Strike for America

For every Facebook share this piece gets, Jacobin Press will donate $1 to the CTU strike fund. We're broke so our contribution will cap out at $750.

In 1991, Tom Geoghegan subtitled his memoir of life as a labor lawyer “trying to be for labor when it’s flat on its back.” Two decades later, the image needs some updating. It’s only accurate if you picture labor flat on its back on, say, a stainless steel emergency room operating table, its heartbeat heard only occasionally and faintly. Future prospects appear grim, but the doctor doesn’t have the heart to tell the family. They’re still in denial.

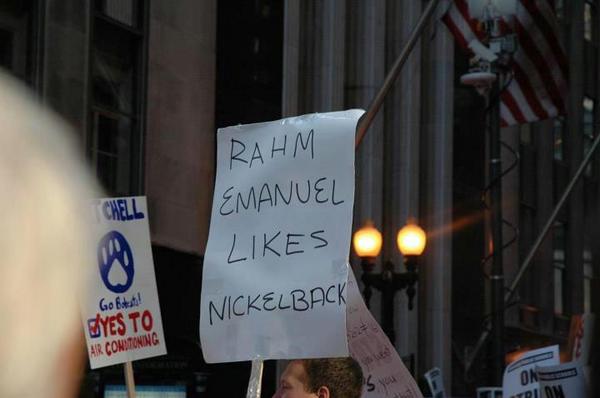

At least, that picture seems fairly accurate on bad days working in the labor movement, which come more often than the good. But there’s some hope now in Chicago. The teachers are on strike, kicking ass, and taking names — specifically Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s, frequently in vain.

At a time when the unspiring labor movement has become weakened almost into irrelevance and the Democratic Party continues its rightward drift into an open party of austerity, the CTU is taking militant action through a tightly-organized membership and a rank-and-file-led leadership in the face of legal barriers previously deemed insurmountable against a Democratic mayor pushing neoliberal education reform.

He’s also just a really, really big dick.

It’s almost enough to make you think labor might be able to hoist itself up off that table before the monitor completely flatlines.

This fight has been a long time coming. Bill Barclay lists three crucial factors in the lead-up to the strike, including the imposition of a neoliberal education reform model, begun long before Emanuel took power in the city but embraced exuberantly by him; legislative attacks on the CTU designed to strip the union of power to clear the way for such reforms, led by corporate-backed organizations like Stand for Children; and the election of new, militant union leadership.

The first has entailed an aggressive agenda of privatization, expansion of charter schools, school closures, expansion of standardized testing, and other reforms pushed by those who stand to cash in by stripping all that’s public from our education system. Nationally, teachers unions are seen as the primary obstacle to this agenda — which is why corporate education reform groups have aggressively pushed the second, like SB7, the bill that passed the Illinois state legislature last year explicitly designed to make a teachers strike impossible.

The third can be credited with channeling widespread parent and teacher anger into the political form of a strike — one with organizing capabilities to overcome the new legal barriers. The Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE), a reform CTU leadership slate, took over the union in 2010, explicitly campaigning on taking a more militant and grassroots stance against neoliberal reform. The city has become ground zero for free market educational experiments — and for pushback from parent and teachers. Conditions were ripe for the rise of leadership that would push the union’s agenda to the left.

True to their campaign promises, CORE’s agenda has focused on much more than teachers’ salaries and benefits. Even now, when the CTU can only legally strike over wages, benefits, and some parts of teacher evaluations, union leadership continues to emphasize their fight is about a holistic vision for education that unequivocally opposes neoliberal reforms.

At the union’s press conference on Sunday night announcing the strike, reporters asked CTU President Karen Lewis what the primary two or three issues that had become sticking points in CPS negotiations were. She replied that all issues, from compensation to smaller class sizes to the increasing reliance upon standardized testing to understaffing of positions dealing with “wraparound services,” like social workers and clinicians, were causing the impasse.

And in response to SB7, the union engaged in an incredible mobilization and education effort of its membership. The law changed the requirements for a strike vote from a simple majority of voting members casting ballots in favor of a strike to 75 percent of the entire bargaining unit of over 26,000 voting to strike, with abstentions counting as “no” votes — a feat which the bill’s backers regarded as impossible. The CTU then proceeded to achieve the impossible, authorizing the strike with a 90 percent yes vote of all members and 98 percent yes among those who voted.

Rather than squeaking past a legally-required simple majority to authorize a strike, with a large portion of the membership opposed or unenthused about walking off the job, the union now has a totally mobilized, fired-up membership, repeatedly turning out en masse in the streets.

A broad vision of social movement unionism coupled with comprehensive rank-and-file mobilization and education: this is the kind of labor movement many on the left have long insisted unions need to pursue if they are going be relevant to the overwhelming majority of workers in the U.S. who don’t belong to unions and are increasingly hoodwinked into believing that union members’ access to some bare-bones standards of decent lives (e.g. pensions and less-than-barbaric health care) can only come at their own expense. Stephen Lerner called it “connecting collective bargaining to the common good.”

In CTU’s case, it seems to be paying off. Community groups have rallied strongly around the union, helping prevent the city from framing the teachers’ fight to parents as detrimental to students.

The union, once isolated in Chicago’s labor movement, now has strong ties to many other unions who have repeatedly mobilized members in support of the teachers. The union has successfully positioned themselves as a true social movement with a strong concern for the broader good rather than a narrow-minded self-interest group.

It’s almost like the CTU actually believes in all that “solidarity” shit.

The CTU called for pickets at local schools to begin at 6:30 AM Monday. Lacking the discipline instilled by more demanding professions (like, say, teaching), I couldn’t even drag myself out of bed until that time. Thirty seconds into my bleary-eyed bike commute downtown, I encountered my first group of picketers a few blocks southwest of me. I would’ve forgotten there was an elementary school so close to me, but the sounds of teachers chanting and the sight of their bright red union T-shirts made them unmistakable.

Somehow, it hadn’t occurred to me that a public school teachers’ walk-off would entail pickets in front of every public school, which would mean a blanketing of the city in striking educators. The six-mile bike ride from my far North Side apartment to the Board of Education downtown was surreal: I saw so many picket lines of red-clad teachers while heading south that, in my sleep-deprived state, I lost count. It felt like Chicago belonged to the teachers.

I stopped at the second picket I saw, with about forty teachers five blocks or so from the mayor’s home, to snap a picture. As I pulled out my phone, the slim middle-aged African American teacher in charge of the bullhorn started chanting, “We’re going to Rahm’s house!” He stopped after chanting it a few times, giggling, but an early-forties white woman who looked stunningly like my ninth grade American History teacher wasn’t laughing.

“No, seriously. It’s right over there,” she yelled out, pointing west towards Emanuel’s residence on Hermitage Avenue. “We should go.”

It’s not easy to get teachers pissed enough to want to march on a mayor’s house — they’re usually deescalating conflicts. But Rahm Emanuel has deftly accomplished this, mostly by his unflagging consistency in telling teachers to, in Rick Perlstein’s words, “eat shit.”

He brazenly canceled a contractually-obligated 4 percent cost of living raise for teachers last year; he pushed hard for a 20 percent longer school day while offering a 2 percent pay increase (a fight he eventually lost); he has unabashedly denigrated teachers, accusing them of not caring about the well-being of their students. Despite campaigning on promises of reform, he has gone full-steam ahead on the city’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) system, which diverts huge amounts of tax dollars from public institutions like schools and libraries and funnels them to wealthy corporations.

Emanuel would clearly love nothing more than to break the back of the CTU in this fight, to have his own PATCO or Wisconsin 2011 moment. (Incidentally, when Gov. Scott Walker spoke to a small breakfast of wealthy donors in Chicago earlier this year, he praised Emanuel’s hardline stance against unions.) Perhaps even more than other Democratic austerians like Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York, Emanuel almost visibly relishes in sticking it to the working class — and, for some reason, to teachers in particular.

Which might have something to do with why so many Chicago teachers voted overwhelmingly to strike. And why anti-Rahm chants were thundering throughout downtown for hours yesterday. And why such a massive cross-section of Chicago has joined in the struggle against the mayor. His hardline stance against the CTU has driven scores of average citizens and apathetic into the union’s camp — and thus into the streets, onto the picket line, and decidedly on the left side of the biggest labor fight the city has seen in decades.

The strike’s first day ended with an absurdly massive rally and march downtown to the Board of Education and City. I arrived as the march was already underway, entering somewhere in the middle of the crowd; I spent about fifteen minutes wading through the crush of people trying to get to the front, but never found it. I jumped up on a concrete planter to try to see the march’s end; never saw that, either.

The rally took a long time to wind down, protesters clearly enjoying the real sense of ownership they had over the city. We gradually dispersed from Daley Plaza, where a Turkish festival was taking place. Two Turkish tourists with shaky English abilities approached my friend seated next to me on a concrete bench, a young radical wearing a red “Solidarity with the Chicago Teachers Union” T-shirt. They pointed at the shirt — what did it mean?

My friend first read it, then tried to explain, but drew only blank stares. He tried to talk about the strike, which they seemed to tenuously understand. Then one asked, “You like Democrats? Obama?”

I turned to face my friend. He paused for a moment, carefully parsing his thoughts, then stood up.

“Romney, here,” he stated, holding his hand palm-down, parallel to the ground, below his knees. “Democrats, Obama,” he continued, raising his hand to his bellybutton, “here.”

“Teachers on strike,” he said finally, raising his hand above his head, as high as he could stretch, “here.”

The two nodded slowly. This, they understood.