were.

But yes, overall, I think that everybody’s holding his or her breath for the negotiations, hoping to get the money when the economy improves. So for now they find it by themselves, by working, by sharing. So this is a way of creating new social relations. This kind of thing is happening within this immobile movement, but without this taking voice and expressing itself in a way that could be heard by people who just visit Greece, or even by us.

Well, that’s the problem. If it’s not visible by enough people in the constellation of the leadership who will make the ultimate decisions about what to do in the face of the intransigence you are facing in the negotiations, they may operate with the notion that there’s no way that the economy of needs rather than profits is really an option.

So this brings me, then, to the relationship with the party and the quality and the use of the party in this situation. I come back to the question of those you did bring in from the party — we talked about the danger of taking whatever talent there was away from the party. Are those you’ve taken away, do they become policy advisers in the narrow sense? Or are they part of the talent you need to change the state? Most of all, are there the cadres there to animate again the now immobile movements and facilitate their own creativity in terms of developing an economy of needs?

There’s a time lag here too in the sense that we have not yet understood the connection with party and government, with party and parliamentary group. We are making steps in that direction, but the general feeling of a large part of the party is still, so to speak, at the level of only offering criticisms in terms of why don’t you move further in this or that direction, why are you appointing that guy and not that guy, and things like that. So instead of helping, they don’t help.

So fairly early on I very consciously decided to literally cut off all relations to the party for a couple of months, because this was a new position, a new kind of job, and if I just kept my old relations with the party going, then I would receive advice in one direction, then more in another direction, yet none of the people giving advice understand what the job’s all about.

So I said, forget about this. I’ll do it by myself with a few volunteers around me, period. And after I start understanding what the job is, then, based on that experience, I will go back to the party and try to discuss.

We have arrived at the second stage. I am going a lot now to the party to discuss things, explaining my experience here and needing new people who want to take new jobs and things like that. And we’re at this stage right now. The party has started to wake up, so to speak. These kinds of discussions go better now than they used to two months ago, in the first period of the government.

But, still, there is a kind of time lag, reflecting impatience or mistrust in the air, so to speak. Of course, being enclosed in the ministry twelve hours per day, I don’t have the experience of what’s happening on the local organization of the party, of how the debate is going on.

Yet I trust people of the party at the grassroots level to have an idea of what to do. And I have been thinking that I should go, let’s say, to our local group, tell them about this kind of experience, and urge them to go to the schools, look at what’s happening to the schools, talk to the teachers. Make the school a kind of gathering ground after class for you and the local people to just be there, talk to each other, play a movie, understand how the neighborhood works. And take it from there.

And not only schools. Go to some other local working places, institutions, cultural centers, and try to talk to people about how to organize themselves on the basis of the economy of needs and on the basis of changing social relations, and in terms of what you need to do, what you want to do in order to achieve this within this neighborhood.

Of course, we need to appreciate the historical point that there has never been in Greece the tradition of organizing at the local level this way. Everything was politicized in the sense that you had to express yourself only through protests and elections, organizing for the next elections, and after the first elections, you had the second ones. All this happened before you could think of what you were actually doing in terms of society.

I have two final questions, which are more about you personally, or at least me trying to think about what if I was in your shoes. Since you were influenced by the Althusserian framework, now that you are inside and responsible for the deep structure of the state does your role in the state now confirm that we are all the bearers of structures, or that we are slotted into structures, and subjectivity doesn’t come very much into it?

In a sense, I continue to consider that we are bearers of structures in a way. I think that the criticism against Althusser on that was unfair at times, because if you look deeper, then you find the place for subjectivity in there. But since then I have read much more about these things. I don’t know if I would go so far as to call for the need for a theory of the subject, but I can see that something like this is missing in a way, that I would want to add to those “structures,” as you say.

Well, I don’t know if “add” is the right verb, but I would consider that in addition, so to speak, of being bearers of structures, we are bearers of multiple relations which form various identities, that these identities play roles, that these roles have to be understood in their own right, that agency is very important to understand, that if you go to the political level, for example, you can’t just stay with structures, because you have to take account of conjunctures, initiatives, totally unexpected events or encounters and things like that. You have to take account of the “practical” aspects of politics as they have been thought about from Machiavelli to Lenin, to Gramsci and beyond.

From my experience in the Poulantzas Institute as the intellectual and research arm of the party, so to speak, you could see two currents of international thought being brought together influencing Syriza. One I would call, if you talk of it at the academic level, political science, political economy, sociology, things like that, while the other would be humanities, history, theories of subjecthood, literary criticism.

Syriza has brought these trains of thought together. And so I find myself comfortable either talking to people like you who are, let’s say, in a way, more or less, on the first side, as well as talk with people from the other side, as it were, from Agamben to Butler. I find myself strangely comfortable with talking to both of these currents. And in my kind of work, as far as this has a bearing on what’s happening here, I think at times I’m inspired by one, or at times by the other, without being eclectic or without wanting to be eclectic.

So yes, we do need to think more about, let’s say, a social theory which would take into account the subject. Taking into account the subject also means psychoanalysis, work done in literary criticism, in history, in the humanities generally. I’m not talking about a super discipline, of course. I’m talking about ideas of one discipline going to the ideas of the other discipline, not to try to find the synthesis, but since we are talking politics, to try to find ways of enriching thought in both traditions.

And you personally are not feeling trapped in the structure, being the minister of the biggest ministry in the state, with all the vectors of the discipline involved in the various roles you need to play? You don’t feel you’re trapped in that?

No, I don’t feel that at all, but I do feel that in order not to succumb to the view imposed by the position I find myself in, I have to do much more than I’m doing right now toward the outside. If you look at the ministry from a distance, the ministry has done little things, which need to be multiplied and diversified. Like going to schools, visiting neighborhoods or even jails.

But if you look at the ministry at another level, there are things which could become better within the ministry, without, as you put it, “succumbing to structures”. So you have to take account of many sides, the subjective, the objective, the party, what we were saying before about movements, those working in the ministry and many more things in order to feel that you are doing your job in a more general sense.

Okay. One final question in this respect, which has to do with subjectivity in relation to the political party structure and your role within it. This is probably more important than your temporary role as a minister in the state, however long this will go on. Bukharin famously said, even in the face of death at Stalin’s most infamous show trial, that he had learned he couldn’t be right against the party. Nothing like that is on the cards here. That’s not the point. But the point is, if the vector of forces is such that the strategic line can’t be followed, as you laid it out so well, is there a sense in which you feel that you can’t be right against the party?

A very difficult question, because you have to take into account first what the party is. There are all kinds of factions or points of view or components in the party. You can be within the party taking almost any position!

But I meant this in terms the march that the leadership of the party is on, as the road is being made as you walk on it. If you were to come to feel that road was leading to a dead end or a labyrinth, could you feel you can’t be right against that?

I think there are, let’s say, certain lines. I only feel this, I cannot prove it. But there are some lines that cannot be crossed for me. It’s personal. And since I don’t know what these are exactly, I cannot lay out beforehand the conditions under which these lines become drawn and how they could not be crossed.

The line we are having right now I support, plus or minus the adjustments that have to be made along the way. But I support it. I support the cost of giving up more in the negotiations than I thought we would give. Nevertheless, one’s sense of what you could do, what you have to do, what you could not do, etc., changes every day.

So you cannot formulate an answer beforehand to the question. What operates at this level is how you feel your own responsibility, how you feel it in relation with how other comrades in the party are feeling it.

Personally, I have a kind of breathing space within the party. I have found myself at a place a bit beyond everyday problems or conflicts. Some may even say I am naive. I accept that. Sometimes I even say that naivety can be a political asset. I like to be naive in some respects. Still, I know there are lines that cannot be crossed for me. What I don’t know is how these lines will be drawn, given that the conjuncture is changing day by day. But I have a view of what has happened these three months. As for the next three months, I don’t know where I will find myself.

Join the task force inside the party to unleash the economy of needs?

Perhaps! But for the moment the future from this point of view is completely unknown to me, even in the sense of having an inkling of what the future will be like. The real problem right now, for this ministry, is that we cannot yet govern, because everything hangs on the negotiations, and even this ministry, which is not in the negotiations, cannot really start to function in a literal sense unless we have the minimal kind of money to just let things go on and start making the kind of reforms we were talking about before.

So it’s three months of freezing, as it were, the internal workings of the state, not really doing business as usual, not at all like that, but just letting some things go on because you cannot do otherwise, trying to stop other things because we can.

I’ll give you an example. We have European funding for development which amounts to a lot of money for us. What is going to happen with this money? So at the level of governing, we are very constrained. We have not yet started to really control the state.