The Making and Unmaking of Global Capitalism

The authors of The Making of Global Capitalism respond in the conclusion to our seminar on their book.

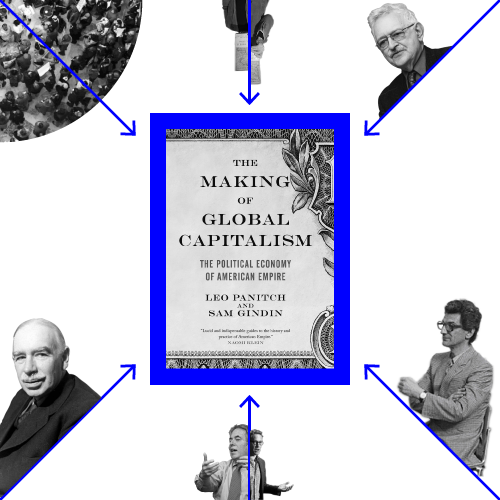

(Remeike Forbes / Jacobin)

In light of Jacobin’s emergence as an exciting site for rethinking Left interpretations of the world and new possibilities for radical change, we are especially grateful for this forum on our book. The comments that have been solicited are very generous, but they also raise important points of difference.

Göran Therborn challenges us to more precisely define and date global capitalism and suggests that doing this implies a deeper engagement with world systems theory. Though world systems theory is rich in so many ways, its 500-year sweep suffers from what we referred in an earlier article as the ‘myopia of the macro’ – it misses the unique specifics of capitalism as a social system. As we tried to make clear in the opening pages of the book, we do indeed see capitalist globalization as a long historical process but the instantiation of capitalist social relations had not, other than in the case of Britain, advanced very far until the second half of the 19th century. Furthermore, though capitalism exhibited an intrinsic dynamic towards expanding internationally, this process came across many barriers, including growing inter-imperial rivalries and spheres of influence. In fact, for most of the first half of the 20th century, with two world wars and communist revolution punctuated by the Great Depression’s interruption of international trade, a universal space for capitalist accumulation actually seemed impossible. It is in this context that we stress the qualitative changes that led to the realization of a global capitalism through a long process stretching from World War II to the beginning of the 21st century.

Therborn suggests that our concentration on the central role of the US in this process amounts to a narrative about ‘globalization in one country’. But we repeatedly emphasize that the initiative did not necessarily come solely from the US but also from state elites and capitalist classes who facilitated the making of global capitalism within their own societies via integration with the informal American empire (‘imperialism by invitation’). Henry Farrell, for his part, insists that the ‘the EU’s economic and monetary union was a product less of encouragement by the US hegemon than of European fears of what that hegemon implied for them’. But that is precisely our point: the new American empire involved sovereign states making their own decisions, but their options were nevertheless heavily structured by the American state and the choices made were generally consistent with the American project of making an open world capitalism.

Farrell argues as well that in emphasizing similarities, we understate the varieties of capitalism, and the tensions these produce. The very nature of a global capitalism that operates through sovereign states, each of which are affected by the balance of social forces within their own territory, necessarily implies variation. But to the take the strongest example, for all of Sweden’s status as an iconic welfare state, it has over the past 25 years experienced the greatest growth in inequality among all the OECD countries. The reality, as Greg Albo has put it, is increasingly that of ‘varieties of neoliberalism’. The very complexity of globalization can’t help but bring frictions of many kinds, but what is so remarkable is that, even with all the tensions that such a deep crises as the current one brings, we haven’t seen a retreat from free trade and free capital flows into national protectionisms. What is so striking is the effort that capitalist states have made to work together to reproduce global capitalism in this crisis, and their accession to the leading role of American state institutions in its continuing economic management.

It is, of course, entirely reasonable to want to hear more, as Nicole Aschoff does, about the connection between ‘the expansion of the US state’s “coercive apparatus” and the expansion of its ability to superintend the global economy’. We largely left aside the role of the US military and security apparatus since it has been so extensively dealt with by others. As the world’s dominant military power, the American state is burdened with keeping order in a chaotic world (much as, for example, the LAPD tries to do in south- central Los Angeles). To reduce this to serving the interests of particular American capitalists is far too narrow a conception of American empire. And to concentrate on American military interventions, or even American military bases around the world, is to miss the quotidian superintendence of global capitalism that institutions like the Treasury and Federal Reserve are engaged in.

Mike Beggs reinforces our argument in a very rich way by focussing on how the contemporary role of these US institutions was founded at Bretton Woods, and remained dependent on successful functioning of the US dollar international monetary regime that it put in place. He shows, as we do, that the US was itself subject to the discipline of financial markets even if it could modulate their application. This was so because in order for the dollar to retain its status and solidify the US as a safe haven for capital, the American state had to retain the confidence of external and domestic investors. This demanded vigilance about inflation, demonstrating the dynamic capacity to renew its competitiveness, and continuing to guarantee the sanctity of property rights (especially those of creditors). The crisis the Bretton Woods framework entered into by the 1960s was not about American decline. It was rather about the constraints the Bretton Woods framework placed on the American state in simultaneously dealing with domestic working class expectations and US global responsibilities. This was resolved by way of ending the gold standard and replacing it with an explosion of financial markets anchored in the dollar, as well as by disciplining labour in terms of both wages and acquiescence to management authority. The American state was subsequently provided with the ability to continue carrying out its global responsibilities while also renewing the domestic material base for doing so.

This has significant implications for the contrast Nicole Aschoff insightfully draws between our overall argument and Giovanni Arrighi’s. We learned much from Arrighi but his argument that the financialization of US capitalism replicates the decline of successive commercial empires over the past half-millennium missed (as with other World Systems theorists referred to earlier) the historically specific nature of finance in today’s capitalism. The point has often been made that US finance now plays a major role in integrating labour, giving consumer debt a unique historical weight in financial activities. But what also needs to be acknowledged is the key role financial markets play in greasing the wheels of international trade and global production networks. And given the global centrality of US financial markets (including the foundation that Treasury bond prices set for global interest rates), we certainly cannot read off American decline by pointing to the expansion of finance. And in this regard, the accumulation of dollar reserves by Asian central banks, combined with the new flow of capital into the US states is an indication, as we show, of the structural strength of US capitalism, not its weakness.

To argue that the growth of American finance has consolidated rather than diminished the American empire is not to deny new contradictions that envelop finance. But these do not revolve around conflicts between finance and industry; nor are they simply a response to irresolvable weaknesses in production. Rather, the contradiction lies in the fact that financial liberalization has been critical to capitalism’s dynamism yet that liberalization is inseparable from the financial sector’s extreme volatility. The unresolved dilemma for capital and states is finding a balance: how to limit the dysfunctional effects of financial volatility without limiting finance’s functional contributions to global capital accumulation, especially since one of these functional contributions, as we see in the role finance plays in enforcing austerity policies in the current crisis, is the disciplining of labour.

In light of the influence Dick Bryan and Mike Rafferty have had on our understanding of global finance, we are especially gratified to see they have been persuaded by our ‘framing of US empire’. Yet insofar as our analysis still seems ‘surprisingly nation centered’ to Bryan and Rafferty, this strikes us as reflecting a rather undialectical appreciation of the extent to which the global is necessarily embedded in the national. There is no global space except within nations themselves, and even while classes internationalize they remain rooted in nation states. Our central concept of the internationalization of the state is precisely designed to capture this. States – some much more than others for reasons that need careful historical investigation – come to take responsibility for extending capital accumulation and capitalist social relations, and for superintending and reproducing global capitalism, in and through other nation states as well as within their own territories and social formations. As much as we appreciate Bryan and Rafferty’s work on the structural power of financial markets, we insist that this power cannot be properly understood apart from how these markets are anchored in the American state, not only via its particular responsibility for the American dollar and its relationship to dominant financial institutions, but also via the central roles the Treasury and Federal Reserve play in making the rules for global financial markets.

It was from Bryan and Rafferty, above all, that we came to understand properly the role that derivatives play, not only in hedging risks associated with multiple exchange rates between national currencies, but in making values commensurate across space and time – that is, in establishing the price evaluations essential to corporate decision-making in a world with new uncertainties. In light of this, we are rather surprised that they suggest we don’t address how finance changes qualitatively in relation to the ‘momentum of accumulation’. Indeed, our book not only addresses qualitative changes in finance such as derivatives, but also the qualitative changes that the incorporation of working classes through credit, pensions, mortgages and so on entails. Moreover, we stressthe qualitative changes that take place in state financial institutions so as to superintend the changing relation of financial markets to the momentum of accumulation. We show how this takes place via the emergence of new state institutions (such as the CFTC) to facilitate financial innovation (such as derivatives). And we showhow the Treasury and Federal Reserve themselves were changed in qualitative ways as they practiced ‘failure containment’ in the face of financial volatility and crisis (the Fed’s practice of quantitative easing has been called ‘the greatest experiment in the history of central banking’.) As well, the book does extensively analyze (as Bryan and Rafferty ask us to do) how the crisis created ‘new challenges for the US state to reconcile domestic with global agendas’. To take just one example, we show that from the summer of 2007 on the Federal Reserve, playing the role of global central bank, extended loans to private foreign banks while concealing this from public purview, and then moved to dollar swaps with other central banks precisely to avoid an uproar from Congress over ‘bailing out’ foreign banks.

Martijn Konings’ understanding of the tensions involved in the US exercising responsibilities for reproducing global capitalism while remaining a distinctively American state has always been a profound one, as his comments here once again demonstrate. He properly suggests that more work is needed to understand, not only the paradoxical complexity of the relation between the state and economy, but also the complex dynamics of how state secure democratic legitimation. We agree with this, including the stress he puts on pragmatic state usages of a distinctively American populist political style to this end. While we would indeed insist on the extent to which ‘elites are able to sideline or bypass democratic processes’, we also think it is very important to see how they go about securing democratic legitimation. This is why we paid such attention to the Treasury’s extensive PR campaign across the country to the end of getting the Bretton Woods Agreement through Congress, although we would still insist that the determining factor in effecting this was the compromise the Treasury made with Wall Street. And while we would agree that there is ‘no sure-fire way of governing the republican imaginary and the popular sentiment it evokes’ in American political discourse, it is nevertheless remarkable how successfully Congressional opposition to the Fed or Treasury exercising their global responsibilities has been overcome. This proved once again to be the case on the ‘debt ceiling’ issue that Konings points to.

Konings’ comment also raises a crucial political question for the Left, concerning the degree to which much of its own discourse on both empire and neoliberalism heretofore has actually been counter-productive. This applies to much naive rhetoric around deregulation, which simply reverses misleading shibboleths about ‘states versus markets’, and it applies all the more to easy claims about American economic decline. Indeed, our book was in large part motivated by our concern to provide some correctives to all this. Progressives seem to believe that to shout American decline from the rooftops delegitimates the system. But as we’ve often seen, aside from the mass political fear rather than mass political courage the rhetoric of decline may generate, it may also actually promote ambitions to fix the system and return to a state of affairs that the Left used to itself criticize but is now engaged in making look relatively benign. And as Konings points out, this melds with a long tradition of declinist rhetoric on the right of the political spectrum, which tends to emphasize divergence from the ‘true’ American path laid out in the Constitution, and uses a call to make America ‘whole’ or ‘great’ again to mobilize for popular sacrifices to strengthen American capitalism and shut down external threats. Konings is surely also right to emphasize the need to take much more seriously the material foundations of the ideological integration of the working class, and not reduce it to right wing mumbo-jumbo to be corrected by dire predictions or moral rectitude, media manipulation, or simple working class confusions about self-interest. And he is also right to make the link between populist support for austerity as expressing a sentiment that understands the need for collective investment in the future – a sentiment socialists would themselves have to draw on in the face of the disruptions and sacrifices any real move towards transformative social change would involve.

Given our long-standing concern with exactly these types of strategic questions, we are puzzled by Elizabeth Humphrys’ argument that our approach to the theory of the state rules out any serious consideration of such transformation. In fact, our approach starts with the understanding that the economic and political are part of a capitalist totality founded on competitive, exploitative and conflictual class relations – that is why we studiously avoid the term ‘separation’ in favour of ‘differentiation’ between state and economy. But the trouble with the familiar formula Humphrys advances, which involves ‘deriving’ state theory ‘from the commodity form and the capital relation’, is precisely that it fails to take seriously the differentiation between the political and the economic. Nor does it take seriously the need to analyse carefully the long historical process through which this took place, and how distinct sets of state institutions historically developed with specific roles and capacities. In this regard, far from ‘reading off the strength of the working class from the fact that Keynesian policies were in place’, or stressing that state institutions are ‘relatively insulated from the pressure of the balance of class forces outside the state’, our book goes to great length to do the opposite, detailing the ebb and flow of workers organization and struggles from the 1930s to the 1980s and beyond.

The derivation approach to state theory also leads to an abstract approach to a strategy for transformative class politics. The issue, of course, is not whether or not class struggles outside the state are important. Such struggles are obviously absolutely fundamental to any radical project. Nor is the issue simply taking over a capitalist state and administering it more progressively. By showing concretely how state institutions actually function to promote, manage and reproduce capitalism, we believe we contribute to a politics that is strategically sensitive to the challenge of developing working class capacities for transforming the state. To make a case for turning finance into a public utility as a crucial element in democratic economic planning has the same strategic status as the call by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto for ‘centralizing credit in the hands of the state’: it is oriented to contributing to developing the transformative ambitions and capacities of working classes. Of course, as was made clear in the Manifesto, this cannot be effected except ‘by means of measures, therefore, which appear economically insufficient and untenable, but which, in the course of the movement, outstrip themselves, necessitate further inroads upon the old social order, and are unavoidable as a means of entirely revolutionising the mode of production.’ Without drawing attention to how the state needs to be transformed so as to enhance and support the collective capacities to transform everyday economic and social life, we are left with heroic gestures that are simply not up to the task of removing the barriers to a new world. Addressing the need to socialize and democratize finance, which cannot be achieved without taking state power and radically transforming the state apparatuses, is so central both because finance represents such a powerful component of the capitalist class – challenging it is basic to ever challenging capitalist power – and because the very process of raising questions about finance opens broader democratic questions about capitalist societies. This, above all, leads directly to the question of what we would do with the surplus if we controlled it and so pushes us to even bigger questions about how we organize our economy and lives.

This relates to how we might respond in the limited space available here to Bryan and Rafferty’s challenge to elaborate our thoughts on the working class today as an agent of change. We see the past three decades as involving not only a profound defeat of the working class, but as a radical reshaping of the class both ideologically and materially. Finance has clearly been a crucial part of this as workers increasingly became prominent savers, investors and debtors with all this means for individualization, the dependence on financial markets for returns and asset growth, the identification of interests, and the atrophy of collective demands and collective forms of struggle. But as important as finance has been to this process, we would emphasize its location within the larger context of capitalist development: the implications of the global spread of capitalism including freer trade and the accelerated growth of MNCs and integrated networks of production; the restructuring of production inside workplaces, across companies, across sectors, and geographically within countries; the uneven development that accompanies all this and what it means for ‘cultures of solidarity’; the legislative attacks on labour unions and the politics of austerity; etc. Some have gone so far as to argue that workers’ integration into financial circuits marginalizes the salience of class but we would in contrast argue that the ever-deepening commodification of labour, including via its incorporation into the circuits of finance, makes the strategic question of how to engage as socialists in the remaking of working classes in the 21st century more relevant than ever. The integration of workers into finance does indeed mean that there is a greater material basis now for increasing workers’ consciousness of their ‘subjectivities across the circuits of capital’, as Brian and Rafferty put it. And the importance of socialists addressing the need for turning finance into a public utility is to contribute to this by showing its is a precondition for the economic planning needed if collective goods and services are ever to displace individualized consumption.

This in turn relates to the more general question about the political implications of our book. We see our book as providing a sober grounding for confronting what we must do if we want to bring about new possibilities. Our book argues that capitalism will not be brought to its needs by the external conflicts of inter-imperial rivalry (capitalism is too integrated across states), nor from internal divisions among fractions of capital (their mutual dependence is too strong), nor from mechanical laws of falling profits (as long as we continue to accept its impositions, capitalism is likely to find ways to renew itself). It is out of a renewal of class struggles within each state – which will necessarily have international implications – that the unmaking capitalism can come about.

As we suggest in our conclusion, the widespread conviction in the twentieth century that ‘global socialism would effectively constitute the alternative to global capitalism’ has passed away. It did so not only due to the successes of the latter but also due to the many limitations of social democratic and communist political institutions and their associated trade unions. While a good many of the reforms they sponsored are still in place, they have lost any association with the notion of a socialist alternative, and at best only provide means for people to access a certain basic standard of living within capitalism. It is in this sense that we say that ‘individualized consumerism rather than collective services and a democratized state and economy became the main legacy of working class struggles in the twentieth century.’

Today, socialists are virtually starting over. We need new political organizations to overcome fatalism, revive hope, engage in honest reassessment of the limits of current class struggles, and through radical education encourage people to talk about socialism once again. In this regards, we especially note Jacobin’s constructive commitment to ‘identifying capitalism as a social system that benefits a minority, and openly organizing in civil society to challenge it.’ And as the editorial in the Spring 2013 issue goes on to say, this especially means building new socialist ‘institutions and organs of class power and presenting real alternatives’.